Issue #3 Editorial Introduction: Mother’s Little Helpers

The editorial introduction for our third print issue, "Mothers." Out soon! Become a paid subscriber today to make sure you get a copy.

According to Google Ngram, there are two waves of prominent uses of the phrase “Mother’s Little Helper.” Predictably, one crests in 1970, the year that the Controlled Substances Act was passed. The years prior had seen a steady stream of articles in outlets like Good Housekeeping about suburban housewives struggling to wean themselves off of amphetamines or benzodiazepines. The song “Mother’s Little Helper” kicked off the Rolling Stones’ album Aftermath in 1966. Black market drugs were in the crosshairs of legislators, but so too were white market medications and the excesses of a pharmaceutical industry that had given us everything from thalidomide to LSD.

The second began to swell in 1987 and peaked in 2010. 1987 was the year the blockbuster antidepressant Prozac was released, and ads for SSRIs often depicted things like moms in business suits making deals on their cell phones while dropping the kids off at soccer practice. Moms didn’t just need help with the isolation of their domestic cells, they now needed help doing it all. The phrase also pops up in articles where the drugs aren’t targeted at women: in 2010, The New York Times ran an article titled “Modern Mother’s Little Helpers” about ADHD and OCD medications for kids.

Today, mothers have all the helpers of the post-war and neoliberal periods and more. Moms are microdosing mushrooms and LSD, they’re doing ketamine therapy, and they’re traveling to ayahuasca retreats.

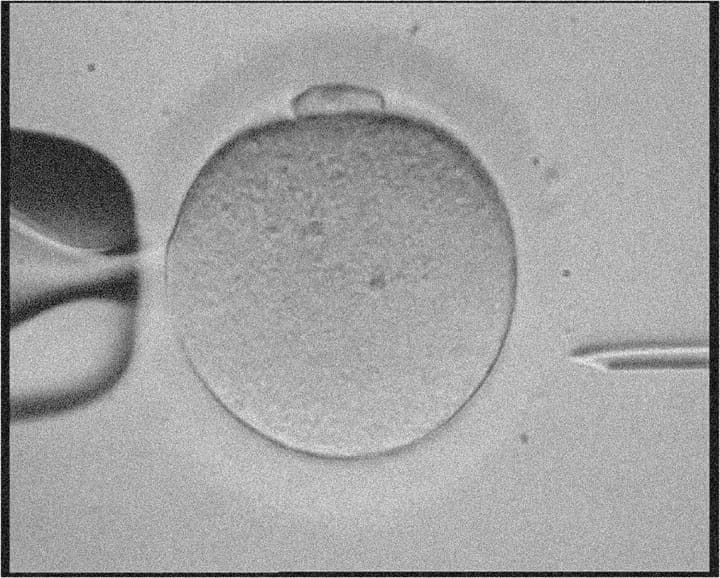

Soon the helpers might be in charge, the mothers left as vestigial appendages.

Why do we find such stories about the chemical enhancement of mothering simultaneously predictable and worrying? Amphetamines and benzodiazepines were marketed to men as much as women in the post-war period, and yet they’re remembered as the crutch of housewives. Today, you hear about “wine moms,” but why not “beer dads”?

Psychoanalytic theory has long been obsessed with the special state of what analyst Wilfred Bion called maternal reverie—where mother and infant are no longer one but only two in the physical sense, where needs are intuited and care is provided in such a way that can only be called psychotic from the outside. Given the maternal psychosis from which most of us emerge, it’s no surprise that the mixture of moms and drugs evokes strong feelings. Motherhood is a pristine ideal: it is supposed to be efflorescent, not propped up with intoxicants.

It is also the engulfing origin of consciousness—an everlasting threat to autonomy and maturity.

The reality, of course, is much more banal: kids are tough, and moms need all the help they can get.

Motherhood is perfect, motherhood is terrifying, motherhood is impossible. To corrupt it is demonic, to juice it is threatening, and to prop it up is all but expected.

In the modern period, motherhood is also an attempt to escape this contradictory matrix. According to the English translator of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House, modernity began at the precise moment on December 21, 1879 when an audience first heard Nora slam the door shut at the end of the play, leaving her husband and children, seemingly for good. “Their heroine had gone from her lilting entrance, a slender, vulnerable creature of macaroons and Christmas toys, to her final departure, a remorselessly independent figure wreathed in a funereal shawl.” Bernard Shaw said that “Nora’s revolt is the end of a chapter in human history.” “God is dead” looks quite silly compared to “Mom left.”

Again, the reality is more mundane: when mom leaves home, it’s typically not to go out in search of authenticity and autonomy but because she has to work. What Copenhagen theater-goers came to fear that night in the form of an independent woman was, partially, looming economic compulsion.

Today men have a higher labor force participation rate, but the gap between men and women has been slowly closing for decades, and as of 2022, women outnumber men in the US college-educated workforce. It makes sense that women are waiting longer and longer to have kids, if they have them at all.

Still, 86% of American women between 40-44 are mothers, up from 80% in 2006. Add these trends up, and you won’t be surprised to learn that more mothers are working than ever before.

The feared “opt-out revolution,” where professional women ditch their jobs for motherhood, never came to be.

The general fertility rate nonetheless continues to decline, meaning amongst other things smaller and smaller families.

The US also has an alarmingly high maternal and infant mortality rate.

And we have the world’s highest rate of children living in single-parent households (80% of single custodial parents are mothers). Having a child is a particularly risky proposition in America; it makes sense that parents are doing it less.

At the same time, 87% of them also find parenting to be either one of the most or the most important aspects to who they are as a person.

Stretched thin between work, parenting, and other care commitments, focused on fewer children but in increasingly precarious circumstances, mothers turn to their little helpers for very straightforward reasons. Rather than concern ourselves with what our moms do to get by, however, perhaps we should think about the big helpers—the broad structural changes needed in American society that would strengthen families by providing material security, and which might obviate the need for daily dosing. You might not think you’d benefit personally from universal healthcare and a jobs guarantee, but before you turn against them, consider the mothers.

This issue is dedicated to Jane Liu, who passed away on May 29, 2024.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong is the author of Quick Fixes: Drugs in America from Prohibition to the 21st Century Binge (Verso, 2023) and the producer/host of Organize the Unorganized: The Rise of the CIO. You can find his other work at benfong.com.