The Truth of Lockdown, and its Escape

Daniel Defoe and John Donne’s alternative languages of disease and isolation—and their meaning now.

The world is yet to imagine Covid. We have no visions of the lockdown, no language even, beyond the official vocabulary that dominates all talk of the pandemic. It has been difficult, of course, to see beyond the window from our various vantages of confinement and sequestration. This makes a Covid imagination all the more urgent, however. As we begin to emerge from our rooms, it’s worth imagining what our confinement meant, and how it can be cast off.

Looking back to a period when the language of contagion was more fluid, there are two early modern texts in particular that urge us to reimagine the impact of disease on our social relations. Daniel Defoe’s part-fictional account of the 1665 London plague, Journal of the Plague Year, offers an account of lockdown that presages our own regime, but with a frank and brutal class consciousness that is sorely lacking today. John Donne’s 1624 Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, quite differently, is a vision of transcendent human connection—an attempt to rescue our subjectivity from the atomized, sequestered social life of illness.

Marx spoke of a future world market as manifesting “the connection of the individual with all, but at the same time the independence of this connection from the individual.” The more connected people are, the less aware of it they become, as all relations are reduced to what is fungible, abstract, equivalent in them. Most people already knew twenty-first century globalization as atomization, and in this sense the lockdowns have been an intensification rather than a break. Intensity matters in itself, however, and the way Defoe and Donne, in their very different ways, made such “connections,” and connected them to illness, is instructive.

Our current, official imaginary conceives of Covid as a natural disaster that compels us into emergency security measures of social sequestration. Defoe and Donne provide us with something different.

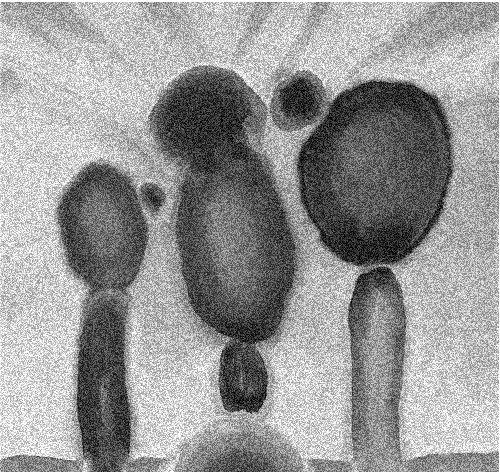

Their texts appear shortly after contagion became established as an English word. Though there is still no theory of germs in this period, there is a sense of what today goes by the name of “community transmission.” Contagion has the same Latin root as contiguous, ultimately tracing back to tangere, to touch. Unlike the earlier, more figurative and moralistic infection (literally, stain) or the pseudoscientific miasma (bad vapor from the earth), contagion invokes touching, proximity, a chain of contact, transmission from person to person. The word contagion becomes current, that is, because people are starting to think increasingly about how they relate to other people in times of illness, rather than just about a punishment from God or a cursed land.

A Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722, presents a similar emergency regime to Covid’s planetary lockdown. It gives us a fresh look at this regime, however, because of how vividly it expresses its priorities. Despite his time’s very different understanding of infectious disease, Defoe describes the same preventative measures we see today (mainly locking people in their houses). Just as Defoe is now seen as the first writer of the British Empire, so too he predicted the Lockdown State.

Defoe is alive to the class divisions that accompany plague. Contrary to the popular wisdom that epidemics make no distinction between rich and poor, Defoe recognizes the unequal distribution of misery. However, he roots this inequality in a sense of the different moral qualities of rich and poor. The poor suffer worse partly because they are poor, but mainly because they are naturally less human:

It must be confessed that though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; I must call it so, for it was founded neither on religion nor prudence; scarce did they use any caution, but ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous. Such was that of tending the sick, watching houses shut up, carrying infected persons to the pest-house, and, which was still worse, carrying the dead away to their graves.

Though the inequality must be confessed, it is nonetheless excused as the fault of the poor themselves. Rather than a consequence of their poverty, the poor’s heavier burden of plague is a result of their own carelessness. Defoe’s judgement echoes through the centuries to today’s liberal shock at those carrying on with their business, sometimes unmasked.

This conception of poverty and disease informs Defoe’s moral sense of prevention, which is likewise close to ours today. That is, Defoe frames the plague as a matter of security. The maintenance of existing property relations is the absolute priority. He worries about what he calls “the mob”:

But the vigilance of the Lord Mayor and such magistrates as could be had prevented this [mob]; and they did it by the most kind and gentle methods they could think of…particularly that employment of watching houses that were infected and shut up. And as the number of these were very great, this gave opportunity to employ a very great number of poor men at a time.

The women and servants that were turned off from their places were likewise employed as nurses to tend the sick in all places, and this took off a very great number of them.

And, which though a melancholy article in itself, yet was a deliverance in its kind: namely, the plague, which raged in a dreadful manner from the middle of August to the middle of October, carried off in that time thirty or forty thousand of these very people which, had they been left, would certainly have been an insufferable burden by their poverty; that is to say, the whole city could not have supported the expense of them, or have provided food for them; and they would in time have been even driven to the necessity of plundering either the city itself or the country adjacent, to have subsisted themselves, which would first or last have put the whole nation, as well as the city, into the utmost terror and confusion.

It was observable, then, that this calamity of the people made them very humble…

The “kind and gentle methods” of the ruling powers lead to the deaths of thousands of people, but this is a blessing in disguise, since it both purges the city of its poor and disciplines any survivors. What is shown here, nakedly, is that it is not saving lives that is the priority of such preventative measures, but the shoring up of the State and the property relations it protects. Public health under such a regime is not an end in itself, but a means to security; when this security is directly threatened, the latter trumps the former in the most barbaric fashion.

We have not been alive to the class divisions of Covid. Sequestered, we have had little space to share, encounter or conceptualize them. There are discrete facts: that the working poor have died more from Covid, over 100 per cent more even at the national level; that prolonged lockdowns force the poorest to go without a wage; that wage stagnation is predicted for years after lockdowns are lifted; that the privatization of life most impacts those with the least private assets; that billionaires everywhere have increased their cut of national wealth, doubling it in India, China and Brazil. At present, these glimpses are the best we have.

For Defoe, London was a series of direct encounters with poverty. Such encounters with the social relations in which we live are increasingly what contemporary capitalism occludes, and what lockdowns occlude especially. Defoe was faced with these relations so clearly, and felt them so deeply, that he was compelled to justify their brutal obliteration. In his imagination, mob rule and rioting lie at the other side of plague. A lockdown erasing inconvenient social relations, therefore, is preferable to a political breakdown: the poor must die. We obviously don’t want Defoe’s solution, but we could certainly use some of his clarity.

Covid’s social relations, described above, are either dismissed as unworthy of consideration at all, or excused as sins of omission. With the first, like all securitized crises, politics is the first to go. Only a pedant would luxuriate in such matters when the social order itself is under threat. With the second, because all political effects are framed as a consequence of doing nothing, the great imperative of social distancing, there is no political responsibility to be taken. Like Covid, lockdown’s effects are conveniently natural. Defoe, repulsive though his politics are, at least takes this responsibility, or is at least honest about his dereliction of it.

We get quite a different community of disease in John Donne, primarily known as a love poet and later as Dean of St. Paul’s. His Devotions come about a hundred years earlier than the Journal, when the language of disease is even more fluid. Donne wrote his suite of religious meditations during or shortly after a life-threatening illness. It takes us through the stages of an illness, at the beginning of which Donne assumes he’s dying, then gets worse and worse before improving and coming out alive.

The most famous moment of the text is Donne’s rumination on a church bell. Donne is laid up in bed: he’s isolated, he’s lonely, but he hears through the window the sound of the church bell tolling. Conventionally, this signifies the death of a parishioner, and Donne thinks on this. He remembers that once the bell tolled when no one was sick, and the next day someone fell off the steeple, so he wonders if the bell is tolling prophetically for his death. His thinking here prefigures the more general conclusion he will draw about human dependency:

We scarce hear of any man preferred, but we think of ourselves that we might very well have been that man; why might not I have been that man that is carried to his grave now? Could I fit myself to stand or sit in any man’s place, and not to lie in any man’s grave? I may lack much of the good parts of the meanest, but I lack nothing of the mortality of the weakest; they may have acquired better abilities than I, but I was born to as many infirmities as they.

Donne here identifies with another man he does not know and cannot see. The relation is of necessity imaginative, abstract, because Donne is bed-bound. It is, though, real and felt because Donne takes it absolutely to heart. Though he can’t directly see this relation, the absolute equality of mortality and Donne’s own vulnerability brings it home. The key to all of it, of course, is that Donne has a powerful sense, in the holy catholic communion of the Church, of community.

Donne goes on to give us some of the most famous sentences of seventeenth century prose:

Perchance he for whom this belltolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me, and see my state, may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that. The church is Catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that body which is my head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member. And when she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author, and is one volume… As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness… The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God… No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Like the bells, whose sounds spread from a single point, Donne’s metaphor expands to encompass the universe. Donne’s rejection of island metaphors is a beautiful commitment to our non-identity with ourselves, for how we find ourselves in others, and of how the single is always many, the many single. Defoe’s anti-social praise of deadly jobs for the poor is interested primarily in sundering social relations; Donne seeks to imagine and assert them.

Illness for Donne had a fundamentally social character because he partly imagined it as a manifestation of sin, which connected it to the Church. We need not embrace this particular disreputable idea, though, because there are many others in the text that similarly plug individual illness, where one often feels most alone, into the social complex. One is the figure of the doctor, one so surprisingly absent from the Covid imaginary.

Donne says a simple but beautiful thing about doctors: ‘We have the physician, but we are not the physician’. He continues:

I cannot rise out of my bed till the physician enable me, nay, I cannot tell that I am able to rise till he tell me so. I do nothing, I know nothing of myself; how little and how impotent a piece of the world is any man alone? And how much less a piece of himself is that man?… A man that is pressed to death, and might be eased by more weights, cannot lay those more weights upon himself: he can sin alone, and suffer alone, but not repent, not be absolved, without another.

Under Covid, we are told inaction is action, that our social duty is to do nothing, that we care best for each other in turning away. Doctors have no place in such a regime, and so ours is a language of law. Donne, on the other hand, presents remedy as a dependence, a coming together, a caretaking; and it’s the physician, the figure of our reliance on another at its most absolute, an embarrassment to the self-reliant subject, that he embraces.

Defoe seeks to dispose of social relations that are clear to him but have become inconvenient. Donne tries to imagine and make vivid relations that have become difficult to see. Defoe, chillingly, gives us the cold reality; Donne a vision of warmth. Since Covid has distanced us from our relations, Defoe’s clarity is in itself salutary, however ultimately disavowed. Donne gives us something different: an absolute avowal. We are slipping away from each other: even as lockdowns are lifted, many are reluctant to go back out into a such a cold and hostile world. As an antidote, Donne presents a glimpse of social relations that can be re-felt, reimagined and cared about, even when we feel most isolated and delirious.

■

Ben Hickman lectures on poetry in England, at the University of Kent.