I Saw Love Disfigure Me: A Review of Adam Curtis’s "Can’t Get You Out of My Head"

To see how everything fits together, first you have to break it apart.

Eventually, the world stops making sense for everyone. For Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, it happened in 1992, when a piece of shrapnel broke through his skull, lodged itself in his brain, and instantly scattered twenty years of memories. When he woke up in hospital, he couldn’t even remember his own name: all he had were flashes, instants of someone else’s life. “Moments of intense loneliness as a child, of watching Pluto meet an angel in a Disney cartoon, of fear in combat, the smell of perfume, the anger he felt at friends, moments of sexual desire, and the sensation of autumn coming on.” He had strange dreams: a ghostly woman pinning him to his hospital bed, hungry. He wrote about them in his diary. “I felt shameless kisses; as if another tongue was sucking mine… I felt a chest of a woman, two full breasts sticking to my mouth.” Trapped inside, between the bright chaos of the daytime and the temptations of the night, he slowly pieced together his life.

He learned that he was a Palestinian who had grown up angry and confused in Saudi Arabia. Officially stateless, a foreigner everywhere, raised in the gaps of the world. Maybe this was why he had ended up turning to jihadism. A titanic narrative of good against evil, something that could make the world cohere. The struggle took him to Afghanistan, where fighters from across the Islamic world were still trying to overthrow the Communist government in Kabul, the last outpost of the vanished Soviet empire. He had adopted a nom du guerre: Abu Zubaydah. This was where the shrapnel broke his skull.

Ten years later, in 2002, Abu Zubaydah was arrested in Pakistan and handed over to the CIA, who claimed that the man in their captivity was a senior aide to Osama bin Laden. He was not. In his diaries, he’d described the extent of his jihadi activity after he lost his memory; it mostly consisted of trying to berate his host’s daughter into wearing the niqab. It didn’t matter. Shuttled between black sites from Thailand to Poland before finally being deposited in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Zubaydah became the first person subjected to America’s new refinements of torture—techniques intended to break his mind into fragments, grind it down and sieve out the truth.

But Abu Zubaydah was already in fragments. He gave his torturers the information they wanted: he told them that the Iraqi government had supplied al-Qa’eda with chemical weapons, and that vast plots were underway to attack the American homeland. These plots had never existed; they were cobbled together from flashes of action movies Abu Zubaydah had seen as a child. America’s fantasies of its own destruction, refracted through a splintered psyche, suddenly became something else: the secret conspiracy, the narrative thread running through everything, the thing that made it all make sense.

Abu Zubaydah is just one of the people we meet in Can’t Get You Out of My Head, Adam Curtis’s magnificent swamp of a documentary series (available on BBC iPlayer if you’re in the UK, and bootlegged on YouTube for everyone else). Over the course of six episodes and eight and a half hours, we run through the history of the postwar era in dozens of strange personal narratives. There’s Jiang Qing, who starts out as a cynical, social-climbing B-movie actress in 1930s Shanghai, and ends up orchestrating the deadly conformism of the Cultural Revolution as a kind of enormous mass sacrifice to herself. There’s Michael de Freitas, the small-time gangster who brilliantly diagnoses the British national psychosis, attempts to start a revolution, but settles for leading a murder cult. There are the seemingly disconnected stories of a trans woman’s struggles with the NHS and the collapse of the gold standard, Russian prison gangs and the Illuminati, factories closing in Yorkshire and opening in Chingqing, politicians fucking models, the Tupac hologram, Boolean logic, Skinner boxes, the assassination of JFK, the Opium Wars, the rise of the Islamic state… It’s a mess. Like all of Curtis’s previous work, globbed together in one great lump: the systems theorists from Pandora’s Box and All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, the Salafi reactionaries from The Power of Nightmares and Bitter Lake, and the Soviet dissidents from Hypernormalisation. The same intricate use of archive footage; bits of ephemera, junk-film, stitched together with Burial or deep cuts from Selected Ambient Works Vol. II.

Some of these juxtapositions seem to promise some kind of vast insight, even if its outlines remain hazy. In particular, the way he has the Chinese Cultural Revolution rubbing up against the digital revolution scratches a very specific itch for me. I’ve been convinced for quite a long time that these two things are somehow deeply connected in ways we barely understand. In both cases, we were promised a new kind of total, unguarded freedom; in one gesture, we could tear ourselves away from all the musty old structures that had imprisoned us. Become your most authentic self, become multiple selves if you like. There are still some Maoist groups that laud the Cultural Revolution as the highest pinnacle of human freedom; Alain Badiou has echoed this line. In a way, he’s not wrong. It was something “uncontrolled”—networked, decentered, a cybernetic space of total impunity. The big-character posters: a kind of early social media. Formally, you can announce whatever you want—but your expression always depends on the medium and the moment, both of which reward feverish denunciations and violence. This tends towards an emergent conformism; total freedom becomes indistinguishable from total control. The clincher? One of the epithets that the Cultural Revolutionaries gave to Mao was the title of Great Helmsman. In Greek, kybernetes.

But what is Curtis trying to say with this bricolage? Reviewers, even the ones that praised the series, haven’t been able to agree. According to the Guardian, it’s about how the world is “made up of strata of artifice laid down by those more or less malevolently in charge.” For the Telegraph, it’s about how “individualism has both been a symptom and a catalyst for the crisis of authority in today’s politics.” And per the New Statesman, it’s about how we’ve all ended up “aspiring to nothing except material plenty and disabused of all hope of transforming the world.” For what it’s worth, I think all of these are true, but they all still miss the point. These commentators aren’t outside of Curtis’s history, looking in; they’re just more of his characters.

After the JFK shooting, Curtis tells us, DA Jim Garrison developed a new technique for uncovering the hidden truth of the world. “He called it ‘Time and Propinquity.’ You didn’t bother with meaning or with logic. Instead you look for patterns: strange coincidences and links that may seem to have no meaning, but which are actually tell-tale signs on the surface of the hidden system of power underneath.” This is the method of conspiracy theory (and, incidentally, psychoanalysis), but as the films point out, it’s also the mechanism behind Big Data, our entire system of rule by algorithm: trawl through the information we slop out into the internet, and find the coincidences, the connections. The internet doesn’t just provide a platform for conspiracy theory; it’s made of conspiracy theory. People who liked that also like this.

Curtis is a fierce critic of this method. But at the same time, he dramatizes it; this approach is also his own. It’s what has us flashing from the dynamics of coal and oil to sexual politics in the Home Counties to weather systems simulated on electric circuits, all in five minutes.

Can’t Get You Out of My Head is about the voids of meaning that have opened up across the world. In Russia and China and America, with the collapse of the old revolutionary ideals; in Britain with the loss of empire; in Saudi Arabia with the empty suburbs that rolled out over the desert. It’s about our attempts to find some kind of pattern, some meaning or purpose, in the chaos of this reality. It’s the history of the modern world as told by Abu Zubaydah.

And in a strange way, it works.

There’s a line you often hear from cultural-critic types: that the totality of capitalism (or modernity, or whatever) is unrepresentable. Because capital suffuses everything and surrounds us everywhere, and because the tools we use to think about our social reality are also part of that reality, it’s impossible to create an image or even an idea of the thing we’re facing. In one sense, this isn’t quite true. Capitalism is the production of exchange-values: five words, easy. But there’s still something elusive at work.

Capital has a nasty tendency to play both sides of every equation. Do the ruling forces in society want you to bury your feelings? Are they trying to lock them away with psychological repression or prescription drugs, to keep you obediently working and consuming as part of a cold and rationalized order? Yes. Or do they want you to express your feelings, to turn your workplace into a therapeutic community, to make you into a craven narcissist too wrapped up in your own petty interpersonal grievances to form any bonds of solidarity with others? Well, also yes. But how can it be both? Capital is both agglutinative and atomizing, patriarchal and feminized, puritan and hedonist, liberatory and coercive. It wants everything from you. It doesn’t care if you live or die. The whole system is made of its own fatal contradictions.

In an early short story, The Flash, Italo Calvino describes an encounter with that totality. For an instant, his character understands the absurdity of everything, “traffic lights, cars, posters, uniforms, monuments, things completely detached from any sense of the world.” He starts to shout in the middle of the street. “Stop a moment! There is something wrong! Everything is wrong! We are doing the absurdest things. This cannot be the right way. Where can it end?” But as soon as he speaks, the revelation vanishes; all he sees is ordinary social reality, working exactly as intended. For me, at least, this touched something. Why cars? Why traffic signs? Little houses on wheels, trundling around to a system of coloured lights—what were we thinking? Once we were nomads; we stalked under the empty sky and worshipped the creatures we hunted. Once we lived in a living world. How did we end up as the moving parts in this enormous system of extraction and control?

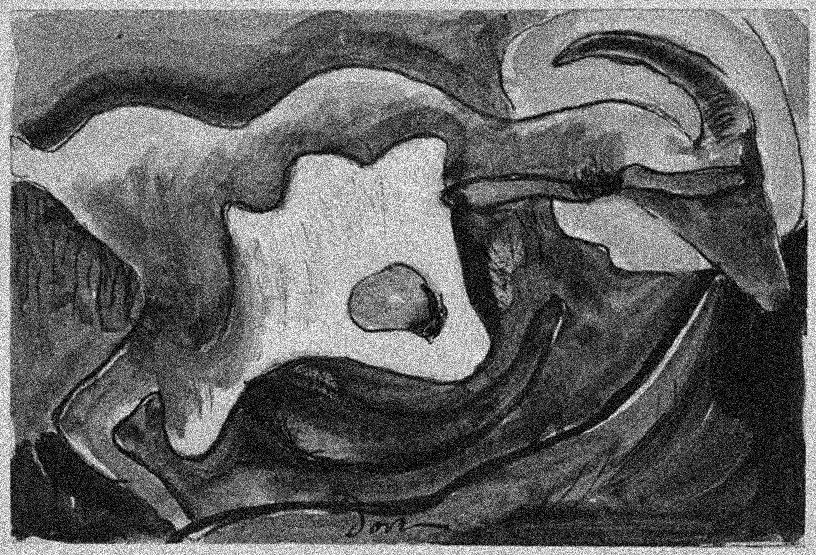

Once, producing this kind of flash was the function of great art; this was the project of the big modernist novels. But as Curtis mentions in an interview on the Red Scare podcast, “there’s very little art trying to capture that strange incoherent feeling of how now feels.” Well, what about himself? Curtis usually insists that he’s a journalist or historian; he tends to bristle at being called an artist. Frankly, he can bristle all he likes. What distinguishes these films is their long abstract sequences of wordless video collage set to music. This stuff isn’t history, and it certainly isn’t journalism. Often there’s a kind of impish irony, like when he has ISIS fighters parading through Mosul to the strains of a priggish English fairy opera. Another shows Google’s Deep Dream AI transform the world into a swirling endless nightmare-landscape of dogs, an iridescent Lovecraft-creature made of wet snouts and floppy ears. Lyrics: I saw love disfigure me/ Into something I am not recognizing…

These moments are moments of art, and they’re not just window-dressing. They’re the most nakedly political part of the series, far more so than Curtis’s narration or his David Graeber references. These silly, playful juxtapositions are where the real intellectual work is taking place. As Eisenstein proclaimed in A Dialectic Approach to Film Form, “montage is an idea that arises from the collision of independent shots,” one which allows “wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects.” This is actually a very strange notion: that an idea can emerge out of a simple concatenation of things. But it works. In Calvino’s story, there’s a kind of textual montage: “Traffic lights, cars, posters, uniforms, monuments.” As soon as they’re named, the flash is already starting to burn.

In one of Curtis’s montages, at the end of the fourth episode, we see colonial-era British soldiers marching in formation to Johnny Boy’s You Are The Generation That Bought More Shoes And You Get What You Deserve. Then it’s dolls on a production line in China, fluttering their sweetly creepy eyelashes, then Fu Manchu, drinking from a beaker of something fizzling and evil. His maniacal grin. The head of a waxwork Putin being delicately, tenderly affixed to his body. Now we’re looking through the eye of a biometric camera; people file past with their faces locked in green numbered boxes. Klansmen raising torches, cops raising guns, a cursor connecting to the internet, a woman smashing a mirror… It vanishes as soon as the music ends, but for a moment every past and present evil comes together: the revelation of a world.

This is the most basic gesture of analysis. To see how everything fits together, first you have to break it apart.

■

Sam Kriss is a writer and dilettante surviving in London.