What is a podcast?

The pornography of conversation and the erasure of experience.

The term “podcast” was “accidentally invented” in 2004 by tech journalist Ben Hammersley. The “pod” part was taken from “iPod,” and iPod in turn took its name from 2001: A Space Odyssey. As in, “open the pod bay doors, HAL.”

Podcast is also of course a play on the term “broadcast,” which was coined by Charles Herrold in 1909. Broadcast was a farming term (Herrold was the son of a farmer), which indicated “the tossing of seed in all directions.”

Herrold, who set up the first “broadcasting station” in America (“San Jose Calling,” now KCBS San Francisco), opposed the term “broadcast” to “narrowcast,” a transmission aimed for a specific audience. Tempting as the connection is, podcasts are not narrowcasts, in Herrold’s sense. Narrowcasts have known targets, like a single receiver aboard a ship. The podcast might occupy specific niches, but it is effectively a broadcast, albeit one in an age when so many seeds are being spread that no one expects many to take root.

Of course, the experience of the podcast is quite different from that of the broadcast. The podcast is typically much more casual, often to the point of lacking any clearly definable structure whatsoever. The hope is to create an experience something like stumbling upon an interesting conversation that friends of friends are having at a party.

In this sense the podcast much more effectively carries out the function attributed by the Frankfurt School to the broadcast: to penetrate our interpersonal lives and make our actual relationships more shallow and hardened than they would otherwise be. Personalities on a broadcast are put together, made up, distant. If a rapport is built with broadcast personalities, it is one that is clearly distinct from the one built with friends and family.

Podcast personalities are different: they’re just people talking on mic, and you can imagine being in the room. They often personally respond to emails, and they might even be actual friends of friends. You can’t really imagine the news taking the place of conversations with your friends, but you could in the case of podcasts, especially now, in the time of coronavirus, that the best way to talk with your friends is using the same software on which all podcasts are being recorded.

The parasocial interaction thus never so closely approximates its model—the social interaction—as in the form of the podcast. Podcast personalities might then be understood as substitute satisfactions, though they are often better than the real thing. Everyone likes their knowledgeable and talkative friend who takes up too much conversational space, but in small doses. We’re of course happy for their presence in awkward social situations, but there’s only so much nodding one can do.

Unlike that type of friend, podcast personalities are there when you want them, and gone at the touch of a button. They might not save you at a quiet gathering, but they’ll supply you with enough throwaway takes to take up some conversational space yourself.

They also provide the additional function of better decorating the spaces where we are, in the words of Sherry Turkle, “alone together.” Since the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, podcast download numbers have actually dropped. This is because podcasts are consumed out in the world, on the train and in our cars. They function, much like the EVA pods in 2001: A Space Odyssey, as individual bubbles that help us move through outer space.

In one sense, this is nothing new: iPods and the like provide social protective gear, repelling unwanted conversation and elevating mundane commutes with one’s favorite music. But the pod bears different features when it’s filled with conversation rather than music. Music offers a personal soundtrack, so that you can be the hero of your own life; conversation requires at least some minimum level of attentiveness.

Perhaps the phrase “background conversation” has more purchase than I would like to believe, but I don’t think this quite captures the experience of the podcast, which is more one of foregrounding. In this sense, it is like cinema. As Bernard Stiegler argues, the experience of cinema is one of giving oneself over to the time of the other: “During the 90 or 52 minutes of this pastime, the time of our consciousness will have entirely passed over into the time of these moving images, linked to one another by noise, sounds, words and voices. 90 or 52 minutes of our life will have passed outside of our real life.”

iPod music “enhances” one’s experience; the podcast, like the film, replaces it. But unlike the film, the podcast does not require perceptual focus because, being an actor in Marshall McLuhan’s “acoustic world,” it contains no frame, no limits. The podcast is not bounded; it has no special space like a theater, and again podcasts will mimic this lack of constraint in the structure of their programming, forgoing traditional introductions or narrative arcs.

We can now come to a preliminary definition of the podcast.

What it is:

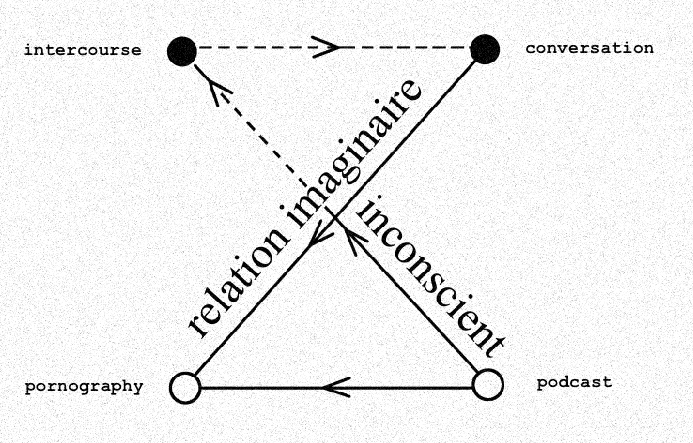

The closest parasocial approximation of conversation available, it is to conversation what pornography is to intercourse.

What it does:

It replaces (predominantly public) experience, a task for which it is particularly well-suited due to its ability to erase time without the boundedness of visual media.

■

Anselm McGovern is Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor of Practice in the Department of Culture & Cuisine at Walden University Online. He is the author of We Could All Probably Be Better at Oral Sex Than We Are Now: Haiku for Life (Forthcoming).