Inside the Mind of the Professional-Managerial Class, Part Two

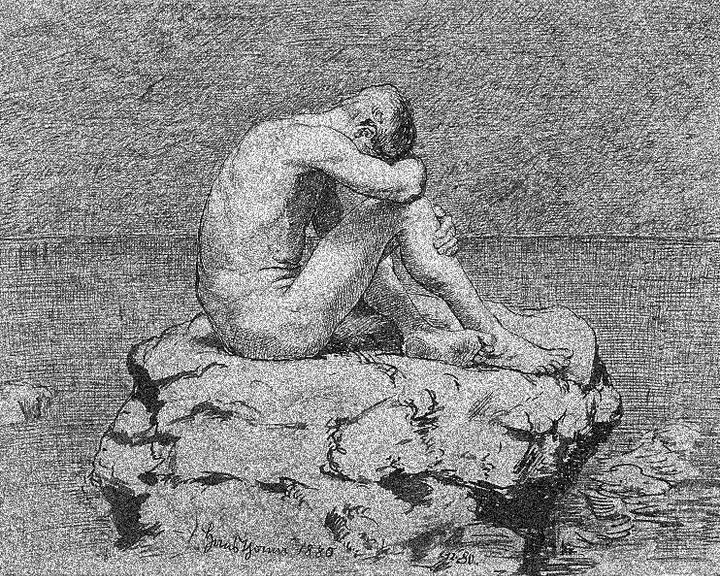

Fear of a breakdown that has already happened.

In this series, which begins here, our resident Bay-Area psychotherapist takes us to the depths of the professional-managerial class psyche. Consider her the Virgil to your Dante.

The following clinical material is fictional, based on composite experience.

In his seminal Fear of Breakdown, Winnicott postulates fear of impending trauma as a defense against trauma that has already occurred. For example, a patient who grew up in abject poverty worries obsessively about ecological disaster. Or a patient whose parent died young of alcoholism experiences nightmares about their child becoming terminally ill. In some basic sense, it is easier to worry about something bad happening in the future (that has not actually happened yet) than to acknowledge, experience, and mourn something bad that happened already. Facing a breakdown directly is overwhelming. It is potentially re-traumatizing; potentially paralyzing. Displacing breakdown into the future allows us to go on functioning, one step removed from reality’s traumatic core. The more terrible the trauma, the more true this holds.

The millennial tech-workers in my San Francisco practice see a bleak future for themselves. Despite faring better than most in their generation, they understand that their life outcomes will be worse than their parents’. Ecological collapse, the erosion of the middle class and welfare state, rampant inequality, profound mistrust of government, defunct politics, intensifying automation—and little grounds for optimism about course correction.

After graduating from college, these patients landed jobs at hyped-up companies in the Bay Area, traveled frequently, partied heavily, got married—intellectually acknowledging our crash course towards planetary disaster and an untenable economy, posting catastrophic articles on social media, and all the while carrying on with business as usual. A definitive, if cordoned off, recognition of doom.

Take Rachael, for example, whose “great job” produced anxiety, panic attacks, and self-medication. “I have no life outside of work, and I hate work so much,” she told me. She pays $3000/month in rent, has massive student loans to repay, can’t afford a car and acknowledges that she’ll have to figure something different out once she wants a house and kids. I observe that Rachael, 33, wants these things now, but she deflects: “That’s future Rachael’s problem.” Rachael focuses intensely on the present because looking elsewhere is terrifying. She can almost convince herself that things are okay now.

Tyler grew up in an upper-middle class family with artist parents. They had a large studio adjacent to their house, and Tyler always wanted to follow in their footsteps. He began college as a fine arts major, but switched to engineering under pressure from his parents—he “would never make it financially as an artist these days.” When he first came to the Bay, he could balance his job in tech with outside artistic projects; once he married, purchased a small condo, and became promoted to “manager”, slivers of time outside of work were spent merely recovering. He and his wife talk about moving out of the city one day, perhaps up to Sonoma County, but the cost of living is high there, too—and besides, what would they do? “Can you imagine us in the country?” he grinned, “We’re unequipped to make it elsewhere.”

The COVID catastrophe has put our failed state, disastrous healthcare system and precarious economy on gruesome, ostentatious display. Some hope this revelation will impel change, and that neoliberalism’s death blow has finally been delivered. The truth, however, is that the current COVID crisis does not tell us anything we don’t already know. Rather, COVID punctures the defenses we’ve built against confronting this reality—against emotionally experiencing its traumatic impacts. It plunges us into what Winnicott describes as the “unthinkable state of affairs that underlies the defense organization.” It puts us in terrifying visceral contact with the damage already done—the damage my patients have spent their whole lives projecting into the future.

The economic fallout from the current pandemic has upended many of their lives. Rachael lost her job overnight. Fahad, who devoted himself slavishly to his independent tech marketing enterprise, filed for bankruptcy. Mia, a single mother of two, has been furloughed with a deadline that keeps getting extended. Tyler isn’t worried about his own job, but has had to lay off most of his team and feels devastated.

These people are living the reality they have always known and feared—and yet, seem strangely astonished. Shocked exclamations proliferate: “It’s like we’ve been transported to a whole different universe! Who in January could have possibly predicted this?!”

I push back, remembering our many conversations about economic and ecologic precarity, social unrest, and political leadership: “Well, I mean, not precisely this, but in a general sense, um, you and I.”

The surprise holds: “I never imagined things could be so bad in this country. Here! It’s the kind of situation you think would only happen somewhere else. I feel completely disoriented.”

My patients knew about this breakdown, and yet they didn’t know. The defense in some important sense prevented actually thinking about it. In psychoanalytic terms, it stunted ego development. Because traumatic material circumstances were never confronted, mourned, or creatively and collaboratively worked through, facing this reality now is overwhelming. Rachael, for example, manically applies for jobs roughly equivalent to the one she just lost, despite the desperate odds. Fahad moved home with his parents, and cannot think about his next steps. He cannot imagine the future. Mia’s panic intensifies as the months drag on, but she focuses obsessively on the increasingly unlikely possibility of resuming work as usual.

No doubt most people would feel traumatized and disoriented facing a frightening pandemic or losing a job. But because, in the cases I describe, this breakdown is a trauma long known yet warded off, it is particularly paralyzing. Exhaustion and despair lie just beneath the manic defensive perseverance. It reminds me of patients whose parents stayed together for years, despite mutual hatred or other shades of misery, then finally divorced. For these patients, the divorce is more disorienting than for patients whose parents separated early on, or who separated later after years of happy marriage, followed by novel problems—even though they’ve always known divorce was a strong possibility. They’ve soldiered on despite the trauma that has already happened, but never fully happened. They’ve developed strong defenses over a stunted ego and they neither know how to go on nor how to stop.

Responding well to trauma involves organizations and relationships that allow us to retain the capacity to think and feel, mourn, make difficult choices, and articulate new stories. A relational container or holding environment, to use Winnicott’s words, allows us to navigate traumatic circumstances. A sustained relationship with a sturdy listener enables us to directly confront difficulties, bear associated feelings, and develop alternatives, in lieu of defensive avoidance or psychotic overwhelm.

Absent these conditions, we’re lost to paralysis, vertigo, fantasy—we ourselves fall apart—or, if at all possible, we continue to practice displacement and denial, which generally involves clinging to habituated routines.

In brief moments, as the months wear on, patients give voice to despair. They relay how hard they worked in college, the long, long hours at their current job, wasted years they can never reclaim, a promise purchased but never delivered, a promise that they knew was hollow anyway.

Terrified of COVID, of economic meltdown, of Trump supporters, of reality as they have always known it, my patients work even harder in their doomed endeavors. And no doubt they will continue to cling to a normal that never really was—because the sordid reality in which they have done better than most is as inhospitable as it’s ever been.

Therapy might appear hopeless in this situation, but I’ll end with Winnicott: “All this is very difficult, time-consuming and painful, but it at any rate is not futile. What is futile is the alternative, and it is this that must now be examined.”

■

Lizzie Warren, PsyD, meanwhile, remains in SF, locking herself in to lose herself in Facebook.