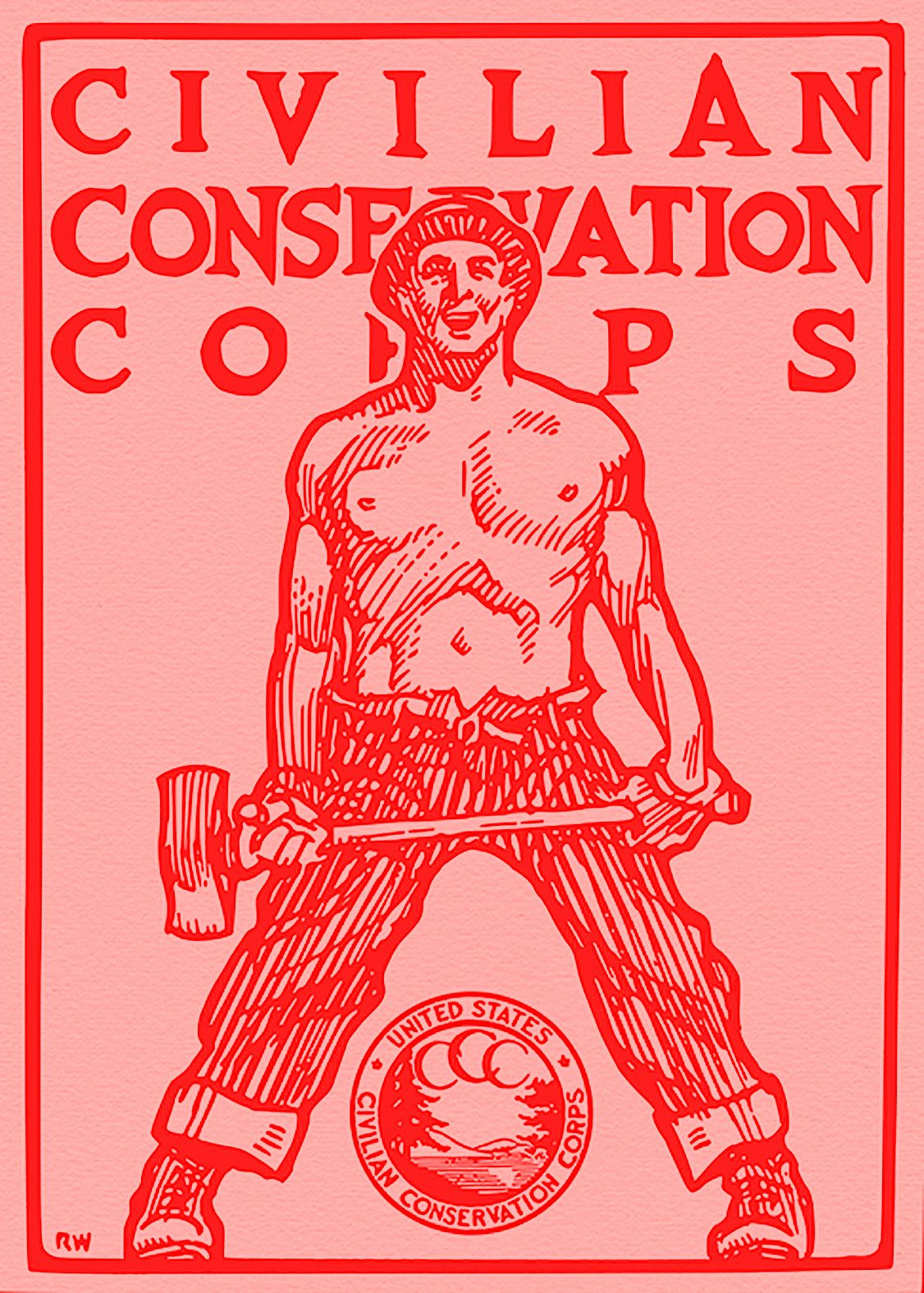

Being a Soil Soldier

The Civilian Conservation Corps did more than prime the economy from the bottom up and restore the land. It also gave many young men meaningful work for the first time in their lives.

The Great Depression hit southernmost Illinois harder and earlier than the 1929 bank crash. All three of the region’s economic industries—agriculture, timber, and mining—were no longer sustainable by 1929. Some mining counties in the region suffered the country’s highest unemployment rates. Families were without food. The once lush million-acre hardwood…