The Passing of the American Century and the Cold Comfort of the Serial Killer

The rise of the serial killer was the dark side of the American twentieth century. Portrayals of serial killers today paradoxically evince a nostalgia for an age that was not as destructively nihilistic as our own.

The twentieth century saw the rise of America from a postcolonial rival to the British dominance of world capitalism to the undisputed global hegemon. It was decisively the American century. As the United States established economic dominance, it also exerted tremendous influence in the domain of culture across the globe. So it was that the twentieth century saw the increasing universalization of world culture in the American model, from McDonald’s to Hollywood cinema to rock and pop music. The bourgeois aim of creating a world after its own image was only possible in the twentieth century, and only possible for the American bourgeoisie.

But the American century had its darker side. Looking back from our vantage point in the early twenty-first century, the pathologies of the postwar American cultural and social model are increasingly clear. The serial killer Joel Rifkin, who murdered 17 women, believed he had a particularly American disease. In an interview with the New York Daily News in 2010, he claimed that “America breeds serial killers. You don’t see them in Europe.”

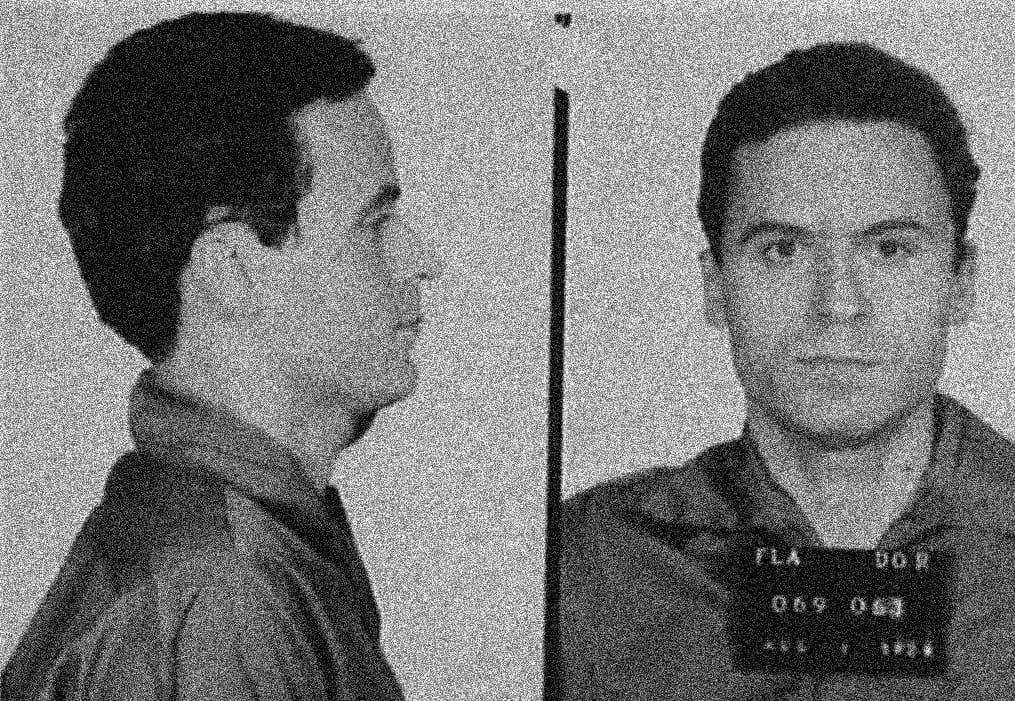

While Rifkin was not completely accurate, as European serial killers do exist, the serial killer was and is predominantly an American phenomenon. It is also one that, historically speaking, peaked in the 1970s and 1980s. Since the year 1900, roughly two thirds of serial killers have been American (and only around a tenth women), with a sharp decline in serial killings since the morbid peak of the 1980s. While serial murders—particularly of women—still happen, the decline over the past forty years has been precipitous. The drop in number of active serial killers—generally attributed to a combination of better detection by law enforcement, the use of DNA evidence, and a safer society that no longer condones hitchhiking—is sufficient to conclude that the age of the serial killer has passed, hopefully never to return.

And yet, the serial killer still plays an outsized role in our popular culture, which is now a reflection of an America on its way down rather than up. Part of the appeal of the serial killer lies in the wider attraction of the portrayal of those who violate society’s most inviolable rules. Murder is the ultimate moral crime. The more ingrained and widely-accepted this social rule against murder becomes, the more that we might turn to books, television shows, films, podcasts, comic books, police procedurals, and the like to experience the frisson of excitement we get from closer proximity to this ultimate transgression.

To better understand the American macabre, it might help to review a particularly English conception of murder, as represented by George Orwell:

It is Sunday afternoon, preferably before the war. The wife is already asleep in the armchair, and the children have been sent out for a nice long walk. You put your feet up on the sofa, settle your spectacles on your nose, and open the News of the World. Roast beef and Yorkshire, or roast pork and apple sauce, followed up by suet pudding and driven home, as it were, by a cup of mahogany-brown tea, have put you in just the right mood. Your pipe is drawing sweetly, the sofa cushions are soft underneath you, the fire is well alight, the air is warm and stagnant. In these blissful circumstances, what is it that you want to read about? Naturally, about a murder.

For Orwell, the ideal murderer is respectably middle class, with a clear motive of sex or inheritance; in other words, a character in a Poirot mystery. This ideal is really dated to the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth. The serial killer, by contrast, represents a decisive step away from Orwell’s analysis or the “cosy crime” of Agatha Christie. Instead of the unmistakably (English) social murder, the serial killer represents a sort of psychological variant. In other words, the murder issues not from some external motive but rather from an internal perversion.

The move from the social to the psychological is one from England to America, as the murder stories consumed postprandially by readers (and later listeners and viewers) moved from social competition to psychological pathology. In the post-war peak of the American twentieth century, it was the serial killer who became the key figure in the cultural portrayal of murder.

If the American serial killer was preceded in our cultural imagination by the respectable, British, middle-class, “social murderer,” should we expect a new murderous ideal-type with the decline of American hegemony? As the narrator in Bret Easton Ellis’ 2023 novel The Shards remarks, the serial killer of the 1970s and 1980s was transformed into the mass killer of the 1990s and 2000s. The school shooter replaces the intelligent psychopath as a cultural figure of danger. It is telling that Ellis uses the backdrop of a serial killer at large effectively to create the feel of the 1980s in setting his novel in that decade. The portrayal of the serial killer today represents a certain nostalgic impulse to return to the good times of the American century, before its decline in the 1990s and after. Zac Efron’s portrayal of Ted Bundy in the 2019 Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile and the TV series dramatizing the life of Jeffrey Dahmer both draw on the setting of the America of recent memory to paint a picture of a charming sociopath in Bundy’s case or a violent and cruel man struggling with his sexuality in Dahmer’s.

The true meaning of the nostalgia around the serial killer comes through in the Netflix show Mindhunter. Mindhunter is created by David Fincher, who is one of the masters of the serial killer form, having directed the comic-book gruesome Se7en and the slow burn portrayal of the hunt for the 1970s Bay area killer in Zodiac. The basic premise of Mindhunter is that behavioral science in the 1970s allowed a historic shift: instead of just responding to the horrible crimes of the serial killer, analysts would be able to predict future murders through psychological profiling and data analysis. In the show, this scientific development offers Fincher a chance to use conversations between FBI agents and incarcerated serial killers to explore the motivations of the serial killers at large, while also looking back on a strange sort of “golden age” of famous mid-century American serial killers (such as Ed Kemper or Jerry Brudos).

Mindhunter is clearly a show about the “golden age” of post-war America, glimpsed through its darkest aspects. With the ending of the twentieth century and the unravelling of American hegemony since the 1980s, such a self-confidently and clearly American show could only be set in the past. It is here that a key difference between the serial killer and school shooter becomes clear: the research of the FBI in Mindhunter is able to categorize and explain the serial killer, which is impossible when faced with the blank, terrible, and inexplicable nihilism of the school shooter. Unlike the school shooter or the terrorist, the serial killer’s murders are only ever about themselves and their psychological damage. They never carry a wider political message or speak to a political cause. In other words, they are the reflection of a cohesive post-war, vaguely social democratic society. This is in stark contrast to the overwhelming, indiscriminate destruction of the terrorist or the school shooter, who will set off a bomb or plan an attack that destroys life indiscriminately. There is no meaning or recourse possible here, no motivational explanation that can in any way repair the destruction.

The serial killer, in this sense, offers psychological meaning, while the school shooter represents a far more disconcerting meaninglessness.

Ultimately, then, the serial killer’s monstrousness provides the same sort of comfort Orwell identified in the murderer, combined with nostalgia for the thriving America of the post-war era. There is no going back to this period of (relative) safety and meaning, even as it is glimpsed through those who threatened that safety. Instead we are faced with a more uncertain age. While it seems that American cultural ideas can retain their dominance even in a period of political decline and challenge to American economic pre-eminence, the nostalgia for the age of American dominance can only remain uneven, as some elements of that hegemony persist long after their use-by date.

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why, alongside those who long for the thriving America of the post-war period, there are also those who celebrate the contemporary collapse of meaning. Thus we see the Gen Z obsession with the Unabomber, or the edgelord sympathy for the Columbine shooters or incel murderers like Alek Minassian. In both cases, the deep alienation of that generation is tied to the appeal of a completely anti-civilizational detachment—a rejection of society rather than a pathological inability to exist within it. The more widespread these sentiments become, the more the collapse of the structure of meaning that made the serial killer such a compelling figure will have opened the door for the destructive nihilism of the inexplicable.

■

George Hoare is a writer based in London. He is a host of the Bungacast podcast and co-author of Taking Control: Sovereignty and Democracy After Brexit.