Big Public Power from the River

The Tennessee Valley Authority was about more than electrification. It was a complex project of building state and public planning capacity geared toward rapid ecological restoration of the entire region. For impoverished farmers, it was nothing short of life changing.

Editor's note: Damage Issue 1: Building Big Things features multiple "Then" and "Now" vignettes. This article is one of the former; its companion,"Big Public Power from the Atom," can be found here.

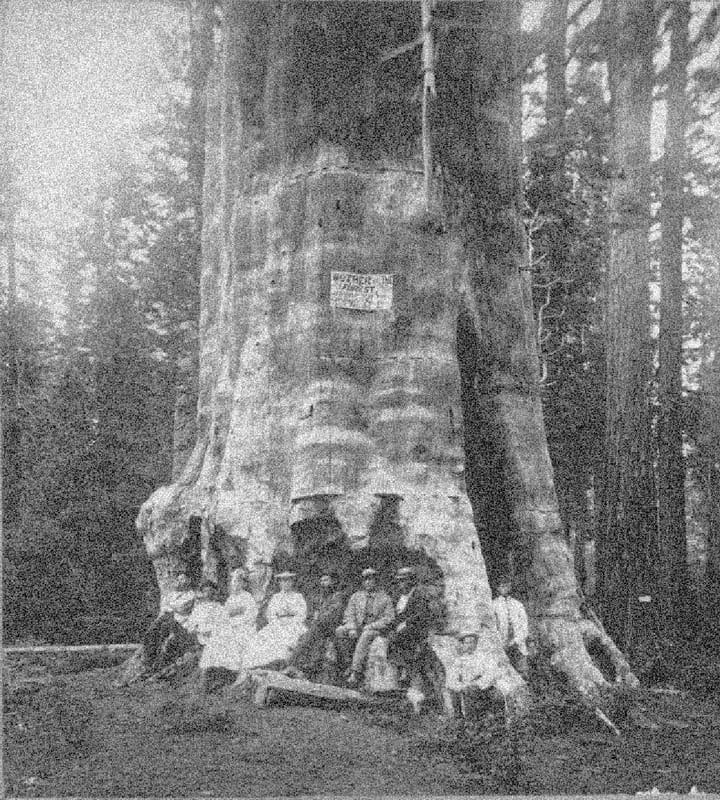

The River giveth, and it taketh away. The Mississippi and all its tributaries brought predictable and devastating floods to communities all across the Midwest and South. In the early 20th century, the Tennessee River Valley marked a particularly devastated landscape in the Southeast. The constant flow of water combined with deforestation brought sediment and topsoil along with the river. Left in the wake was immense poverty and squalor, and a third of the population stricken with malaria. The land barely yielded any crops, but when it did, it was part of a quasi-feudal sharecropping system that kept poor black and white farmers alike in a kind of debt-peonage.

In 1933, amid a larger movement for public power against a profiteering private utility system, the Roosevelt Administration set up the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). While we often think of the TVA as a large-scale model of public power—an early slogan was “electricity for all”—we can forget how the TVA was about much more than power generation. It was a complex project of building state and public planning capacity geared toward rapid ecological restoration of the entire region.

At a basic level, the TVA engaged in large-scale land use planning: viewing the region as a mosaic with certain lands best directed toward specific purposes like flood control, forestry, and agricultural and residential settlement. The thorniest question was that some people and even their departed loved ones in graves had to be moved out of flooded regions. This process of resettlement, however, was addressed as a question of planning: assessing property values, interviewing families, offering “fair” compensation, and exploring different options. While this process was imperfect and sometimes unjust, it was surely more careful and systematic compared to the normal processes of market dispossession, foreclosure and other forms of private tyranny.

The Tennessee River itself was transformed into a coordinated machine geared toward flood control through a complex network of dams, locks, and reservoirs. With help from the young workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps, the agency embarked on a project of reforestation: planting trees that would also hold back the flood in times of highwater. The TVA not only produced a new kind of superphosphate fertilizer that could enrich the depleted river valley soil, it also enlisted armies of soil conservation experts who could visit and advise farmers on how to integrate cover cropping, crop rotation, and other soil enriching practices. Above all the TVA encouraged the valley to join a larger process of industrializing farming to be more efficient, save land and labor, and free many from toil.

The TVA brought power: loads of cheap abundant power to an impoverished rural region that lacked it. Its yardstick approach to electricity aimed to offer such cheap rates that private investor-owned utilities would have to adapt or perish. The TVA also encouraged new municipal utilities and rural electricity coops to form and contract for cheap TVA power, working in tandem with Harold Ickes’s Public Works Administration and the Rural Electrification Administration respectively.

For impoverished farmers, electrification was life changing. The drudgery of washing and ironing clothing, food preparation and storage, and water hauling, could all now be automated, freeing up labor and time for leisure. That leisure in turn had political consequences. The introduction of lighting and the radio helped open up isolated rural households to a larger world—including FDR’s fireside chats, which articulated a new vision of government service, planning and democracy.

■

Matt Huber is a professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at Syracuse University. He is the author of Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet.

Fred Stafford is a STEM professional and independent researcher on the Left.