The Trouble with “Defund”

There is nothing progressive about austerity.

In June 2020, at the height of protests over George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the Minneapolis police, cities across the country took up the call to “Defund the Police.” In Burlington, Vermont, the ultra-liberal city council passed a resolution that aimed to set a new lower cap on the number of police officers in the city, which involved a 30% reduction in the overall size of their force.

Burlington was not alone in cutting police funding. Since the slogan took off in the summer of 2020, several cities have cut money or otherwise shifted resources from policing budgets, including New York, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Baltimore and Oakland. But after a year of “defund” experiments and bitter debate, the results have not been encouraging. In Burlington, to deal with a policing shortage, the city unanimously voted to “effectively write each remaining officer a $10,000 check to stay on the job.”

Of those cities that chose to “defund,” Burlington’s problems are not an exception but the rule. Why the about face? 2020 saw the single greatest yearly increase in homicides ever recorded. As Will Bunch of the Philadelphia Inquirer points out “Some 5,000 more Americans were murdered last year than in 2019—a figure more than the U.S. death toll in the entire Iraq War.”

Despite the policy reversals, the “defund the police” saga isn’t over. Liberal officials are now scrambling to square the circle between activist demands and widespread concerns over public safety. Democratic Party strategists have been at pains to downplay the significance of the slogan and to mitigate any political damage. Meanwhile, many on the activist Left still believe that defunding the police is essential to their progressive project.

The slogan captured a moment of outrage at a clear case of injustice when George Floyd was murdered. It felt like a real protest against “law and order” conservatives and the liberal establishment (even Obama had to chime in to oppose it). Progressives asked: why should cities pay so much for these miniature armies while libraries and schools remain underfunded? And besides, do cops really keep us safe?

But while outrage and intrigue make great social media campaigns, splashy headlines, and email fundraising pitches, they don’t make for good public policy or effective politics.

The truth is, defunding the police is an awful idea.

Slogans and Solutions

From the start, there was confusion over how seriously we should take the defund slogan, which is never a good sign for a successful political demand. Many progressives insisted that “defund the police” didn’t literally mean defunding the police: it meant reallocating police funds to social services. Countless editorials tried to explain what the slogan actually meant—invariably in terms more palatable than those used by protesters.

Slogans ought to simplify. They should capture a broad mood and offer a digestible solution. The anti-slavery movement cried “Free labor, free soil, free men!”; trade unionists in the 1880s proclaimed “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest and eight hours for what you will”; the suffragettes demanded simply “Votes for Women!” These were straight-forward, popular, and sticky slogans. They not only accurately expressed concise demands, but they also expressed those demands in the most attractive terms possible. And I don’t know of any suffragette newspapers that claimed they didn’t really want “votes for women.”

But the problems don’t end with the messaging. Even if you could stomach the phrase, the policy idea behind it provides no solution to the complicated issues of crime and police. “Defunders” used a Robin Hood argument: rob from rich agencies (policing) and give to poor services (education, public housing, health care). To advocates, reallocating funds would help solve the problem of policing by reducing the number of cops, and it would help address the problem of crime by funding social programs. A quick glance at the state of American municipal budgets shows that this formulation was always a journey up a blind alley.

Progressives rightly argue that in America policing replaced any attempt to solve the social and economic causes of crime. As more money poured into big police departments in major cities, less was available for social services and public goods. From this premise, however, activists wrongly assumed that to reverse this trend, you simply have to reverse the flow of cash.

One big reason that cities opted to use policing as the main method of crime deterrence, instead of providing high-quality public services, is simply because policing is cheaper. Funding education, health care, and public housing complexes costs more than funding a police force. A lot more. According to the Vera Institute of Justice, the combined national estimate for the cost of policing totals around $115 billion per year. That may seem like a lot, but as a point of comparison, the cost of all K-12 education is around $640 billion—the Medicare budget alone is $683 billion. Of course, we don’t pay for police and education out of the national budget, but whether Congress, a state legislature or a city council approve the budget is irrelevant. There just isn’t enough money in policing to effectively fund other public goods.

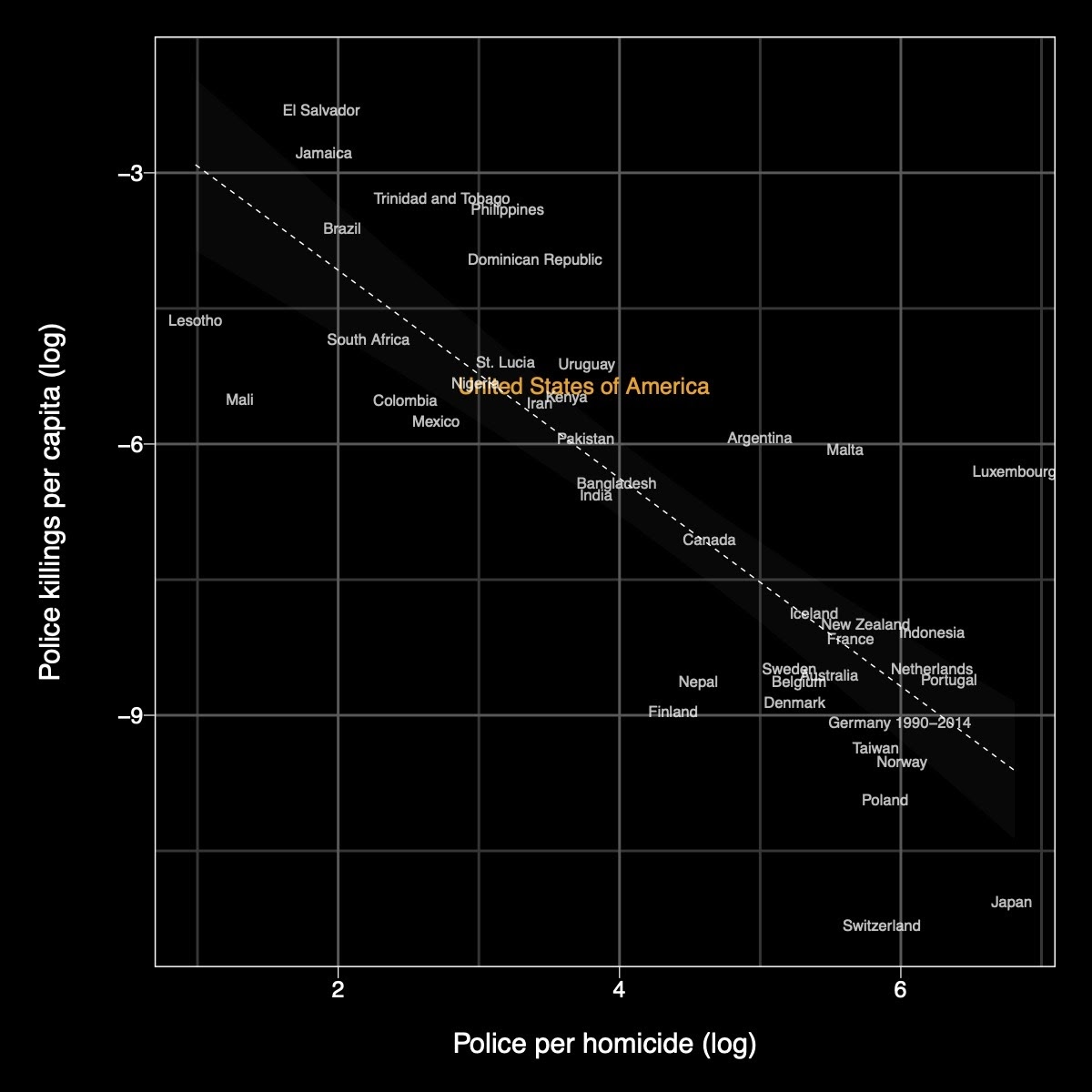

But for some protesters, reallocating funds to address upstream causes of crime is only a secondary goal: reducing the presence of police is the primary objective. In her New York Times editorial, “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police,” Mariame Kaba calls for cutting the number of police officers in half nationwide on the road to “abolition.” The argument is simple: cops kill innocent people, so if we had fewer cops, we would have fewer killer cops. Except the evidence points in the opposite direction.

The United States has fewer police officers per homicide than nearly all other rich countries and at the same time has more incidences of police murder than all of these places as well. The correlation here is striking: more police officers per homicide seems to correlate to fewer police killings. There are surely a number of reasons for that relationship: more police typically means better funded public services. Fewer police means fewer partner patrols, leaving a lone police officer to handle heated situations. Fewer officers also means more police fatigue from longer shifts and irregular hours. But whatever the causal mechanisms involved, there is no available evidence to suggest that we can solve the problem of police violence by shrinking our police force.

Still, others argue that, in fact, the police don’t keep us safe, or even that getting rid of the police would make us safer. Neither of these claims are backed up by the available evidence. Even the ultra-woke NPR had to admit that better funded departments help make cities safer. In fact, according to a recent working paper, not only do well funded departments save lives, but “in the average city, larger police forces result in Black lives saved at about twice the rate of white lives saved” (emphasis added). Despite the often overheated rhetoric about the effectiveness of policing, the data is clear that police do prevent crime, and weaker, more underfunded departments are the worst offenders for violent police activity. Calls to defund, dismantle, and abolish the police seem to defy the available evidence and common sense. Yet questioning such calls remains taboo among educated and progressive people. Why?

The Causes of Carelessness

Despite the evidence, many on the Left continue to advocate an unworkable solution. What’s worse, the heavy focus on “defunding” has made many progressives insensitive to, and even careless in the face of, the ongoing gun violence crisis. Progressive journalists and politicians, NGOs and academic institutes, have downplayed the recent wave of violent crime even as many of their constituents and neighbors raise concerns. In their effort to spin the data, The Guardian ran with a particularly disturbing boldfaced header: “A rise in murders, not a rise in crime.” This is a sadly predictable mistake.

If you look at a map of where progressives and socialists live and lay that map on top of one that plots homicides, you’ll find few spots where homicide hotspots and progressive enclaves overlap. Today’s Left is a highly-educated group, and highly-educated people tend to live in affluent areas where they enjoy relatively comfortable, crime-free lives. You can walk through the center of any coastal city and find leafy middle-class neighborhoods with low-rates of crime and relatively high incomes. But the moment you leave these safe areas the picture is different. According to criminologist Richard Rosenfeld, 50% of the increase in homicides in St. Louis occurred in only six of 79 neighborhoods, representing just 7% of the city population—areas where Cori Bush conspicuously underperformed in her 2020 primary election.

In reality, public safety has become a major concern for working-class voters—the very same voters that progressives are struggling to win over. In Detroit, a recent poll showed that, after education, public safety was a top priority. Black residents listed public safety as their number one concern, while police reform was dead last. For white respondents, police reform was more important than public safety. And to drive the point home further, in Minneapolis, the only group for whom the demand to “defund” was even marginally popular were whites and those with a college degree.

This is a stark social divide.

After decades of Fox News propaganda and over-harsh punitive policing, professional-class progressives think that any mention of crime feeds a politics of racist repression. Yet by taking a position that emphasizes the wrongs of policing and ignores the wrongs of crime, today’s “abolitionists” have helped set up a false choice between ensuring public safety and protecting civil rights.

The problems with defund have not been met with a more realistic attitude but instead with advocates who are willing to go to great lengths to defend their position. Part of the problem is that many on the Left have become “oppositionists”; they are more comfortable advocating for the direct opposite of whatever they think conservatives believe than coming up with genuinely progressive solutions. They wrongly assume that because police officers and departments can sometimes be the cause of injustice, they must always be a barrier to justice. They think that because the persistence of crime is weaponized by the Right, the existence of crime must be denied by the Left. And, like a kid who hurls insults at his parents, they assume that their slogans are both morally righteous and practically inconsequential.

When this kind of political recklessness meets an anxious public in the midst of a crime wave, progressive political aims suffer. On the national stage a large majority of Americans see crime as a major issue and Republicans have been quick to point out the supposed lawlessness of “Democrat cities.” Gun violence is the product of hopelessness and despair bred by poverty, social alienation, and personal degradation. It is tragic. And the tragedy is compounded by the fact that liberals, progressives and socialists won’t address the problem with the seriousness it deserves. Of course, conservatives have no real answer either. Their own unwillingness to confront the massive problems of Gilded Age inequality and cheap and easy access to guns in every corner of American life, combined with ridiculous rhetoric that prizes mob justice, cowboy vigilantism, and individual freedom over collective social responsibility, can only encourage more violence.

Still, their appeals win when the Left is unable to formulate a position that convincingly addresses concerns about public safety.

In League with the Privatizers

The consequences of adopting the “defund the police” slogan stretch beyond simple election risks. After all, there are many times when political principles should trump political expediency. Is this one of them? What socialist principle claims that the best way to fix an institution is to starve it of money? Progressives, it seems, want to punish police departments in much the same way George W. Bush wanted to punish poorly performing public schools. Yet the truth is cutting public funds has never led to more responsible, cleaner institutions; instead it usually results in less efficient, more fraud ridden, and certainly less effective services.

Ironically “defund the police” has had considerable success in large part because it offered cash-poor municipal governments a means to offload some of their financial burden. During initial pandemic restrictions (when advocates for defunding were most active), expected tax revenue for many cities had suddenly vanished. Economic lockdown meant no money was coming in to fund essential services, education, and municipal infrastructure projects. Initial cuts to police budgets were no doubt a response to these budgetary shortfalls—it just so happened that city governments found a convenient ally on the bluffs of a fiscal cliff.

But if municipalities continue to divest from public safety, the demand for private security in affluent neighborhoods will grow. Los Angeles has already begun experimenting with private security to supplement the public police force—newer ventures come with an app-based on-demand service. The only thing worse than a dystopian future where Uber-for-Cops protects gilded neighborhoods while private police drones patrol the poor is the fact that socialists have found themselves unwittingly advocating for that future.

Are we willing to invite the dismantling of public services in favor of private protection rackets, private security, and private profits? Or are we brave enough to fight off left-wing psychological demons and admit that reform is not only possible but preferable? Are we strong enough to accept the idea that public safety is not at odds with civil rights, but at one with them?

Responsibility or Irrelevance?

The violence in our cities is one of the most powerful indictments of contemporary American society, and chiefly our economic structure and its attendant inequality. Solutions to the problem of policing and public safety should be ambitious and far reaching. Defunding, abolishing, or dismantling police, no matter how these demands are framed, is wrongheaded not because it is too radical, but because it cannot meet the challenge of addressing the social causes of violent crime and effective police reform.

The United States is a much more violent country than most other rich nations. To address that we will need both a competent police force and generously funded public services to ensure public safety; right now no city has enough money for either. In some cases money may be badly spent: I’m certain there is fraud and waste in the NYPD budget. In other cases there isn’t enough money to pay officers more than minimum wage. This is true for many areas in and around St. Louis—one of the cities most afflicted with gun violence and most infamous for police violence. But in no case can any city afford Nordic style spending to achieve Nordic levels of public safety.

Fixing policing and addressing the underlying problems of crime will cost billions of dollars. Significantly more money is needed for training and recruiting competent officers, developing independent review boards to investigate misconduct, and yes, putting more officers on the street. More money is needed for reforming the broken courts system. More money is needed for building more humane, sanitary, and safe detention centers. And more money is needed to address the root causes of crime: lack of good jobs, housing, education, and hope.

For a brief period, a populist socialist politics that called for this kind of public investment was on the mainstage all over the world. But starting with the end of the Sanders campaign, and accelerating dramatically throughout the pandemic, we have watched a backward slide in progressive politics typified by a turn away from a popular economic program and toward “woke” radicalism. Consider that before the pandemic the single most prominent demand of the Democratic primacy contest was Medicare for All. Yet weeks after Bernie’s exit from the race, during the largest public health crisis in modern history, all discussion of health care reform was wiped from the table. At the same time, in the middle of the greatest homicide surge in a generation, progressives found themselves swept up in an ideological hurricane advocating a backward and deeply unpopular policy. In a flash, the progressive political world was upended.

It wasn’t long ago that Jeremy Corbyn advocated for more not less spending on police, and Bernie Sanders rejected calls to defund. These positions reflected an acknowledgement that the public craves police reform that results in better policing, but not fewer officers. There are plenty of solutions available—like introducing national standards and centralized federal funding for police departments—that could show a progressive way forward on public safety without surrendering the need for reform.

Unfortunately, many on the Left seem content to float along an ideological lazy river where social media trends dictate policy positions. It will take a brave, serious group to swim against that current. Still, swim they must: if the socialist movement and larger progressive forces continue to insist on crime denialism, defunding the police, and “abolitionism,” it will show that today’s socialism is not only immature, but irresponsible.

Not only insignificant but soon irrelevant.

■

Dominic King is a writer from Cleveland (but temporarily a content creator living in Brooklyn).