The Utility of Utilities

Climate activists are no fans of electric utilities. But the market-based alternatives that they often prefer—for rolling out renewable technologies faster than utilities—will not deliver infrastructural change at the scale we need.

Taller than the Washington Monument, planted in ocean-floor monopile foundations weighing as much as four 747s, heaving blades the length of a football field, offshore wind turbines were meant to be the new American clean energy juggernauts.

Generating power at a larger scale and more frequently than onshore wind turbines, though still intermittently, offshore wind has been central to the decarbonization goals of President Biden and of Atlantic blue states. As of this past January, decades behind its European counterparts, the American offshore wind industry has two turbines, off two coasts, finally delivering power.

But last fall, the future of this focal point of the energy transition began tumbling into a political-economic crisis. Post-Covid supply chain bottlenecks and rising inflation led to escalating losses and plummeting share prices for German wind turbine manufacturer Siemens. Flagship offshore projects were canceled in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Their total power capacity amounts to about one-fifth of Biden’s goal for offshore wind supply by 2030, the delays all but guaranteeing a miss.

Each canceled project was undertaken with—and financially completely dependent upon—state-negotiated contracts in state-designed competitive auction processes to purchase “renewable” certificates from competitive developers. The power markets aren’t enough; developers of these immensely capital-intensive projects also need subsidies on top. It’s a common scenario for all renewable energy procurement, not just offshore wind, in blue states in particular.

Meanwhile, one massive 176-turbine project off the coast of Virginia is going forward without a hitch. It is owned and managed not by a competitive developer, but by the vertically integrated electric utility Dominion Energy. As a utility, they are afforded economies of scale and efficiencies in system planning. Dominion’s project is larger than the others, and while other projects are lacking in ships to install turbines (one example of the “supply chain problems” plaguing the industry), Dominion is simply building its own.

As a regulated public utility, E&E News explains, Dominion “uniquely enjoys” an investment model unavailable to those capitalists only seeking to develop wind energy alone: thanks to its regulated utility status, “its investments are paid for by electric consumers, with utility regulators approving a return on the investment as profit.” That older model lies in stark contrast to one in which increasingly bespoke markets, price signals, financial instruments, and auction processes, designed in tandem with state policies, lure capitalists without the burden of serving customers.

Newfangled markets and competition versus old-fashioned utilities. When it comes to building tomorrow’s clean energy infrastructure, it’s hard to find anyone left of center arguing in favor of the latter arrangement. That is, except for some of the labor unions representing the energy workforce.

The reality of climate change presents a need to develop clean energy. To decarbonize the whole economy, state-of-the-art modeling from Princeton suggests we’ll need to triple or quadruple electricity production by 2050. This entails not just some wind turbines here and solar panels there but a nationwide remaking of the industrial landscape. What if that older utility model offers greater potential to build the clean energy infrastructure we need?

Public Utility as Growth Engine

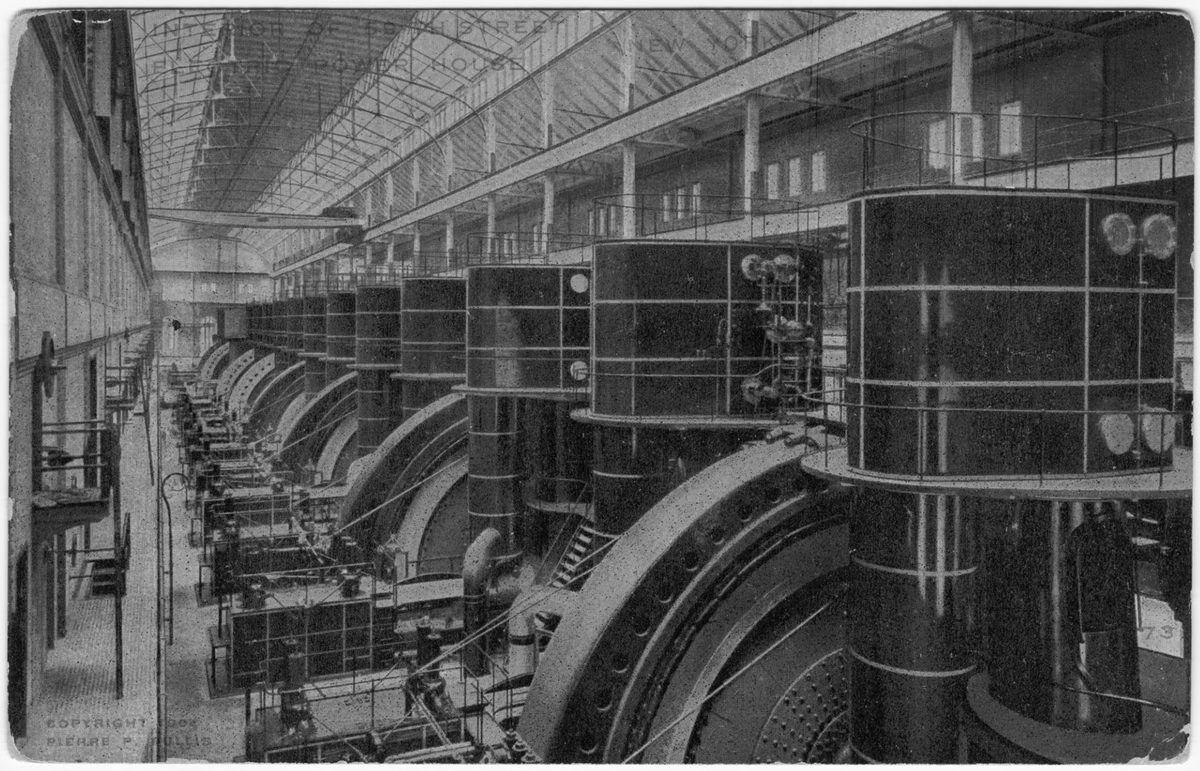

In the early twentieth century, electricity service providers competed with one another for customers, installing their own wire networks across cities to reach them. Apart from costly duplicated networks, this posed a problem for financing growth. Just like today, the electric power sector was then one of the most capital-intensive industries.

To solve the problem—and to ward off the threat of public takeover by socialists, a far stronger threat than today—electric power titan Samuel Insull steered the nascent industry toward a model of state-regulated monopoly service, not unlike natural gas and railroads. With that institutional arrangement came a long-term captive customer base and easier appeals to banks for the capital needed to reach economies of scale. The fetters on growth were removed.

Electricity service thus became a public utility nationwide. According to law professor William Boyd, the concept was established by early twentieth-century Progressive lawyers and technocrats—essentially, wonks—as an institutional protection of “a common, collective enterprise… too important to be left exclusively to market forces.” In exchange for their monopolies and guaranteed returns on investment, electric service providers would have to allow state regulators to crack open their books and approve revenues and expenses to ensure fair prices for consumers.

The electric utilities—henceforth simply “utilities”—grew into behemoths in wave after wave of consolidation, most famously by Insull, as nationwide holding companies. Three-quarters of all power resources were owned by nine holding companies, including one controlled by J. P. Morgan. Eventually, thanks to their immense wealth, political influence, sprawling propaganda machine, and complicated organization that evaded (or bought out) regulators, holding companies became the capitalist villains par excellence during the Great Depression. In 1928 the Federal Trade Commission launched a seven-year investigation into holding companies’ control of the utilities industry, culminating in the Public Utilities Holding Company Act. And in 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned for President railing against this Power Trust, “the Ishmaels and the Insulls, whose hand is against everyman's.”

For all its faults in the presence of weak regulation, though, the utility model worked: the growth of electricity infrastructure was explosive, if uneven. Profits were leashed not to sales per se but to capital investments, so new customers were sought, and new demand was developed in order to justify those investments to regulators. Unceasing orders for new power plants helped to finance manufacturer improvements in the ever-larger generators.

As historian Richard F. Hirsh explains in Power Loss, over the first half of the twentieth century, “productivity jumped… [at] a rate higher than that seen in any other sector of the private domestic economy.” Residential power prices fell precipitously. As a result, “electricity consumption bounded upward at a 12 percent annual growth rate from 1900 to 1920 and at a 7 percent average annual rate from 1920 to 1973.” But from 1990 to 2022, the average annual growth rate was only 1 percent.

Up until the 1970s, utilities handily met the escalating electrical needs of a rapidly growing economy. Insull and the Progressives—yin and yang—were onto something.

The Case Against Utilities

The basic “grow and build” strategy of utilities is often denounced for being environmentally wasteful and economically inefficient. But in today’s context, don’t we precisely need to rapidly “grow and build” clean energy? To understand the hostility, we need to return to the historical context of an often compelling political and public backlash toward the utility model that reached a fever pitch in the 1970s.

By the end of the 1960s, the forces of electrical production by utilities had more or less ground to a halt. Manufacturers seemed to hit technical limits on generator efficiency, and their newer, larger, less refined generators broke down more often, leading to pervasive reliability problems for utilities. Summer brownouts struck the Northeast in the late 1960s when hot weather strained the grid in the presence of such faults.

The 1970s energy crisis, culminating in the 1973 oil embargo, dealt the killing blow. Fuel shortages and skyrocketing power prices led to factory closures, unemployment, pricier consumer goods, lines at gas stations, and canceled vacations. Homes, schools, and workplaces were either uncomfortably cold or uncomfortably hot.

Meanwhile, new political shifts like the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 solidified growing concern with the impacts of the energy system on nature. Public confidence in the utilities industry fell throughout the decade; in one nationwide annual survey about the energy crisis, the share of respondents identifying utilities as deserving “major blame” doubled from 1974 to 1977. This turn against utilities complicated the case for state regulators to approve their construction programs for nuclear power plants, leading to many cancellations—a kneecapping of long-term clean energy infrastructure that we’re still feeling today.

Between the energy crisis and the rising environmental movement, the growth strategy embodied in the utility model started to seem less like an engine and more like a ticking time bomb. Seminal environmental works like The Population Bomb, The Limits to Growth, and Small is Beautiful validated the public’s kitchen-table problems during the energy crisis while promising that modern life could coexist with nature, not just destroy it. Conservation and decentralized renewable energy, rather than centralized and wasteful fossil-fueled energy, would be essential.

The energy crisis put a damper on projections of future electricity demand, so the “grow and build” strategy of utilities seemed unnecessary in the economy that lay ahead. They’d enjoyed a decades-long reign over the enormously-complex electricity system and now, in the eyes of neoliberal reformers motivated by the energy crisis, they needed to face some competition.

Meet the New Electricity Capitalists

Competition in the power sector—against utilities, that is—started with landmark legislation passed by President Jimmy Carter in 1978, the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act. Utilities were forced to integrate and purchase power, at sometimes inflated prices, from the generators of new, other capitalists rather than shooing those capitalists out of their monopoly territories. Those latter capitalists are today known as independent power producers, or IPPs.

Tasked only with marginal power generation instead of public service, this new wing of the bourgeoisie succeeded in developing the productive forces of electricity. Smaller and nimbler gas combustion turbines borrowed technological improvements from jet engines, eventually reaching even higher total energy efficiency—but at a smaller scale—than what the utilities had built. Wind turbine technology began to take off as well, especially in the fertile regulatory soil of California, albeit as relatively unproductive precursors to what dot the landscape today. Solar power, however, wouldn’t get its time in the sun until decades later.

Since those first IPPs were born, waves of restructuring at the federal and state levels have only deepened competition in the industry. Today, it extends beyond the realm of power generation to also include long-distance transmission and, in a dozen or so states, into the realm of retail electricity service.

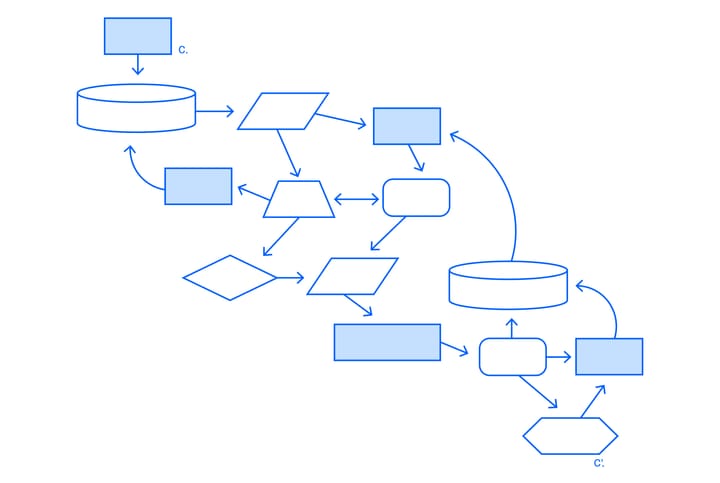

The result is an even more complicated hodgepodge of institutional arrangements—of markets, operators, regulatory jurisdictions, and resource valuation metrics. In New York, for example, eight regulated utilities own, operate, and maintain local distribution lines (except for towns with municipal utilities), while 126 different firms compete to sell retail power to individual customers over those very same lines, for which the utilities bill customers on their behalf. The power they sell is procured over wholesale markets in which 426 firms are buying, selling, or simply trading, all outside the purview of New York’s utilities commission. These markets are instead regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

While the old utility model required socialized planning of investments in line with projected demand, the new system is an uncoordinated morass of short-term profit seeking. New generation projects enter neutral “interconnection queues” to be studied for technical feasibility, an intensely laborious process needed to ensure a reliable grid. Competing IPPs clog these queues with projects, resulting in a nationwide backlog during a time of need; each is looking for the cheapest and easiest spots to connect into the grid, leading to speculative proposals and even more overhead. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that from 2000 to 2017, about four out of five such projects were never built.

In this new electric power sector, at least one development is clear. With the new capitalists duking it out against the old ones, smaller-scale power generation technologies like renewables have grown more mature and more socially useful. Wind and solar now comprise 14% of all electricity generation, up from zero during the Carter administration, and a solid 83% of it comes from IPPs, not utilities. Another new kind of capitalist now has a seat at the table too: energy traders. With the wholesale price volatility created by all that wind and solar—when present, prices fall, and when absent, prices jump—they can make a killing simply from a drop in sunlight due to a morning fog.

The Price of Utility Competition

Competition seems to have been so good for renewables that one might forget it’s also been a process of deregulation: breaking up an industry, scattering both its firms and its organized workforces into smaller pieces, and replacing consumer price regulation with new markets.

Deregulation usually meets some hesitation among liberals and the Left. But in the case of the electric power sector, the lofty promise of environmental improvements seems to override such hesitation. Not so for the labor movement, however.

Jim Harrison, Director of Renewable Energy for the Utility Workers Union of America, evaluates deregulation in simple terms: “We don't think it has lowered rates for people, and secondly, it’s had adverse impacts on employment.” The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, too, has opposed deregulation for decades, such as a recent failed attempt at it in Nevada.

“Good union jobs came out of centralized power plants,” said Harrison. But in the process of deregulation, over a dozen states forced utilities to sell off their power plants to IPPs. This divestiture, he explains, devastated the unionized workforces built up over the decades; union ranks in the sector declined from 209,000 in 1995 to 175,000 in 2002. Sometimes, union contracts at divested plants were lost entirely. Other times, “we’d already had a labor agreement with a utility for 40-plus years, and now we’re negotiating from scratch” with the assorted IPPs who took over. Wages and benefits declined rapidly. “This is our NAFTA,” a utilities union official told Labor Notes in 1999.

As for all the renewable energy spurred by competition, Harrison, unlike virtually all progressive climate advocates, doesn’t necessarily see good jobs. Since the vast majority of wind and solar facilities are owned by IPPs and not utilities, he points out, “that's all non-union! They may have been built with union construction labor, but in our experience, it's hard to find any with union labor in operations and maintenance.” (Those states negotiating large offshore wind projects typically include project labor agreements, however.) Too many climate advocates, he says, talk in terms of abstract work hours estimated by economic models instead of actual union jobs and careers.

Historically, utilities have appeared uninterested in developing their own renewable projects. Asked why that is, Harrison pointed at the landscape of state and federal incentives. One key example that often goes overlooked by utilities’ critics is the tax credit scheme that has subsidized alternative energy technologies like renewables from the very beginning—but only for IPPs, not for utilities, since national energy policy sought to break up the latter. The “tax subsidy bias in [the] IPP dominance” of renewables, geographer Sarah Knuth writes, “have made regulated investor-owned utilities in the United States unable to profitably use [tax credit incentives].” After decades, the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022 will largely dismantle the bias.

Beyond the impact on the workforce, the union’s concern with electricity rates is backed up by evidence. According to federal data, from 2001 to 2021, average real prices for residential customers increased, while those for industrial customers decreased. Research from MIT and Harvard published in 2022 demonstrated that IPPs gobbled up the profits gained through more efficient operations; for residential customers in particular, the deregulated market did not lower prices.

In the traditional utility model, regulators ensure fair prices for the public by checking utilities’ accounting, and approving or curbing investments. When the utility owns and operates the vast majority of the power generation it sells to retail customers, the regulator’s job in controlling retail prices is easier—control the capital investments related to generation. But as Harrison points out, deregulation “decouples retail price regulation from wholesale prices.” Wholesale price signals on the open power markets, where states have little to no policy influence, come to dominate.

The decoupling of wholesale prices from state utility regulation is partly what’s plaguing offshore wind development for those deregulated Atlantic blue states. Wholesale power prices are looking too low, and supply chain costs too high, for those IPPs to see sufficient returns on investment. And that’s despite state climate policies mandating offshore wind procurement. New Jersey even offered an additional $200 million in tax credits to coax its IPP developer into continuing the project anyway, to no avail. In Virginia, on the other hand, the utility commission can adjudicate cost increases in tandem with their effect on retail service.

Harrison cites nuclear plant closures as another downside of the industry’s transformation. When IPPs took over nuclear plants to sell their power on the market—when the plants left the “umbrella” of utility regulation—their sensitivity to wholesale prices became their downfall. Nuclear plants in several states closed down in the presence of lower than expected wholesale power prices despite offering their states low production costs, 24/7 clean energy, extensive tax revenue, and hundreds of high-wage jobs.

The Growth We Need

Offshore wind is a new clean energy juggernaut with great potential, but the heavyweight champion is still nuclear power. Nuclear plants churn out about 20% of America’s electricity and roughly half of its carbon-free electricity. Like offshore wind, they have historically involved construction megaprojects with staggering project costs. The costs of both must come down through repetition and iteration, like the big power plants of the last century.

Last summer, the first totally new American nuclear plant of the century came online: Vogtle Unit 3 in Georgia. A colocated copy, Unit 4, is slated to start this year. Together, they will produce about twice as much electricity annually as Dominion’s huge offshore wind project—and around the clock, too. Unsurprisingly, this “industrial cathedral” was only possible under the umbrella of an old-fashioned regulated utility, Georgia Power.

Democrats and climate activists see Vogtle as a boondoggle that undermines renewables, but Republican state utility commissioners, with broad support from unions, have championed it. That championing was essential, as Vogtle is infamous for lengthy construction delays and an eleven-figure price tag that more than doubled from initial estimates. But the final cost is still drawing scrutiny: how much should be socialized by consumers, and how much should be eaten by Georgia Power’s shareholders?

In the coming clean energy boom, the importance of dogged, publicly monitored regulatory oversight from state utility commissions cannot be overstated—not just to curb utilities’ fundamental interest in their shareholders, but to drive out the kind of moneyed political influence that the utility model has always attracted. That kind of thing didn’t stop a century ago: in recent years, Ohio utility FirstEnergy and Florida Power & Light have made headlines with old-timey corruption and scandal.

But therein lies a path to “clean growth” via the utility model without the capitalists.

Rather than unleashing new capitalists against the old ones, progressives of the New Deal built up competition from the public sector. President Franklin D. Roosevelt channeled popular anger against the utility capitalists—and their captured state regulators—into a political program focused, in part, on publicly owned and operated alternatives. The flagship New Deal public power institution, the Tennessee Valley Authority, today still relies on monopoly to finance and build long-term clean energy infrastructure, though critics want to introduce competition to its service area.

It's hard to imagine the political appetite for such grand institution building today, when the focus remains squarely on competitive procurement of decentralized renewables projects. Unlike when Roosevelt campaigned on public ownership of hydroelectric potential on the nation's rivers, today, there's no political embrace of public ownership of offshore wind projects that similarly depend on leasing public waters.

The limited prospect for big public power doesn't mean hope is lost for clean energy growth today. Though socialists think flatly about the profit motive as the problem tout court, there are disparate models of profit-making that shape institutional capacities for building the long-term infrastructure and organized workforces we need. But where the utility model exists today, many seek to drive it out. In Virginia, where utility-led offshore wind is outlasting projects in deregulated states, the Republican governor recently tried, but failed, to require subsequent projects to go through competitive bids, while Democrats, in partnership with the Sierra Club, are trying to compel the utilities to outsource more clean power to IPPs.

The world of climate politics has embraced them wholeheartedly, but the byzantine markets, auctions, and tradable renewables certificates of competition aren't the only path forward. As it becomes increasingly clear that these market-based models will not "grow and build" at the scale we need, it's time to reclaim the utility of utilities.

■

Matt Huber is a professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at Syracuse University. He is the author of Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet.

Fred Stafford is a STEM professional and independent researcher on the power system, decarbonization, and public power. His newsletter can be found at PublicPowerReview.org.