Contemporary US-China Relations: A Primer

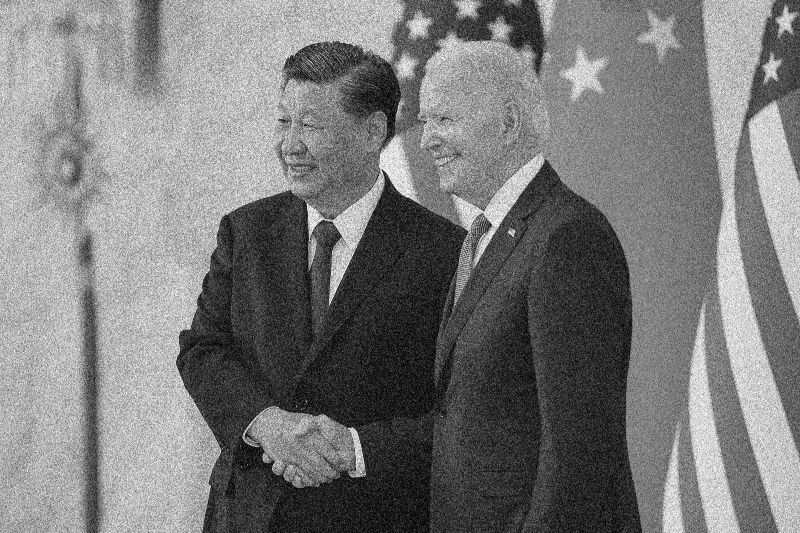

The Biden-Xi summit did not do much to repair the spiraling US-China relationship. What are the experts saying about how we got here?

The two most powerful men in the world, Joe Biden and Xi Jinping, just wrapped up a crucial diplomatic summit in San Francisco. Biden and Xi made important progress in the meeting, restoring direct military-to-military communications, addressing the fentanyl crisis, and setting limits on the use of AI in nuclear operations. However, no headway was made on major issues such as American technology export controls, growing Chinese aggression in the Taiwan Strait, and territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

US-China relations thus remain quite worrisome, with constant signs that we’re entering a new Cold War. As Xi correctly stated, the US-China relationship is “the most important bilateral relationship in the world.” A breakdown of this relationship could have catastrophic consequences. Many politicians, commentators, and scholars have offered explanations of this spiraling relationship. What are the experts saying about how we got here?

Washington and the Realists

The US government’s foreign policy strategy on China from the 1990s through the 2000s was one of “strategic engagement.” The American state, in its purported mission of spreading freedom and democracy around the globe, attempted to foster liberal values in authoritarian China. The US was well aware that trying to do so through extreme measures such as regime change was not on the table. But the economic reforms of the Deng Xiaoping era offered an opportunity for America’s democratizing mission. With the unshakeable belief that capitalism is politically compatible only with liberal democracy, the US saw fostering China’s reforms towards capitalism as the path to a free democratic China. Thus, it spent these decades pursuing a strategy of Wandel durch Handel (change through trade). In America’s view, promoting capitalist reform within China and bringing it into the neoliberal global free trade order would eventually lead to political reform that would transform China’s authoritarianism into a liberal democracy.

China’s intensifying authoritarianism shattered the faith in this project. With its ongoing repression of Uyghurs and Tibetans, aggressive actions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, and suppression of protesters in Hong Kong, Washington is now well aware that Wandel durch Handel was a dismal failure. The US thus shifted course to contain China and stop it from threatening the fair and free “international rules-based order.” In Washington’s view, the rise in US-China tensions is still about a clash of values between American democracy and Chinese autocracy.

Adherents of realism find this view somewhat absurd and offer an amoral interpretation based on the structural dynamics of great power politics. The most commonly cited explanation for worsening US-China relations is Graham Allison’s Thucydides’ Trap in Destined for War, a national bestseller that has been immensely influential in both academic and popular discourse. According to realists like Allison, a structural compulsion towards conflict emerges when a dominant incumbent power is faced with a new rising power. On one hand, the rising power is no longer satisfied with its subordinate place in the international order and seeks to revise it to better suit its needs. On the other hand, the incumbent hegemon feels threatened by the new rising power and attempts to contain it. In Thucydides’ time, the rising revisionist power was Athens, which challenged the incumbent Sparta. Today, the challenger is China; the current hegemon, the United States. With a dataset of sixteen case studies of rising vs. incumbent powers, Allison finds that twelve of them resulted in war. Despite his book’s title, however, he is not fatalistic about a US-China war and offers some advice on how that outcome could be avoided. However, the conditions that allowed for the avoidance of war in four of his case studies mostly do not apply to the US and China. In Allison’s view, then, the structural forces that are edging us towards war are more powerful than the counterforces.

The offensive realist John Mearsheimer, who has recently gained much currency on the Left due to his NATO-centric explanation for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, makes a very similar argument to Allison and is more explicit about the political implications of realist analysis. In Mearsheimer’s view, strategic engagement was a strategic blunder by the US because it allowed China to rise to great power status in the first place. Instead, the US should have begun to contain China once the Soviet threat had been eliminated. For Mearsheimer, the US’s current containment strategy of economic sanctions, export controls on US technology, and militarily strengthening Asian allies should have started back in the 1990’s. Washington’s failure to implement a hawkish strategy hastened China's rise and the end of the unipolar American moment. Now that China is a great power that can geopolitically rival the US, Washington has belatedly changed course to address the China threat—a change it should have made decades ago.

Mearsheimer’s account has one significant weakness. If the American state is willing to pursue a more realist strategy today, what explains its failure to do so for over two decades after the Soviet Union’s collapse? Mearsheimer has argued that Washington sincerely believed in Wandel durch Handel, but his own theory that political systems are irrelevant in great power competition—that great powers are forced into zero-sum competition by the rise of other great powers, regardless of whether they’re liberal democracies or Communist authoritarian states—would seem to invalidate this speculation. Thus, the very premises of realism contradict Mearsheimer’s explanation for Washington’s very un-realist 25-year policy of strategic engagement. All he can do is write it off as a mistake.

The CCP’s Capitalist Friends

Ho-Fung Hung, a frequent contributor to left publications such as New Left Review and Jacobin, doesn’t view the past friendliness of US-China engagement as a mere strategic mistake. In some ways, Hung is more of a realist than Mearsheimer. While Mearsheimer believes that the American state in the 1990’s simply blundered, Hung demonstrates that political elites in Washington actually were thinking in realist terms. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US no longer needed China as a strategic ally in the Cold War. Now that it had a new enemy in its sights, the “China threat” began to appear in American foreign policy discourse. Shortly after his inauguration in 1993, Clinton officially tied China’s free trade benefits to improvements in its domestic human rights abuses in an effort to cut China off from the vital US market.

Despite wanting to pursue a realist strategy, however, the US did not do so. Why? In Hung’s view, under the threat of American containment, the Chinese Communists enlisted the help of an unexpected ally: the American capitalist class. In order to maintain low-tariff access to the US market, the CCP organized American businesses to lobby Congress members on its behalf. It offered various forms of economic benefits to large corporations such as AT&T, Boeing, and GE, who in turn pushed Clinton and Congress to maintain free trade with China. This alliance of the CCP and American business succeeded, and Clinton delinked China’s free trade benefits from human rights requirements in May 1994. In other words, the ideology of Wandel durch Handel was an ex-post rationalization that let the US pursue profits in China while also remaining rhetorically committed to democratization.

In Hung’s view, then, the realists are correct that Washington was structurally impelled to pursue a containment strategy against the rising rival of China. However, this impulse was contained by the countervailing force of American business interests that wanted a stable relationship in order to pursue profitable opportunities in China. In other words, the prevailing peace between the US and China that lasted from the early 90’s into the 2010’s was a neoliberal peace: a pact between the Chinese state and American capitalists to collaborate in the pursuit of development and profits.

This neoliberal peace also dealt a devastating blow to the American working class. Organized labor lobbied to impose human rights requirements on China as a way of stopping untrammeled free trade between the two countries. The unions’ primary motivation wasn’t human rights, but rather the threat of losing union jobs to low-wage Chinese sweatshop labor. The unions lost this fight and their fears became reality. According to the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions, the “China shock” accounted for nearly 60% of US manufacturing job losses since 2001, and the most hard-hit areas have never recovered.

This Pax Economica has now come to an end. In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese government launched a massive program of monetary and fiscal stimulus that let the Chinese economy quickly bounce back. However, the hasty debt-fueled stimulus also created inefficient investments and a large debt overhang that has grown to gargantuan proportions. With economic challenges mounting, the party-state took a decisively statist turn against private companies and foreign businesses. Since this turn, the CCP has limited market access for foreign businesses and stolen foreign technology. While China used to provide favorable terms to foreign companies, it has increasingly set measures that favor Chinese domestic firms. With a worsening Chinese business climate for American firms, US corporations have lost interest in defending the CCP in Washington. And with the countervailing force of corporate lobbying gone, American political elites are finally free to pursue a hawkish anti-China realist strategy of containment.

China’s Hawkish Interest Groups

While Hung’s argument explains why the US became more hawkish towards China, it doesn’t address China’s own hawkish turn. For decades after the start of the Deng reforms, Chinese diplomacy was known for its amicability. Deng famously said that China should “hide our talent and bide our time” and “never seek leadership.” Deng set aside disputes in the South China Sea in order to promote better relations with Southeast Asia. Even with China’s hated enemy of Japan, Deng set aside the issue of the Senkaku Islands for later generations to figure out.

But in the mid-2000’s, Chinese foreign policy took an unexpected aggressive turn that has continued into the present day. Chinese diplomats, once known for their friendliness, began engaging in “wolf warrior diplomacy” and directly insulting other countries. Chinese state media began calling for military action in the South China Sea and the East China Sea, even calling for China to nuke Japan. Chinese propaganda, which had previously tried to contain anti-foreigner nationalism, began actively promoting anti-US sentiment.

While some leftists attempt to portray all of this unsavory foreign policy as defensive measures against the US, the timeline doesn’t support this explanation. China renewed military activity in the South China Sea and the East China Sea years before Obama’s 2011 Pivot to Asia, which itself had few concrete containment measures. The real American offensive of China containment did not begin until 2017 under the Trump presidency. In addition, seeing China’s hawkish foreign policy as a mere reflexive response to US policy fails to explain why China’s bilateral relations with many other countries have deteriorated.

Susan Shirk’s Overreach is one of the few books that opens the black box of Chinese domestic politics to explain the aggressive turn in China’s foreign policy. As one of very few Americans to visit China in the leadup to the famous 1972 Nixon-Mao meeting, Shirk has an unusually high degree of access to Chinese officials. Drawing from insider knowledge of the Chinese party-state, Shirk attributes the turn to both hawkish foreign policy and repressive domestic policy to the decentralization of the Hu Jintao administration. Having suffered the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping and other party elites began a process of decentralizing power to avoid another unilateral dictator like Mao. Deng’s political reforms changed the Chinese government from a dictatorship into an oligarchy, where major decisions required consensus amongst top CCP elites. With Xi Jinping’s return to one-man rule, many romanticize the good old days of collective leadership.

Shirk doesn’t take such a rosy view of the Hu administration’s collective leadership. For Shirk, collective leadership under Hu was not a process of consensus building, but rather a form of intense political fragmentation. Major decisions required unanimous consensus on the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s most important leadership body. But instead of genuine consensus building where leaders came to collective decisions with a view for what was best for China, political elites simply rubber-stamped each other’s proposals as a quid pro quo. As policy portfolios were divided amongst different elites, elites approved each other’s proposals with little concern for the bigger picture because they also wanted support for their own proposals. Thus, collective leadership was actually a form of siloing where elites separately managed their policy fiefdoms with little mutual oversight, creating a form of rubber-stamping that Shirk refers to as “log-rolling.”

With this analysis of the Hu period, Shirk explains not only China’s hawkish turn but also the mystery of why this hawkish turn began particularly in the South China Sea (SCS). Although territorial disagreements in the SCS had not been resolved, it was still a second-order issue in comparison to hot-button topics like Taiwan and Japan. But in 2006, China unexpectedly became far more aggressive in asserting its SCS claims, leading to conflict with its neighbors and the United States. According to Shirk, the SCS became the main site of China’s hawkish turn because various political groups’ interests converged in the SCS. The powerful state energy companies wanted to access the SCS’ rich natural gas and oil reserves. SCS conflicts gave the Navy an excuse to develop greater ship-building capacity. With China’s shores overfished, the Fisheries Department wanted to expand fishing into the SCS. The Propaganda Department used SCS disputes to foster nationalist sensationalism. Shirk dubs this alliance of interest groups the “control coalition.” The coalition had representation on the all-important Politburo Standing Committee and log-rolled their way into an aggressive policy in the SCS. The experienced diplomats of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs didn’t want to destroy China’s friendly relationships but had been sidelined with no representation on the Standing Committee.

China’s hawkish turn did not stop in the South China Sea. While the energy sector and Fisheries Department were less interested in areas outside the SCS, the more powerful members of the control coalition such as the Propaganda Department and the military wanted to continue pushing a hawkish foreign policy elsewhere. Deng bracketed China’s dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands, but Beijing reignited the issue and increased military activity in the East China Sea. China has steadily increased military activity in the Taiwan Strait since 2013 and called for the “reeducation” of Taiwanese people after unification. Chinese hawkishness did not stop in Asia either. When Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, China pressured foreign governments to boycott the award ceremony and unilaterally imposed economic sanctions on Norway (despite the fact that the Norwegian government doesn’t even select Nobel Prize winners). Chinese officials nearly canceled President Hu’s scheduled visit to Washington because they were convinced that Hillary Clinton was behind Liu’s Nobel Peace Prize. When Australia called for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid, China banned all Australian imports with the exception of crucially needed iron ore.

As the global policeman of the world, the US has been drawn into these conflicts. Facing growing Chinese hostility, China’s Asian neighbors drew closer to Washington and asked for military and political protection. Obama tried to steer a more moderate course, but the Trump administration fully gave into an anti-China policy, and the Biden administration continued it. Thus, Shirk sees China’s turn to hawkish foreign policy as the origin of US-China tensions, a turn that is explained by the parochial interests of specific Chinese bureaucracies operating in a fragmented state. Although Shirk believes that China was the first offender, she does not give a pass to the US either. China’s overreach has been matched by an American overreaction. In Shirk’s view, many US officials have erroneously concluded that China seeks to displace the US as the global hegemon. The export controls and visa restrictions that the US has levied on China have not only hurt America but also stoked anti-American sentiment in China. Despite China’s aggression, the US is far from blameless in heightening rising bilateral tensions.

While Shirk gives a powerful explanation for the beginnings of the hawkish turn under the Hu administration, she does not have a strong account of why this turn continued and intensified under Xi Jinping. As she notes, Xi has centralized power. The days of the control coalition being able to pursue their parochial interests untrammeled are over. While Chinese governance is still quite decentralized in many ways, Xi could steer China towards a more dovish course if he wanted. Shirk seems to believe that China’s continued hawkishness is due to Xi’s political preferences and an echo chamber that excludes negative feedback, but this argument lacks the strength of the structural account she provides of the Hu era.

While China experts have different analyses of deteriorating US-China relations, all of them agree on one point: diplomacy is essential for avoiding a disastrous war. There might be powerful structural forces behind ratcheting tensions, but the agency of political leaders would be the ultimate determinant in any potential war. War would be a mutually destructive event in which both sides might not survive. While more could have been accomplished at yesterday’s summit, the moderate progress is a hopeful sign that Biden and Xi are aware that dialogue is worth the effort.

■

Kevin Zhang is an independent researcher.