Remain in Light

In paranoia, as opposed to in psychoanalysis, things always have a deeper meaning.

Flectere si nequeo superos, Acheronta movebo.

[If Heaven I cannot bend, then Hell I will arouse.]Virgil

So walk my friends, in the light of day

Don’t go sneakin’ ‘round no holes

There just might be something down there

Wants to gobble up your soulTownes Van Zandt

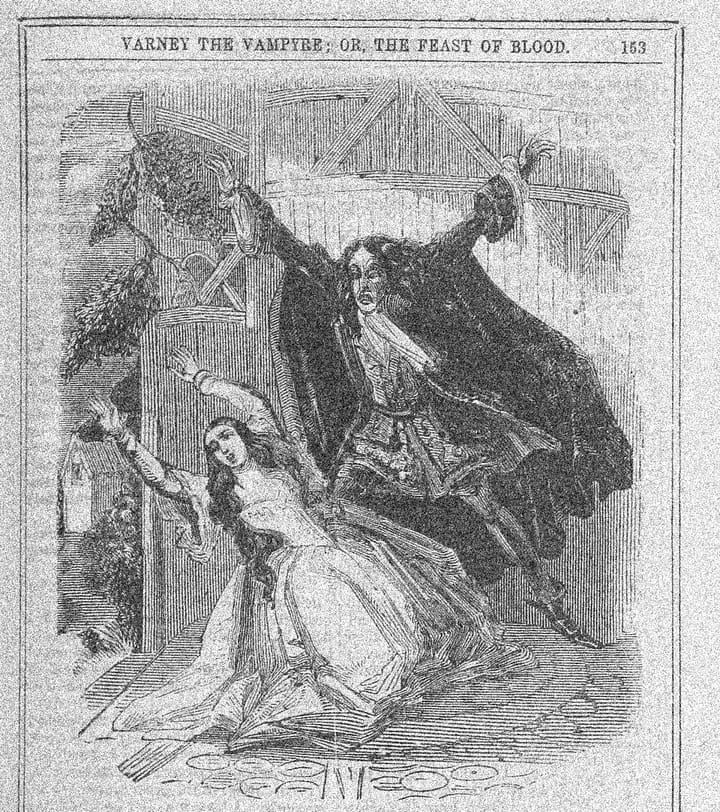

Freud taught us to descend from the light into the darkness of the unconscious in order to understand what was normally hidden from, and thereby structured, visibility. This is because Freud understood that thoughts or impulses that were forced into the unconscious did not thereby become inactive. By being made unconscious, objectionable thoughts simply became active in different and oftentimes more nefarious ways. Finding no place in an impliable reality, they take refuge in the underworld but nonetheless rear their heads in the form of unintelligible symptoms.

The point of interpretation is to trace those seemingly meaningless phenomena (parapraxes, hysterias, dreams, obsessions) back to the repressed thought governing them, and thereby free ourselves both of unwanted symptoms and, more importantly, of servitude to the unconscious.

There is an important if neglected feature of psychoanalytic interpretation that distinguishes it from another more sinister form. Before diving into the unconscious, the psychoanalyst has first to take consciousness seriously. Interpretation comes only at the very end of a long process, and its sole function is to provide meaning where before there was only a chaos of half-thoughts, memories, images, and random details.

In the caricatured version of psychoanalysis, every problem a patient brings in is met with the same answer: “You want to sleep with your mother and kill your father.” It’s true that psychoanalysis gave rise to perverted forms of itself, wherein an overly easy and ultimately dismissive mode of interpretation lacking “falsifiability” was propagated. But we must remember that it was Freud himself who first named and discredited this mode of interpretation, which might be considered psychoanalysis’s nefarious double. He called it paranoia.

Paranoia is defined not by persecutory anxiety but rather by a indiscriminately applied depth hermeneutic. In paranoia, as opposed to in psychoanalysis, things always have a deeper meaning. For the paranoid, there is never first a moment of taking consciousness seriously, and there is no limit to interpretations of meaningless, unwanted symptoms. Interpretations can be applied to all things, including those that are perfectly comprehensible on their surface. And they can be applied at all times, that is, before anything is understood about what is derided as the “surface level.”

The psychoanalyst ventures into hell in order to return to the light. The paranoid lives in – and drags everyone else into – hell; which is to say, the paranoid is always already interpreting, endlessly tearing away veils in order to discover the truth, which is always somewhere other than where it announces itself. What the paranoid lacks, in other words, is the ability to communicate: to take the words of another person at face value and respond to them in their direct intention. The paranoid suffers from a compulsion to interpret, and by constantly drawing attention to the “underlying meaning of things,” their grasp of reality attenuates.

This is not to say the paranoid is not social. Contrary to popular belief, paranoids are not abnormal hermits hiding away in fear from a persecutory reality. Paranoids are in fact obsessed with being well-liked: since they know that external reality is always different from internal truth, they front an intensely pleasant and affable veneer, unburdened by any need to express themselves openly and honestly. For what would be the point in doing so? Everyone knows, of course, that one only expresses oneself with “openness” and “honesty” when something else is going on.

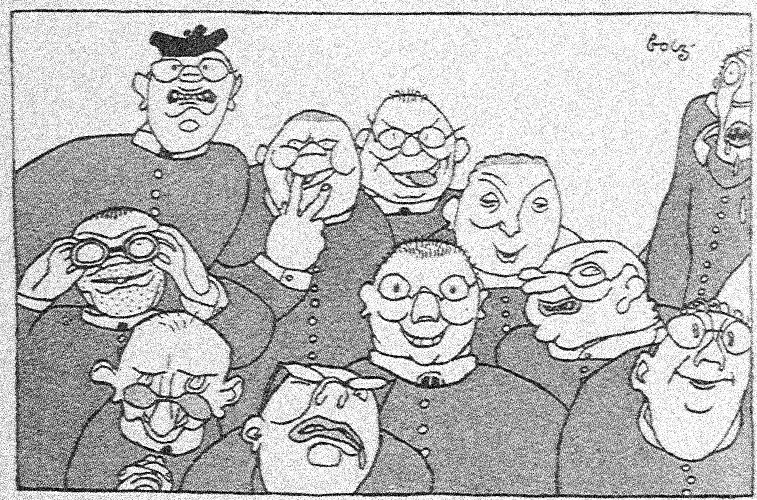

The extra benefit of being well-liked, for the paranoid, is acceptance into what we can call the “inside dope” community. This is the true goal of every paranoid, and the only kind of community in which a paranoid can truly participate. The inside dope community is one built on the idea that truth is always hidden beneath the surface. Whatever is said in public by members of the inside dope community is never the whole story, which must lay hidden and only be shared with other true paranoids.

The inside dope community feels justified in maintaining its inside dope because it assumes that every community is built similarly. If paranoids find themselves in disagreement with another group of people, they assume that the disagreeing group is also structured around some hidden and undivulged principle. No group, thinks the paranoid, coheres without a secret, and it is the secret that separates us, not what’s on the surface.

Whereas psychoanalytic interpretation intends, by freeing subjects of determination by the unconscious, to rehabilitate people for the kind of open, rational, reality-oriented dialogue required for democratic decision-making, paranoid interpretation forecloses the possibility of the same by determining the truth and the content of any particular claim to be always already separate.

It would thus be difficult to overstate the destructive effects of paranoia on political spaces. On first sight of disagreement, paranoids will begin to sense that their inside dope is not the only dope to be had and begin marginalizing anyone who smells of a foreign secret.

Spotting paranoids is, of course, not politics, but it is a skill required to not get trapped by the obstacles to politics. So when someone takes you aside and offers to tell you what’s “really going on,” resist the attractive fragrance of insider knowledge and proclaim, with the well-deserved pride of someone committed to democratic transparency, “No thanks. I’ll remain in the light.”

■

Benjamin Fong teaches, writes, organizes, and lives in the great state of Arizona.