What's in Our Second Print Issue, “Deinstitutionalized”

What does it mean to live in a deinstitutionalized society today, and why do contemporary institutions so often fail to make up for what has been lost? Our second print issue, “Deinstitutionalized,” seeks to find out.

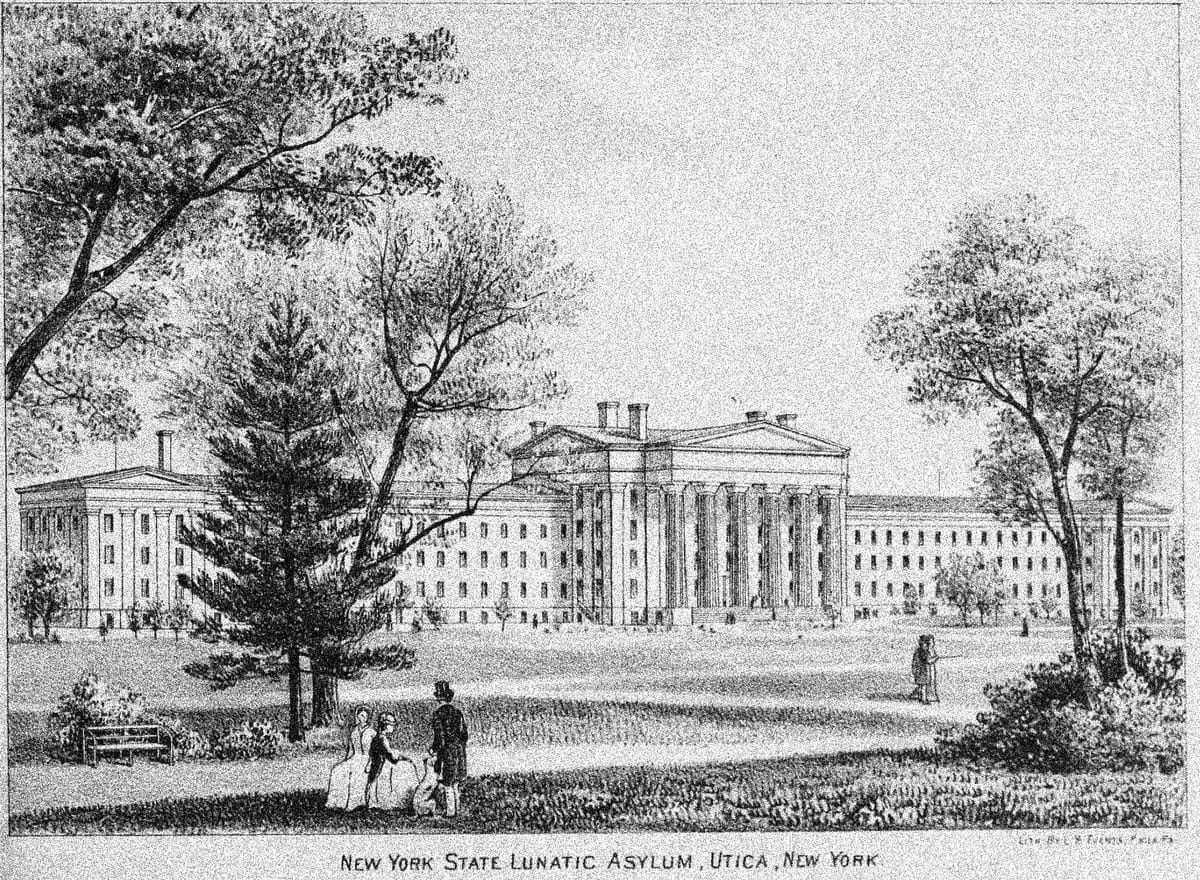

“Deinstitutionalization” describes a process, begun in the mid-twentieth century, when large, publicly funded psychiatric hospitals were shuttered in favor of smaller community care facilities or family care for treatment of the mentally ill. With the image of Nurse Ratched from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in mind, the hope was to eliminate a terrifying form of inhumane control, one made possible by the large state bureaucracies of the twentieth century. When these institutions closed, however, nothing came along to replace them, and today many people with severe mental illness are on the street, in prison, or in the care of their families. According to historian of psychiatry Andrew Scull, who is interviewed for this issue,

despite all the rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic about ‘better services for the mentally handicapped’..., the reality was the much darker one of retrenchment or even elimination of state-supported programmes for victims of severe and chronic forms of mental disorder. Community care was a shell game with no pea.

While we will spend a little time in this issue on this marked transformation in the care of the mentally ill, we mainly wish to explore the broader resonances of the term “deinstitutionalization.” Institutions serve grounding functions; they are the foundations of established practices. In the mid-twentieth century, a variety of institutions ordered society, for good and for bad, and with their collapse, both social and political life have become chaotic and fragile. Today we take for granted that things have melted into air, with little experience of them having once been solid. What does it mean to have deinstitutionalized socially?

At the same time, new institutions have come to fill the void, but they seem like pale reflections of the older ones—hollow, unrepresentative, fragmented, improvised, insulated. If the old fears about institutions circled around the possibility of total social control, today they do so around social negligence. In this sense, they lack the traditional grounding function and instead serve as protective barriers against popular pressure.

In the issue’s opening interview, Andrew Scull reviews the history of asylums and how we ought to understand these fraught institutions today. As Scull notes, in the absence of such institutions, many people who were once warehoused in such places are now a burden on their families, in prison, or on the streets. In “Making the Present the Enemy of the Future,” Dustin Guastella critiques one form of response to this new situation: that of decriminalization or harm reduction, specifically as applied to the case of Kensington Avenue in Philadelphia. For Guastella, decriminalization is the latest iteration of libertarian/liberal policies that are destroying American cities, one that is making “the case for establishing or expanding public rehabilitation services much more difficult.”

One might see both increasing drug use and the hands-off approach of harm reduction as expressions of a broader disengagement, the subject of Alex Hochuli’s “From ADHD to Let Me Be.” Hochuli surveys different forms of contemporary disengagement that feed on frenetic forms of reactive “engagement” that defined the recent populist moment and finds them all strangely bound to the lowered prospects of the present. He advocates instead a politics of time which aims to create a “society in which people are free to determine for themselves what they do with the finite time of their lives, sustained by institutions of mutual recognition.”

Paul Prescod and Catherine Liu then take on two academic shibboleths today: the privileged lens of “institutional racism” and the cultural studies turn. Prescod argues that the rhetorical framework of institutional racism, a flawed framework for understanding inequality when it was first introduced, today obfuscates “the causal factors of… inequalities in the modern neoliberal era, and doesn’t adequately take into account the changes in black social and political life that have taken place since the civil rights movement.” Liu meanwhile finds the cultural studies revolution in institutions of higher education to have been, in retrospect, “strangely consonant with the broader restructuring of the neoliberal university.”

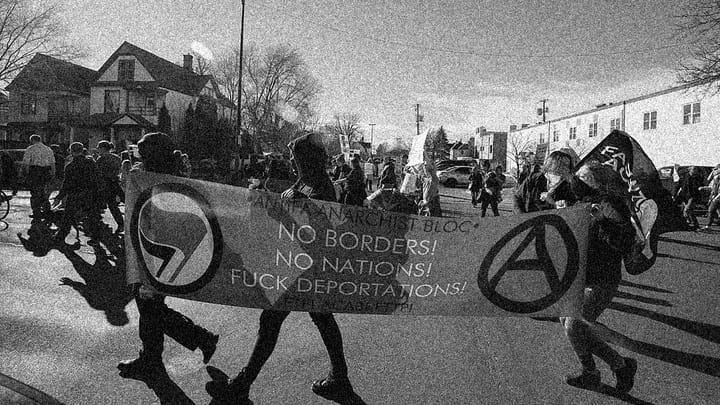

The next set of articles look more closely at institutional decline. Matt Huber and Fred Stafford examine the effects of the deregulation of large electrical utilities. Despite the climate Left’s general support for this transformation, Huber and Stafford argue that it has hampered our ability to engage in the broad-scale infrastructural change needed to address the climate crisis. Taylor Hines then tells the tale of the rise and fall of Robert’s Rules of Order as a governing code for large assemblies. Hines believes the present animosity often expressed toward Robert’s Rules is a reflection of the changing composition and function of organizations today. Finally, Benjamin Y. Fong looks at the decline of associational life in the United States through the lens of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. America stopped being a country of joiners in the neoliberal period, but, remarkably, fraternal organizations persist today, and some even have great hopes for them.

Amber A’Lee Frost, Melissa Naschek, and the team of Matthew Thompson, George Hoare, and Jonny Gordon-Farleigh close out the issue on the new kinds of para-institutions that have cropped up in the neoliberal period. Frost dissects the Apple Genius Bar experience. Naschek takes a look at AARP, the senior rights advocacy organization whose contradictory incentives and lack of a representative membership structure push it to undermine a key program of senior support, Medicare. Thompson and company finally explore the form of the so-called “third sector” (NGOs, nonprofits, foundations, etc.), specifically through the case of the Participatory City project in east London. “The NGO,” they contend, “is the central para-institution of our age, simulating participation while preventing any meaningful public form of it.”

In many ways, “Deinstitutionalized” was a natural successor theme to that of our first print issue, “Building Big Things.” If our inaugural issue was about recapturing the dream of big infrastructural and organizational change in a moment of truncated and depressing political horizons, our second issue is about the various declines and dysfunctionalities that make that dream seem impossible.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong is the author of Quick Fixes: Drugs in America from Prohibition to the 21st Century Binge (Verso, 2023) and the producer/host of Organize the Unorganized: The Rise of the CIO.