Who Invited Robert?

Robert’s Rules of Order were designed to make large organizations of members with disparate interests and customs functional. No surprise that they have been rejected by many left groups since the 1960s, who have been less interested in functionality than comradery.

In American politics, many people hate Robert’s Rules of Order. Robert’s Rules have been dragged as everything from “inefficient” to promoting “systemic racism,” and are even blamed for the dysfunction of the US Government. Nevertheless, there is something quintessentially American about Robert’s Rules of Order. They were created by an American army officer, in a uniquely American place, at a pivotal time in American history. Their meteoric rise in use and eventual fall from grace in leftist politics tells an illuminating story about American organizational life.

Robert’s Rules sprang from gold rush-era San Francisco. Even after the initial fever of 1849 had abated, San Francisco retained its reputation as a turbulent boomtown in which fortunes could be made and lost overnight. Henry Martyn Robert arrived in San Francisco in 1867 and was aghast at the raucous associational life he discovered there. Churches, fraternal organizations, businesses, and civic groups of all kinds were sprouting up chaotically, and inevitably had difficulty maintaining any coherent order. “San Francisco was made up of people from every state in the union,” Robert wrote, “and consequently members were being constantly ruled out of order, and there was no way to determine what was in order as the presiding officer followed the customs of the section from which he came.” The flood of immigrants to San Francisco from all corners of the world meant not only obstacles to a uniform culture of civil debate, but also a host of political issues on which to disagree. The Baptist church to which Robert belonged was nearly “rent asunder” by issues such as slavery, universal suffrage, and even a “heated debate as to whether the Corresponding or Recording Secretary should issue a letter of thanks ‘to the Ladies who managed the Strawberry Festival’,” as one of Robert’s fellow congregants recalls. Without any common cultural ground, the citizens of San Francisco found themselves adrift when attempting to make even minor decisions in modestly-sized assemblies.

Despite the general lack of homogenous cultural registers, San Franciscans did tend to share a faith in participatory democracy, a prioritization of efficiency, and a rejection of traditional hierarchies: three tenets which made a formalized set of organizational rules a precondition for effective association. As historian Don H. Doyle has argued, the creation and adoption of Robert’s Rules of Order fit hand-in-glove with the transformation of American life during the “golden age of fraternalism.” As markets became nationally integrated, transportation became faster and more easily accessible, and nationwide professional societies of all kinds rose to prominence, a standardized parliamentary authority became both desirable and necessary. “Corporate boards, professional associations, women’s clubs, and reform societies,” Doyle notes, “could no longer tolerate the inefficiency and conflict that diverse local and state traditions of parliamentary procedure allowed.” “Robert's Rules of Order did not simply respond to an obvious demand,” Doyle continues, “it anticipated, as early as the 1870s, the needs of a nationally integrated society. More important, Robert’s Rules in no small way amounted to an indispensable prerequisite—or at the very least a vital catalyst—to the organizational revolution that coincided with its rise.” The near-universal adoption of Robert’s Rules around this time paints a striking picture of American institutions. Organizations of all stripes were hungry for the national stage and no longer satisfied with regional colloquialisms; groups of people everywhere were joining together, eager to get things done, and jockeying for nationwide influence.

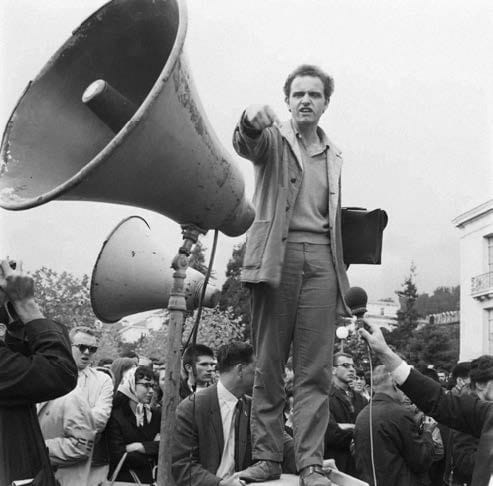

In a striking bit of mirror-image serendipity, Robert’s Rules found their most vocal critics just across the Bay, almost exactly 100 years later. The Berkeley Free Speech Movement (FSM) would experience similar growing pains to Robert’s Baptist church, albeit in reverse. The FSM, which prefigured many of the New Left student demonstrations that would follow, roundly rejected parliamentary procedure in favor of consensus decision-making. Although consensus decision-making had its origins elsewhere, the rejection of parliamentary authority in political circles is in no small part due to the Berkeley FSM. “Perhaps the earliest public advocate in the New Left of this ‘new’ style of decision making was Mario Savio, leader of the seminal Berkeley Free Speech Movement,” writes Scott Henson for the American Institute of Parliamentarians. “There’s no doubt,” Henson continues, “the popularization of consensus-driven decisions on the left first flowered beyond Quaker meeting rooms in America with the rise of the 60s rebellions.”

The FSM occupation of UC Berkeley’s Sproul Hall in December 1964 is a paradigmatic example of the consensus organizational principle in action. Over 6,000 students participated in the sit-in protest, where Joan Baez gave an early performance. Mario Savio stood on the building’s steps to give an impassioned speech against the faceless, machine-like bureaucracy of the university system. Over 1,000 students went inside to occupy the building, and historian Bret Eynon describes the atmosphere:

Once inside, the students took over four floors of the building, and settled in the halls and meeting rooms. Some studied, others watched Charlie Chaplin films. Some people organized a kind of alternative university with a mix of standard academic courses and such imaginative offerings as “The Nature of God and the Logarithmic Spiral.” Several different religious services were held, and a huge meal was prepared. Everywhere people talked about what would happen next, and what should be done.

Early the next morning, the students were swept out with the aid of police tear gas. It is perhaps telling that despite the all-night effort to build consensus about “what should be done,” the FSM was left without a coherent national platform. Nevertheless, the students built friendships and strengthened communal bonds within the bowels of a “faceless, machine-like bureaucracy.” Indeed, the FSM Steering Committee articulates this point precisely in their pamphlet “We Want a University”: “In our practical, fragmented society, too many of us have been alone. By being willing to stand up for others, and by knowing that others are willing to stand up for us, we have gained more than political power, we have gained personal strength.”

As the sit-in at Sproul Hall demonstrates, the mission of the student activists was not to build a national political platform—the kind of mission for which Robert’s Rules was designed. Robert’s Rules is a poor substitute for intimate conversation geared towards cultivating “personal strength.” This is a goal to which consensus-building is much better suited. Rather than effecting political change, the students, through their efforts to build consensus, were instead pantomiming a more caring, comforting university—one with groovy spirals, funny movies, folk music, and plenty of food. Although the university was less than receptive to their initial appeal, in the long run, the cry of FSM students for a more nurturing university has found its way deep into administrators’ hearts. Today, the steps of Sproul Hall bear a commemorative brass plaque ordaining them the “Mario Savio Steps.”

The FSM was not unique in this regard: Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was similarly uncomfortable with parliamentary procedure. Although SDS national conventions were nominally run under the aegis of Robert’s Rules, Kirkpatrick Sale, in his memoir, SDS, describes the impatience with formal organization among young SDS members at the Summer 1966 Clear Lake convention:

Contempt for steering committees, chairmen, parliamentary procedure, “structure,” “top-down organizing,” and any other hint at rigidity was evident from the start. So many people walked out of meetings to carry on their debates under the trees or on the raft anchored in the lake that new SDSer Mark Kleiman was encouraged to issue a call denouncing “parliamentarianism” and asking “people who are interested in finding other ways” to contact him at the National Office. (It was an echo of a notable incident at the previous National Council meeting when one delegate publicly burned his SDS membership card as a protest against the “undemocratic” way the council was being run.)

The lack of deference to parliamentary authority seems characteristic of SDS meetings generally. As Sale notes, “SDS conventions were always bizarre affairs, part reunion, part student-government meeting, part cruising strip, part smoke-filled room, part serious politics. In one sense,… conventions never really changed much for the organization, since individual chapters went their own ways and determined for themselves what SDS would be.” SDS president Tom Hayden would prefigure Twitter critiques of Robert’s Rules by standing up in the middle of meetings to browbeat the assembly with rhetorical questions like, “Suppose parliamentary democracy were a contrivance of nineteenth-century imperialism and merely a tool of enslavement?” Sale interprets Hayden as “attempt[ing] to enunciate a politics on the other side of the parliamentary forms handed down from another era, to see if there was a way of carrying on the business of society without all the trappings of the society of business. Hayden saw that SDS was caught in the bind of trying to create a new world with the tools of the old.” In this climate, as Sale remembers fondly, “Leaders were played down, and found to be often dispensable; meetings could be run without Robert’s Rules of Order and elaborate procedures, and decisions were arrived at, often, through consensus.”

Nevertheless, without any central organization or clear hierarchy, there was no common structure to hold SDS together during the disagreements that would follow over the Vietnam War, Communism, and militant tactics like those employed by the Weathermen. The SDS, already a loose conglomeration of localized factions, grew ever looser, and had for all practical purposes disbanded by 1974.

Why were the decision-making principles thought to be so vital to effective organization in the 1860s rejected by the student movements of the 1960s? The answer, Francesca Polletta argues, has to do with friendship:

Participatory democracy stopped working in the 1960s when its practitioners came up against the normative limits of friendship. Lacking organizational blueprints for creating functioning participatory democracies, activists in the early 1960s retained conventional structures like formal offices, majority votes, and Robert’s Rules of Order—but in practice ignored them. To make decisions and allocate resources, they relied instead on a participatory ethos combined with the natural goodwill, trust, and respect that friends have for each other. The groups that I studied did not begin as groups of friends. But the sense of finding allies in what seemed a wilderness of student apathy, combined with the long hours, the hard work, and, in some cases, the danger to which they were subjected as well as the excitement of launching a new movement, created strong bonds.

Robert’s Rules were designed to make organizations of people with disparate interests and manners functional, not to foster the feeling of friendship. Indeed, Robert took it for granted that members of an organization would not be friends, and designed his procedures to get things done regardless. The student groups of the 1960s, by contrast, were trying less to form effective representative political groups and more to find comradery and community. In short, community groups in the 1860s were trying to get organized; the students of the 1960s were isolated individuals trying to become a community.

Tom Hayden, former SDS president, articulates this point quite directly when he laments that “Robert’s Rules might suit a representative institution, but it doesn’t suit a fledgling social movement.” While Hayden may be correct, it is hard not to detect a tone of political defeatism in his condemnation of Robert. In Hayden’s conception, political organizations are not about representation, but about participation, open communication, and preserving friendships. In short, a good political organization is a friendly, supportive community. It makes sense why parliamentary authority would be eschewed in favor of consensus in these circumstances. It’s also worth noting that consensus decision-making is inherently more exclusionary than formal procedures for debate, as its aim is not to respect and reconcile disparate interests but to marginalize anyone who cannot participate in the “consensus.”

Consensus decision-making found political expression once again with Occupy Wall Street. Movement participants employed an elaborate system of hand gestures to generate something nominally called “consensus,” but which never resulted in a notable political resolution. This should not be surprising. Indeed, The Facilitator’s Fieldbook defines consensus decision-making as follows: “If any member of the group believes the existing status quo is better than the proposed alternative(s), the status quo will be the group’s decision.” Consensus is, by design, a method for maximizing the engagement of participants while maintaining the status quo. Nevertheless, in a social environment bereft of any established communal structures, consensus can help isolated individuals feel like they are participating in something communal. At this, Occupy—like FSM or SDS—succeeded quite well.

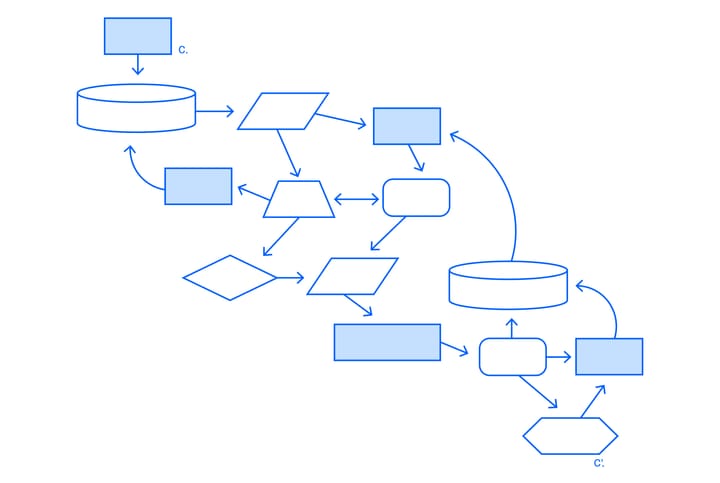

As Henry Martyn Robert well understood, decisive organizational action requires clear procedures for democratic deliberation and efficient decision-making. But “democracy” does not mean that everyone gets everything they want. When deliberating any issue with actual stakes, legitimate differences will inevitably arise and decisions must be made to move a group forward without requiring that everyone agree. In this mission, Robert has provided us with a valuable resource. Robert’s Rules are for people who want to do something. Consensus is for people who want to feel something. We should be clear-eyed about which we want more.

■

Taylor Hines teaches at Arizona State University.