Byung-Chul Han’s Salvage Boutique Shop

Postmodernism disassembled and sold for parts.

Review

The Agony of Eros. MIT Press, 2017.

The Burn-Out Society. Stanford University Press, 2015.

Topology of Violence. MIT Press, 2017.

Saving Beauty. Polity Press, 2018.

Byung-Chul Han writes a lot of books (though they are closer to pamphlets), and they all revolve around three claims. First, negativity doesn’t exist anymore; it’s been replaced by positivity. Second, social violence has migrated from the outside to the inside, from suppression and restraint to motivation and psychology. And third, the punctuation of human life by the erotic and aesthetic experience of the Other—in the jargon, “radical alterity”—has been replaced by an endless stream of narcissistic sameness. These forces combine to create a new kind of subject: “Twenty-first century society is no longer a disciplinary society, but rather an achievement society. Its inhabitants are no longer obedience-subjects. The positivity of Can is much more efficient than the negativity of Should.”

These descriptive generalizations say something true about the experience of contemporary society, but this is all we get from Han: not a why, but a simple that. To obscure a dead-end, his typically acceptable if banal insights are repeated through a glittering, dizzying array of examples. A single essay marshals references to ancient Greek religion, Sigmund Freud’s biological speculations, Botticelli’s frescoes, and Von Trier’s Melancholia. The names of Schmitt, Brueghel, Wagner, Levinas, Buber, Benjamin, Agamben, and Aristotle come and go in quick succession.

After plodding the straight path through this erratic landscape, it’s not even clear that these three points are not ultimately the same. Inference and argument are submerged in a rocking rhythm of conceptual riffs. “Positivity,” “sameness,” and “the interiorization of violence” are autonomous forces in themselves, descriptive generalizations creating cultural phenomena as surely as if they were sketching their own illustrations. Han investigates objective moods: a vague coloring of experiences read off as direct features of the world. The pleasure of the mind tearing at its bonds replaced by that of ricocheting off its own walls.

Cultural criticism always suffers from grandiosity. But, like an infant within a good-enough holding environment, our thinking needs the wild gestures of protected omnipotence in order to develop the confidence to grapple with a reality that is often not immediately legible. There have been grandiose projects to project the power of cultural criticism: to re-found systems of values, to establish faith, practices, and institutions all but commensurate with religions. There have been projects that criticize their own powerlessness in a bid for relief: like a nineteenth-century French novel, pointing out our own self-deceptions and the endless falsehoods by which we muster the courage to go on.

With Han, there’s no attempt to explain causes, to name power, or even to establish a relationship to it. Instead, there is a blank thatness that generates a total criticism without details, cause at once for both hysteria and apathy. Hysteria, because everything becomes an ominous sign of the tightening net of positivity, sameness, and violence; apathy, because the signs are their own causes, powered by their simple existence, closing in, and therefore inexorable.

One surmises that the underlying assumption here is that since, according to the theory, power is interiorized and governs by shaping psychological and subjective reflexes and patterns, cultural criticism is directly political criticism because it is ultimately these patterns, and the cultural formations that both display and reinforce them, that are the site of power in society today. In losing the priority of the object, the telos of cultural criticism becomes its own endless supply chain. Han magically completes the dissociative circle, leaving us to float in a politics without history, philosophy without distinctions, psychology without individuals, a mode of aesthetic critique without any corresponding notion of aesthetic experience. The register of criticism is too narrowly conceptual and desultory to be philosophical or social criticism, yet too general and all-encompassing to be a refracted account of social forces behind any particular experience.

What explains the appeal of this fantasy world? Half-education is marshalled to treat the ephemera of social life—a film, a book, a notion from a philosopher, a study by a psychologist—as if they were signs of an exciting intellectual world where dominating frameworks and regimes of Positivity and Negativity, Interiority and Exteriority, Alterity and Identity, do battle over the fate of the world. The key tropes are like film characters, gratifying readers much as heroes function as identification vehicles to soften the blow of subjectless daily life. True Otherness, the Outside, the touchstone for Han’s critique of a society governed by unthinking sameness and positivity, is written into a placeholder. The plea for the particular taken up in the rhetoric of a criticism devoted exclusively to frameworks loses its last trace of particularity.

Is all of this particular to Han? No. There are dozens of intellectuals who have sold a similar project: the notorious theorists of postmodernism. But something is different here.

As Catherine Liu has pointed out, postmodernism was tied to a political project. Liberation from the frameworks of grand, scientistic narratives of progress was part of a project of coming to terms with the defeat of social democracy and the modernist intellectual currents that attended it. For the postmodernists, regimes of reason and perception were the true causes of domination. The critique of such regimes and the narratives that anchored them was in one stroke political, philosophical, and social. Theory was developed as the genre of this critique, devoted to characterizing speculative frameworks and suggesting alternatives. In this way, the professional-managerial class claimed the mantle of the subject of emancipation by substituting the ethics of intellectual liberation for the politics of social democracy.

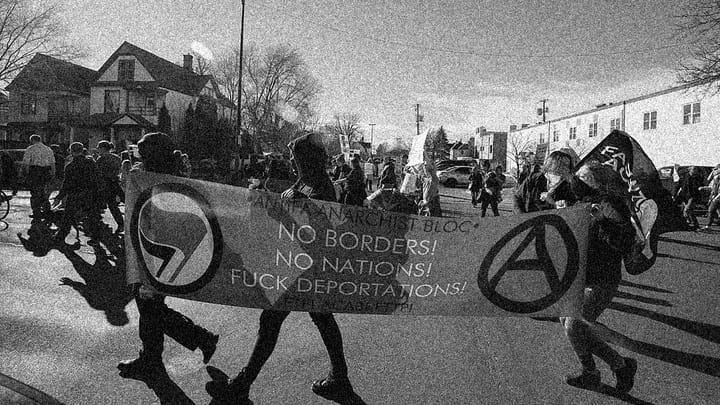

In Han’s work, even the abstract ethos of postmodernism is missing. The equipment of the postmodern arsenal is there, but seemingly for its own sake. His writing is a salvage boutique shop: having been to the junkyards of “theory,” and scavenged for and cleaned up a few of the spare parts, he now has them attractively on display as decorative items. Every one of his sentences could be a Twitter post, and a short one at that: immediately digestible, eager to be recounted by someone partially drunk.

“Theory,” along with its cults of personality, was an academic disease from its inception. It’s done irreparable damage to the humanities and social sciences. But Han is not guilty of its crimes. He is an entrepreneur, and like all entrepreneurs, a peddler of the retro as chic. His books should be understood as retail catalogs: “they extend through the inferno of the same, which obeys only economic laws.”

■

Antoine Doinel is a shoe stock boy in love.