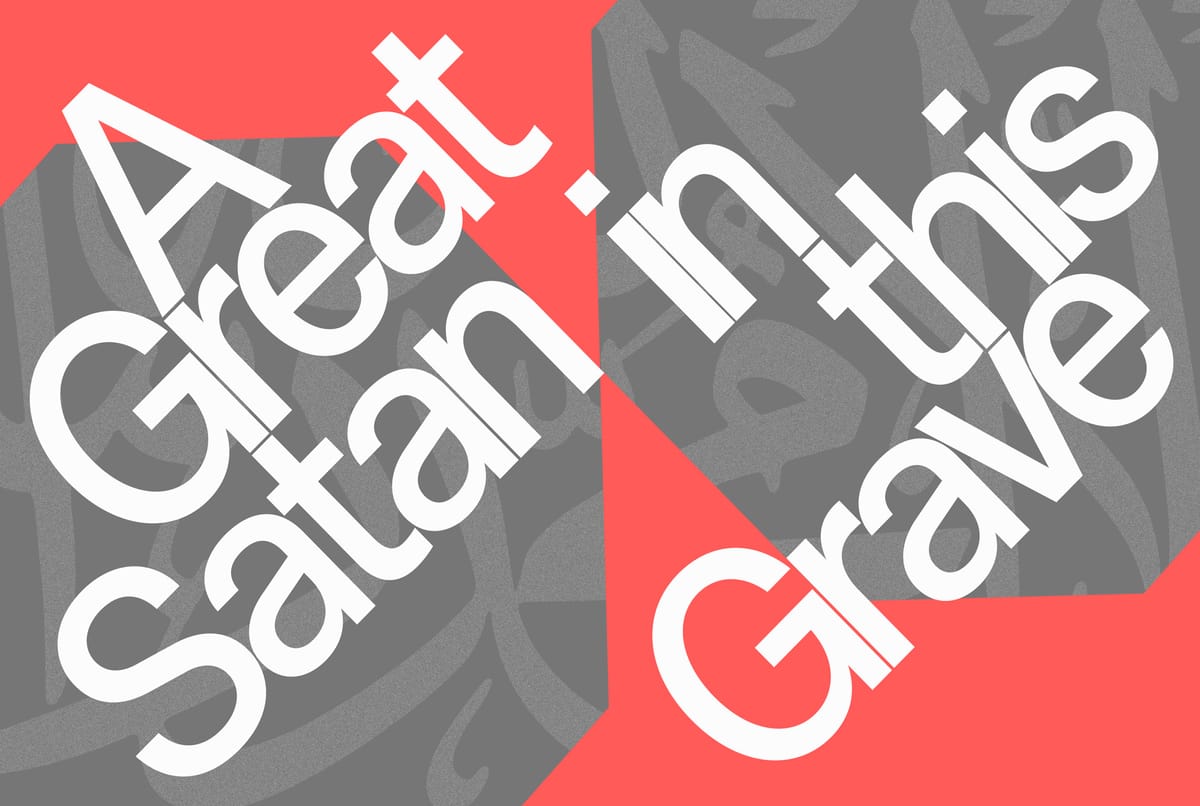

A Great Satan in this Grave

Why is Saudi Arabia, possibly the worst and most repressive country in the world, also the only place still keeping the modernist ethos alive?

In the late eighteenth century, the Ottoman authorities placed an enormous fort on Bulbul Mountain, a hill in Mecca directly overlooking the Kaaba. According to tradition, the Kaaba is a replica of the Bait-ul Ma’mur, the house of God, which is visited by seventy thousand angels in constant prayer. It’s a kind of earthly shadow of its holiness, positioned directly beneath it: the two structures face each other, with the Kaaba facing up and the Bait-ul Ma’mur facing down. This is the place where the earth touches closest to heaven. (Directly above the Bait-ul Ma’mur is the throne of God himself.) Then, in between the two, there was this squat stone military fortress. You couldn’t make one rotation around the shrine without seeing it, perched on its bald hill, watching.

A kind of sacrilege, but maybe a necessary one: the peninsula was about to collapse into war. Fanatical Bedouin tribes poured out of the desert to attack the caravans, sack the cities, destroy every sacred site in reach, and commit terrible massacres. In 1802, they pillaged the holy city of Karbala in Iraq, razed its mosques, and killed some five thousand of its people. In 1805, despite the new fort, they captured Mecca and Medina. That capture was followed by a wave of intense vandalism. In Medina, they desecrated the al-Baqi cemetery, where Mohammed had buried his infant son Ibrahim. In Mecca, they smashed the grave of Khadijah, his first wife, and tried to destroy the tomb of the Prophet himself. In the few years they held the city, almost everything that had survived the centuries since Mohammed was pulled down. They seemed to want to destroy Islam entirely, to wipe the religion off the face of the earth. The Ottoman officer (and propagandist) Ayyub Sabri Pasha described their attack on the city of Taif:

They killed every woman, man and child they saw, cutting even the babies in cradles. The streets turned into floods of blood. They raided the houses and plundered everywhere, attacking outrageously and madly till sunset.... They tore up the copies of the Qur’an and books of tafsir, hadith and other Islamic books they took from libraries, masjids and houses, and threw them down on the ground. They made sandals from the gold-gilded leather covers of the Qur’an and other books and wore them on their filthy feet. There were ayats and other sacred writings on those leather covers. The leaves of those valuable books thrown around were so numerous that there was no space to step in the streets.... When they attempted to dig a grave with a view to take out and burn the corpse of Ibn Abbas, who was one of our Prophet’s most beloved companions, they were frightened by the pleasant scent that came out when the first pickaxe hit the ground. They said, “There is a great Satan in this grave. We should blow it up instead of losing time by digging.”

Those bandits belonged to the Emirate of Diriyah, a backwater chiefdom that had suddenly grown to take over half of Arabia. Today, it’s also known as the First Saudi State.

The Third Saudi State—the one we have now—has kept up this tradition. Khadijah’s house is now a block of public toilets. The house of Abu Bakr, the first Sunni Caliph, is now a Hilton hotel and a Burger King. A small mosque raised by Abu Bakr has been replaced with an ATM. The house where Mohammed was born was first bulldozed to be turned into a cattle market, and then a library; now there are plans to demolish the library and put up a presidential palace instead. The sites of battles fought by the first Muslims have been filled in with concrete. Finally, they destroyed the Ajyad Fortress, the castle on Mount Bulbul overlooking the Kaaba, along with the hill itself. In its place, there stands the Abraj Al Bait, currently the fourth-tallest building in the world.

It might be wrong to say that the Abraj al Bait is in Mecca. The thing seems so much bigger than the city that contains it, like a real skyscraper plopped into a model village. Everything about the thing is superlative. It is nearly two thousand feet tall, forty-six times taller than the Kaaba that shivers in its shadow. Its central tower is crowned with a crescent seventy-five feet high and weighing thirty-five tons, made from mosaic gold backed with fiberglass. Speakers at the top of the building broadcast the call to prayer, accompanied by twenty-one thousand flashing white and green lights, for twenty miles. Its foothills hide a five-story shopping mall with four thousand stores. There are seven hotels in the complex, including a Raffles, two Swissotels, and the Fairmont Royal Tower. The building is plastered in an almost inhumanly tacky combination of neoclassical stone and 2010s green glass. Each face of the central tower contains an enormous clock, forty-six meters in diameter, finished with forty-six thousand square meters of mosaic, or ninety-eight million individual tiles. The carbon-fiber hands alone weigh twelve tons. For a while, there were proposals for Mecca to replace Greenwich as the prime meridian, based on the reasonable argument that time should belong to whoever has the biggest clock.

It was built, of course, by the Saudi Binladin Group, the peninsula’s largest construction conglomerate, which has put up enormous skyscrapers across the Middle East—but which is still best known, in the West, for the time one of its rogue scions took two of them down. Mohammed Atta studied for a Master’s degree in city planning at the Hamburg University of Technology. He wrote his thesis on the disruptive and alienating effects of large buildings: “The traditional structures of the society in all areas should be re-erected.” It’s not impossible to read his subsequent activities as a particularly gruesome exercise in architectural criticism.

But maybe the 9/11 hijackers were simply not devout enough. There’s a strain in Islamic philosophy—most prominently, that of the ninth-century Sunni theologian Abu Hasan al-Ash’ari—influenced by the doctrine of occasionalism. Occasionalism posits that there are no secondary or proximate causes: everything that happens, happens directly because of God. If you put a torch to a stack of holy books and they burst into flames, you did not cause that, because you are powerless and can cause nothing. God made the books burn, not the torch: as the Qur’an puts it, “God created all things, and He is the agent on which all things depend.” In the strongest version of occasionalism, there is not only no such thing as cause and effect; there’s no such thing as time. God creates the world, but because He is outside of it, it immediately crumbles into nothingness, and so He creates it again. What we see as movement—your hand waving, a motorbike speeding down the road in front of you—is just God recreating your hand and the motorbike in a succession of minutely different positions, and unimaginable eternities might pass in the cracks between each instant.

In Shi’a Islam, the past swallows everything. “Every day is Ashura and every land is Karbala.” We are still in the year 941 AD, waiting for the last imam to come out of occultation, so that real time can resume. But for a certain kind of Sunni Islam, the past simply does not exist. Graveyards in Saudi Arabia are desolate places, broad and pitiless, with each grave marked only by a single, undifferentiated lump of rock: the bones here are just bones, with no relation to any persons living or dead. The last vestiges of premodern architecture in Mecca are not actually any older than the fast-food restaurant around the corner. Maybe this is why Saudi Arabia is the last truly modern place left in the world, the last place committed to the idea of making things new.

Lines, Octagons, Cubes

The Abraj al Bait was only the start. Maybe you’ve already seen some of what the Saudi government is intending to build next: they’ve spent an extraordinary amount of money advertising it across the world. For a while, I couldn’t so much as glance at a screen without being shown images and videos of the Line, an entire city under construction near the Red Sea. Although the Line is less a city than a single, enormous megastructure: taller than the Empire State Building, slightly narrower than a single block in New York City, and about as long, east to west, as Portugal. Videos show this thing cutting a mirrored-glass scar one hundred miles into the desert interior. It looks like the most ridiculous and impossible project ever conceived.

According to the Saudis, the Line “is a civilizational revolution that puts humans first, providing an unprecedented urban living experience while preserving the surrounding nature. It redefines the concept of urban development and what cities of the future should look like.” Cities of the future should, apparently, look like an enormous toothpick. The city will have no roads and no cars, but high-speed trains will shuttle from one end to the other in twenty minutes. (This would require the trains to move at 300 miles per hour, including stops. The Shanghai Maglev, currently the world’s fastest passenger train, has a top cruising speed of 268 miles per hour.) In the middle of one of the world’s hottest deserts, its climate will be controlled entirely through ventilation and passive cooling. All its services will be delivered by a vast omniscient AI that knows what you want before you do. Its radical linear shape and half-kilometer height means that the entire city will only occupy thirteen square miles of land—in a country whose one truly inexhaustible resource is its vast tracts of empty space. All its water will come from desalination, and all its energy will come from renewable sources—in a country whose other major resource is vast quantities of oil. And it will, according to its promoters, be inhabited by nine million white entrepreneurs and creatives and people of tomorrow, living in the apogee of mixed-use high-density walkable urbanism in the successor state to the brutal Emirate of Diriyah.

There’s a reason most cities tend to be vague, splotchy circles, rather than perfectly straight lines. In a vague splotchy circle, you can have a central services hub that’s equally accessible to everyone, with smaller local centers built around it in a way that efficiently uses all the available space. In a line, you live in a baffling and pointless plank. In a city that is not just a single straight line, there’s usually a good amount of redundancy built into the transport system: if one road is blocked off, you can always take another. In a city that is just a single straight line, if absolutely anything goes wrong—say, a brief signal failure somewhere in the middle—the two halves of the city are entirely cut off from each other. This is not good urban planning, and it’s very easy to imagine how The Line will fail.

It would be a dark, gloomy, moist, fetid place. The desert winds would heap an enormous bank of sand against its mirrored façades: the place would feel subterranean, walls closing in, a bunker in the wilderness. If your windows look out on to the central atrium, you’d get maybe a few minutes of sunlight every day: enough to see the piles of garbage filling up its voids, the bullet holes and body parts in the windows on the other side. They say that there are parts of this city, miles from anywhere in the middle of the desert, where the water still runs and the authorities are still in charge, but you can’t get there. Mobs of former graphic designers and biotech consultants pile wreckage in the mass-transit tunnels to seal off their fiefdoms. At night, the jackals scream. Once all its residents have eaten each other, the creatures of the desert will reclaim this place. Snakes will make their burrows in its exciting vertically stacked neighborhoods, and lick the moist air, unblinking.

But the most common response to the Line is to simply argue that this is a pipe dream, a PR project, a publicity stunt, a way of shifting attention away from the Saudi government’s murderous war in Yemen and its habit of removing dissidents’ heads with swords or dismembering them inside its embassies. The thing is too ridiculous to exist. It depends on trains that haven’t been invented yet and desalination technology that also doesn’t exist. It will never actually happen.

The pipe dream criticism makes a lot of sense. What makes less sense is that the Line is, in fact, happening. The state has put aside $1 trillion for the project, and construction has already begun. Drone footage shows excavators digging out an enormous trench in the desert. Satellite photos show the pale impression of a single, monstrously straight line churning through the rock. And the people who need to be killed to make this thing a reality are already being killed. The Howeitat tribe have inhabited the area for centuries; now, they’re being forcibly moved off their land. In April last year, Abdul-Rahim al-Howeiti, a tribal activist who refused to leave his home, was shot dead on the street by Saudi security forces. “I don’t want compensation,” he said. “I don’t want anything. I only want my home.” He won’t be the last to be cleared out. Thousands more people will die in the steel and scaffolding as this giant minus sign rises out of the earth, and almost nobody will ever know their names.

The Line is only one of the monstrosities that the House of Saud are raising in their desert. It forms part of a superproject called NEOM. This project will also include a new industrial city called Oxagon, which will be the world’s largest floating structure: an octagon-shaped maze of warehouses and biotech labs bobbing pointlessly on the Red Sea, like Venice but for the pharma industry. Why does it need to be on the water when there’s a surfeit of dry land available? Not clear! In the hills, meanwhile, there’s Trojena, a mountain resort that will offer the world’s largest artificial lake, cantilevered thrillingly off the cliffsides, in a desert whose temperatures regularly reach over 100° Fahrenheit, along with year-round outdoor skiing, again in a desert whose temperatures regularly reach over 100° Fahrenheit. Trojena will host wellness summits, yoga retreats, and, according to its website, “alternative medicine,” along with the 2029 Asian Winter Games. It also features a “folded vertical village” called “The Vault,” a kind of glittering chrome science-fiction vagina cut into the hillsides, that will form “a portal connecting the digital and the physical.”

Finally, in Riyadh, the Saudi government has announced plans for the Mukaab, an enormous golden cube 1,300 feet tall. Inside this cube there will be an enormous dome, and inside the dome there will be another skyscraper, packed with retail and entertainment. The centerpiece of this architectural turducken is the dome itself, whose entire inner surface will be covered in a seamless high-definition display. Sometimes, walking around inside the Mukaab will be like a trip to the deep oceans, with extinct whales coiling around the luxury shopping outlets. Sometimes it will transport you to the surface of Mars. Sometimes there will be dragons. The screen alone would consume roughly as much electricity as a small American city.

Things with a Shape

All these ideas are ridiculous. But they are not, in fact, as new as they seem.

The first version of the Line was envisaged by the Spanish architect Arturo Soria y Mata at the end of the nineteenth century. His Ciudad Lineal was designed as a long ribbon snaking away from Madrid, two blocks wide and segmented like an enormous millipede. At the center, a railway line would speed goods and passengers from one end of the strip to the other. Homes and factories would surround it, and the whole structure would be dotted with technical institutes and houses of culture. When the city filled up, instead of falling prey to overcrowding and disease, it would just extend itself further into the countryside. The perfect city, Soria wrote, would be “a single street unit 500 meters broad, extending if necessary from Cádiz to St. Petersburg, from Peking to Brussels.” The trans-European metropolis was never realized, but the first part of Soria’s utopia was. Today, Ciudad Lineal is a neighborhood in the northeast of Madrid, not too far from the city center. It’s arranged around a long, snaking ribbon of a central highway, calle de Arturo Soria, named after the genius who inspired it. The tram that shuttled back and forth along that highway closed in 1972.

There were plenty of other attempts to resurrect Soria’s vision: both the United States and the Soviet Union once contained the detritus of half-built city-spindles ploughing through the landscape. The concept fed into Le Corbusier’s unbuilt Ville Radieuse, and a version of Soria’s line was adapted into Lúcio Costa’s initial design for Brasilia. But what really distinguishes the contemporary Saudi megaprojects is not so much this particular form, but the obsessive focus on form as such. Lines and octagons and cubes; an obsession with the geometry of life. The idea that a city ought to be a thing with a shape.

For a very long time, human settlements did have a shape. Claude Lévi-Strauss, visiting the Bororo, noticed that “their wise men have worked out an impressive cosmology and embodied it in the plan of the villages and the layout of the dwellings.” Each settlement is split in half, to represent the two social moieties; houses for the different clans are arranged radially, like the hours of a clock, with clusters for subclans, social classes, minute social grades. Because every group within the society has its own totems, colors, and stars in the sky, the layout of the village becomes a map of the entire universe and everything in it. Every Roman city was on an identical plan, center dominated by two major streets: the cardo, running from north to south, and the decumanus, running from east to west. The forum would be placed at their crossroads. Cardo means heart: this is a city on the plan of the human body. Decumanus refers to the organization of a Roman military camp: this is a city that models itself on the highly organized and militarized state. The Roman city marks the point where biological and political life come together. It is also a kind of geometrical model of reality.

Medieval cities have their shapes too, even if their streets were less formally laid out: quarters for different religions or trades, the notion that different forms of human experience can be expressed geographically. Renaissance visionaries like Filarete designed cities informed by esoteric geometry and astrological signs. (The Saudi Oxagon is an echo of the nine-sided city of Palmanova, built by the Venetians in 1593.) It was only with industrial modernity that all these forms started to break down entirely: the sudden swelling of slums, the factories blossoming according to the fungal plan of price and expediency. You end up with the London described by Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England:

The very turmoil of the streets has something repulsive, something against which human nature rebels. The hundreds of thousands of all classes and ranks crowding past each other, are they not all human beings with the same qualities and powers, and with the same interest in being happy? And have they not, in the end, to seek happiness in the same way, by the same means? And still they crowd by one another as though they had nothing in common, nothing to do with one another, and their only agreement is the tacit one, that each keep to his own side of the pavement, so as not to delay the opposing streams of the crowd, while it occurs to no man to honor another with so much as a glance. The dissolution of mankind into monads, of which each one has a separate principle, the world of atoms, is here carried out to its utmost extreme.

The project of modernism was, in a sense, a very retrograde one: to return the human environment to how it had been before modernity. The world can form a rational whole again; the places we build can express something about ourselves, other than our powerlessness. We can decide what shape our lives ought to take. We do not have to be slaves to practicality. There was a capitalist version of this principle—all those mathematically organized company towns across industrial Britain, cultivating good Protestant virtues through the hygienic arrangement of roads and cottages. But it could also have an emancipatory and revolutionary character. The earliest years of the Soviet Union were full of strange, unrealized experiments in form. Vladimir Tatlin’s rotating sculptural buildings; Georgy Krutikov’s flying cities suspended in the air. A new and different way of life, they understood, would have to come in new and different shapes.

This is not to say that any of these forms would actually work. Brasilia’s design was a utopian dream in form; it couldn’t make space for the messy contingencies of actual city life. Residents complain that the place is sterile, asocial; most of them have abandoned Costa’s highly planned city core for the more intimate suburbs. There’s a direct line between the early Soviet futurists and the postwar Japanese Metabolism movement, which did produce one completed project: Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo. The tower consisted of two concrete pillars, to which standardized and prefabricated pods could be attached by crane. The idea was that this building would change to reflect the new kinds of life being lived there. Maybe you start off living alone in a single pod. You meet someone else in the same building and fall in love. Eventually you decide to move your pods together. You start a family, and bolt a few more pods onto your home. A piece of the city that could move and breathe like a human body. But moving the pods around turned out to be impractically expensive, so most people just stayed in their own tiny cubbies, and the place became a slum. When I visited in 2016, the building was fenced off and rotting. The paper blinds that once decorated the pods’ portholes had long disintegrated; the remaining residents now just pasted newspaper over their windows. Some of the pods were still used as self-storage units. Most were empty. Last year, the building was torn down.

Still, I think something important is lost when we abandon all these mad experiments in form. If the variety of forms is an expression of the plasticity of human life, it’s significant that so much of what we build today in the West is so utterly formless. Blobby retail zones, sprawling shapeless suburbs: a limper, more amoebalike turmoil than anything in the industrial era. In America, there’s a single shape that proliferates like a yeast infection across the country: the “5-over-1” building, consisting of five wood-framed stories of poky apartments over a concrete podium, all wrapped up in plastic cladding. In every city these gray “luxury” blocks are as inescapable and as identical as the Soviet Union’s khrushchevkas. The universality of this form doesn’t even point to any universal approach to how life ought to be lived: it’s a pure figment of the U.S.’s fire safety codes. This shape gives you the highest density of residential units for the lowest investment while still being technically legal. That’s it.

To see just how much we’ve lost in a fairly short period of time, all you need to do is take a walk along the Thames. Thirty years ago, Bankside Power Station—a dark, hulking, oil-burning heap just across the river from the City of London—was slated for redevelopment. It ended up becoming the Tate Modern, the most-visited modern art gallery in the world. Last year, and just up the river, the newly refurbished Battersea Power Station—huger, more hulking, but once powered by coal—was opened to the public. One proposal, from Rafael Viñoly Architects, called for the power station to generate electricity again—this time, by encasing the site in an enormous dome topped with a thousand-foot-tall glass chimney, which would produce electricity by constantly drawing air upwards. It was ludicrous and probably not nearly as feasible as it pretended to be, but it had ambition. This was not the design we ended up with. Instead, the power station has been turned into a shopping center and some luxury apartments.

Today, there’s almost nothing left to challenge this tedium. The most prominent countervailing movement in architecture is an equally sterile traditionalism. More sophisticated versions are basically just Mohammed Atta-ism. “The traditional structures of the society in all areas should be re-erected.” We tried imaginatively recreating the urban form, and the result made us feel uneasy, so let’s just go back to narrow streets, slums, and impotence dressed up in the lumpy cloak of tradition. The less sophisticated advocates don’t even consider form at all: they just want their 5-over-1 apartment buildings to be dressed up in fake Roman columns or fake Gothic tracery. The vernacular of a society that has lost its imagination.

There’s only one place in which the modernist ethos is still alive. The Promethean ambition, the sense that human beings can be liberated from necessity and practicality, the transformation of life through new, deliberate, extravagant forms. And it’s Saudi Arabia—possibly the worst and most repressive country in the world. How?

What Is A Saudi Arabia For?

Maybe it wouldn’t be entirely correct to call Saudi Arabia a country. This place does not work like any other country that exists. For one, it does not, strictly speaking, have any laws. It’s not uncommon for Muslim countries to have legal systems based on Sharia, but in Saudi Arabia Sharia is the law, uncodified anywhere except in the Qur’an. Despite government efforts, the Saudi citizenry is still a basically negligible factor in the country’s workforce: everything from construction and resource extraction to service and technical work is carried out by a vast and disposable migrant population, while the Saudis themselves are content to do very little except have one of the world’s highest rates of obesity. Not so much a national project as an enormous workhouse. This place doesn’t even have an actual name. There were once named regions in this patch of land: Nejd, Hejaz. But Saudi Arabia just means that this is the portion of Arabia that was conquered by Ibn Saud. A piece of stolen property, marked with the name of its thief.

There are only a few other countries that don’t have their own name. Sliced-off nubs of geography like East Timor or South Sudan. And the United States of America.

In 1974, in the aftermath of Nixon’s unilateral dismembering of the Bretton Woods system, U.S. Treasury Secretary William Simon made a secret pilgrimage to Riyadh to hash out a deal with his Saudi counterparts. The United States would permanently assure the security of the House of Saud and its obese and feebleminded princelings. In return, the Saudis would only sell oil denominated in dollars, and they would invest the proceeds in U.S. Treasury bonds. Instead of a global reserve currency backed by gold, the dollar would be a global reserve currency backed by Saudi hydrocarbons. (The point wasn’t to secure Saudi oil for America itself, which has never been particularly dependent on Middle Eastern oil, but to make sure that everyone else needed a ready supply of dollars to keep their manufacturers going.) In effect, the world would have two financial centers: one in Washington, and a secret, shadow nexus in the desert; between them, they would jointly administer the earth.

In a way, this wasn’t just an economic arrangement. It marked the union of liberalism and Wahhabism, the two great modernizing traditions of the eighteenth century, both of which promised, by faith or by reason, to liberate humans from history.

But this strange arrangement—in which the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques could tear down dozens of the holiest mosques under his care, while letting a Swissotel tower over the Kaaba—is breaking down. It’s not just that liberalism has exhausted its emancipatory powers. It’s not even the more prosaic developments, like China’s repeated attempts to buy Saudi oil in yuan rather than dollars. (Despite all the rumors and public flirting, these efforts have so far failed to produce any actual yuan-denominated trades.) What’s changed is that the Saudis are now forced to plan for a world after oil. For hundreds of years, the Bedouin tribes that terrified the Ottomans had sat on some of the world’s largest energy reserves without knowing it. A sheer accident of history meant that the head-chopping descendants of the head-chopping Emirate of Diriyah managed to hold the shadow of the Bait-ul Ma’mur and the cornerstone of the entire planet’s economy at the same time. That conjuncture kept the Third Saudi State afloat for most of the twentieth century. It is also incidentally in the process of making large swathes of the planet uninhabitable. But now, as the world stumbles towards decarbonization, it’s breaking apart.

Saudi Arabia is a country that barely existed to begin with; at long last, it has to decide what it wants to be. What does this monstrous state look like after oil? This brutal and repressive society is facing the crisis of human freedom on a grand scale. They are confronted with the capacity to be anything, unbound to any past. But five thousand years ago, in the same corner of the world, there was a similar crisis, and a similar solution. “And they said one to another, Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Come, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.”

■

Sam Kriss is a writer and dilettante in London.