How the Online Right Fell Apart

Behind the scenes, the online Right is just as divided as the Left—and it’s adopted many of its pathologies too. Are we facing a fascist coup, or just a collapse into political confusion?

Before “weird” became the summer’s hottest and most contentious political insult, JD Vance cheerfully admitted to being “plugged into a lot of weird, right-wing subcultures.” Thanks to his candidacy, those subcultures are now being raked over by outlets like Politico and the New Republic. There’s some prim laughter at figures like Rod Dreher, who attributes most political events to the action of literal demons, or Curtis Yarvin, who wants to make the President of the United States into an absolute monarch. But behind these figures, the liberal press are starting to trace the outlines of something ugly. As liberalism stagnates, and with the Left absent from the stage of history, all the intellectual energy is now on the Right. The campus conservatives, the doughy GOP staffers, the army of worker-ants that keep right-wing politics running—they’re all marinating in an entirely new ideological sauce. The new Right, the dissident Right, the postliberal Right: extremely online and extremely hostile to the ordinary liberal principles of representation, individualism, and pluralism. They’re not pretending to read Locke anymore; they’re pretending to read Schmitt. Now they want to test out their ideas on the world.

None of this is untrue, exactly. There’s a growing infrastructure laundering fringe anti-democratic ideas and piping them into the heart of the Republican Party. But this is where most accounts of the new intellectual Right leave off. The clue to a fuller account is in the name: the new, dissident, postliberal Right are only united by what they claim to be opposing and superseding. This doesn’t get noticed much outside the online Right itself; everyone seems to think their own political faction is hopelessly divided, while their enemies are creepily unanimous. But when the liberal world order inevitably collapses and a bold new ideology rises from the ashes, what will that actually look like? Depends who you ask.

There’s a faction in the online Right that wants to build a Nordic-style social democracy, with strong labor unions, state control of industry, and a robust welfare state. (As Succession put it, “Medicare for All, abortions for none.”) So far, their plan to get there mostly seems to consist of writing long essays on Foucault. The monarchists, meanwhile, want a stratified, techno-feudal society of cyber-aristocrats and forelock-tugging digi-serfs. Some prefer Donald Trump to be their emperor, but by no means all. Plenty would be perfectly happy with Kamala Harris, as long as she uses the full power of the state to mercilessly crush all opposition. Yarvin, their intellectual godfather, is still formally endorsing Biden, despite his having dropped out. There’s a surprisingly influential faction of the American Right that wants to build a new political order based on Pindar’s Odes—a collection of lyric poems honoring the great athletes of the fifth century BC—and also eating raw eggs. A persistent current wants to turn the state into a minor facet of the Catholic Church. It’s true that less than a quarter of the country is actually Catholic, but maybe enough immigration from Latin America could yet transform the USA into the Empire of Our Lady of Guadalupe. There are even currents on the online Right who believe that the Caribbean was originally settled by white-skinned men from the North Pole, or possibly outer space. Others are outright neo-Nazis. That last group seems plain next to their neighbors. Unimaginative.

Supposedly, the principle keeping all these vastly disparate factions aligned is called NETTR, or “No Enemies to the Right.” The dictum is usually attributed to Charles Haywood, a former shampoo magnate who sold his business to spend more time blogging about the inevitable collapse of the liberal world order. It says that the only important goal is building a coalition to achieve “the total, permanent elimination of all Left power.” Any disagreements within the Right can wait. This means that if you’re mostly interested in, say, putting the Christ back in Christmas, but you find yourself in the company of people who wave swastikas and talk about the nefarious designs of the Jew, you should not say anything about it. There are no enemies to your right. Meanwhile, the swastika people are free to criticize you as much as they like; you, after all, are to their left.

According to its advocates, NETTR is just an imitation: the entire progressive wing of politics, from liberal centrists to Maoist-Third Worldists, has secretly been governed by a policy of “No Enemies To The Left” since the Kerensky government, or possibly the French Revolution. This might be news to anyone who’s spent any time in the radical Left. (Like amoebae, left-wing groups reproduce by splitting. Like amoebae, they’re also mostly asexual.) But again, everyone believes their enemies are much more united than their allies. In this context, NETTR is a bold experiment in trying to run a movement in imitation of your fantasy of your enemies.

Unsurprisingly, it hasn’t worked.

It doesn’t help that the divisions within the online Right don’t easily map on to any clear left-right axis. One major split emerged in 2022, when Curtis Yarvin, whom we've already met, tried to dissuade the Right from focusing on culture-war issues, abortion, or critical race theory in schools. These, he wrote, were issues for “hobbits,” dumb red-state bumpkins locked in a losing struggle against liberal metropolitan “elves.” As the internet's foremost monarchist, Yarvin has a generally low opinion of the broad mass of the people: he’s not impressed by the small victories of the hobbits in the War on Woke; his preferred path is a cultural palace coup by “dark elves”—that is, urban intellectual elites who are secretly “on the hobbits’ side.” In other words, instead of trying to ban abortion, the unwashed masses should just sit back and let Yarvin and his fellow far-right Gramscians do the important political work of rambling to cigarette-smoking models at Manhattan parties. This stance has made Yarvin an enemy of the Right's more populist currents, but it’s hard to say exactly who gets the benefits of NETTR. Is it more right-wing to have disdain for the masses? Is it more right-wing to hate the degenerate elites? Who is to the right of whom?

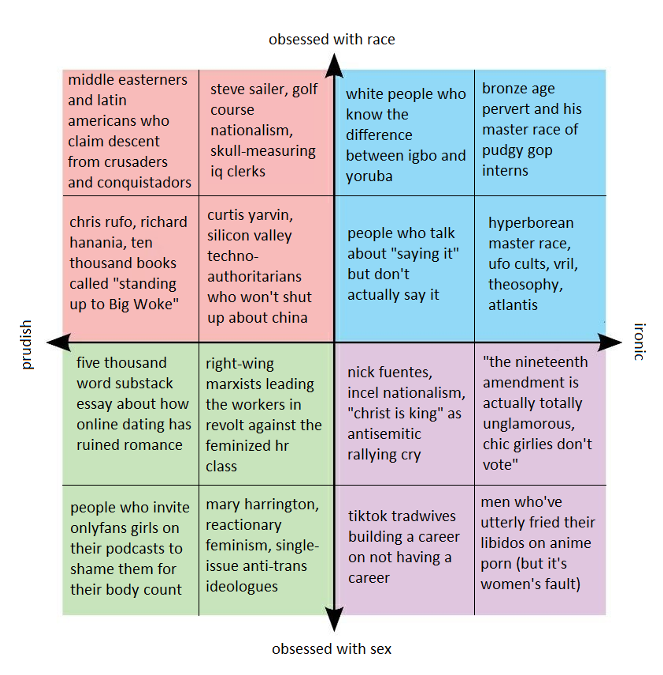

To understand how the online Right splintered, you need other axes. Playfulness against puritanism, elitism against egalitarianism, the culture war against the cosmic. The deepest split within the Right, though, is between “Christians” and “Nietzscheans.” Inverted commas, since the Christians don’t necessarily believe in God, and the Nietzscheans are not guaranteed to have read a single word of Nietzsche. What the sides represent is a cleavage that might be weirdly familiar to anyone who trudged through the last decade of online Leftism. What the Nietzscheans have taken from Nietzsche is the idea that people are not equal, that we come in different kinds, and a different kind of life is owed to us depending on those essential qualities. For the Christians, meanwhile, “there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” The same squabble between identity and universalism, again, on a new terrain.

Sohrab Ahmari is a Catholic, a former op-ed editor for the New York Post, and one of the founders of Compact, an online magazine pitched at the social-democratic wing of the new Right. In 2019, he was writing broadsides against all forms of liberal pluralism, encouraging religious conservatives “to fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” And the public square has been re-ordered, but maybe not in the direction he wanted. In May of this year, Ahmari railed against “America’s dime-store Nietzscheans” in the New Statesman, a British center-Left magazine. He noted that the intellectual currents of the Right were increasingly dominated by disaffected leftists, who had, in their rightward drift, skipped “normie conservatism” for the “triumph of the eugenic over the degenerate, the IQ-endowed over the low IQ, Anglos over ‘negroids’ and ‘beige people.’”

The Nietzschean faction views humanity as fundamentally split between the strong and the weak. Precise definitions vary—golf-course nationalists like Steve Sailer, who helped popularize “human biodiversity” on the Right, are mostly interested in poring over tables of cranial capacity by race, while the faction around Bronze Age Pervert disdains the bean-counting of “IQ clerks” for a more vital, chariot-riding, pyramid-of-skulls-building aristocracy of the spirit. It makes sense that a religious conservative like Ahmari, for whom all life is equally sacred, would find all this stuff unpalatable. Still, his article was taken to be a major violation of NETTR. In the firestorm that followed, a host of online right figures, including Curtis Yarvin, announced that they would refuse to work with Compact again.

But this doesn’t mean that the Christians are necessarily the more liberal faction. One of the major organs of the Nietzschean faction is Man’s World, a glossy online magazine edited by someone who calls himself Raw Egg Nationalist. Its first print issue featured 200 pages of essays on vitalism, esoteric nutritionism, and the Greek epics. It also included a photo of two women erotically mud-wrestling. One of them is a model, bassoonist and minor right-wing it-girl called Pariah the Doll, who is also a trans woman. This caused an instant explosion of fury from the “hobbits.” Suddenly, she became a litmus test. For the Nietzscheans, being trans is, on an individual level, not a big deal. There’s a Faustian spirit there. Man overcoming himself, becoming something new. But the universalism in the right-Christians’ moral universe is made almost entirely out of all-encompassing sexual neurosis. “If you are part of the Dissident Right, at your core, you believe in objective natural truth and the most simple test of that believe is the Trans Question.” Those who refused to turn on Pariah, including Bronze Age Pervert and Anna Khachiyan of the Red Scare podcast, were anathematized. For those who had once been part of the Left, it must have all felt very familiar. Whether it calls itself the Right or the Left, the real content of all online politics is the internet itself, and the arc of online politics always bends towards a bunch of strangers who spend their entire lives on the computer demanding that you publicly denounce your friends.

But what might be more significant than these squabbles is what the online Right hasn’t split over. Take, for instance, economics. Until last year, the reigning orthodoxy on the Right was an economic nationalism broadly associated with Steve Bannon: tariffs, industrial policy, redistribution, the common good. But when Bronze Age Pervert wrote an essay in Man’s World against the “‘economic populism’ that results in crushing taxation, regulations in the name of social justice that destroy all enterprise, and ultimately really the enslavement of the good, intelligent, and talented part of the population in the service of providing goods to the dumb, dusky stupid many,” this somehow failed to provoke a civil war within the online Right. Instead, a good chunk of the right-wing social democrats simply started pretending they’d been free-market advocates all along. Consistency is not a virtue here. Yarvin, for instance, is usually a dyed-in-the-wool free-marketeer of the Austrian school—but at the same time, his neo-feudal utopia involves “selectively reinstating preindustrial methods and structures of production” on the Ciceronian principle of Salus populi suprema lex esto, or that the good of the people should be the supreme law. This would require massive state intervention in the economy on a level that would make Stalin sweat. But while Yarvin’s enemies on the Right might get very upset over whether you should hate rich people or poor people, neither the new economic populists nor the radical marketeers bother to pick him up on this. They know not to take anything actually political too seriously. They know it isn’t really real.

Spend enough time watching the online Right, and it’s hard not to conclude that their politics are all for show. They like to claim that their breed of reaction is based on the rediscovery of timeless, eternal truths, whether biological or divine, but mostly it just looks like pure oppositionalism. The return of scientific racism is just a distorted mirror-image of the racial frenzy that consumed the Left in the Long 2010s. Four years ago, the line was that you could either dedicate your life to the work of constantly engaging with whatever drivel passed itself off as antiracism, or else you were racist. The new Right completely agrees. Meanwhile, the erotic obsession with virile masculinity is just an echo of girlboss feminism. Men are so powerful and important that they need special protections in the workplace. Lately, they’ve been arguing about whether it’s a good idea to form online mobs and get ordinary people who say things they don’t like fired from their jobs. The emerging consensus: yes, it is a good idea. They’ve managed to reproduce every single pathology that made the Left unbearable, but without the emancipatory drive that makes the Left worth engaging with all the same.

Sometimes, people trot out the idea that left and right are obsolete terms; politics has moved on, there are new formations now, new alliances, new axes running through the world. And it’s true that all of these things exist, but all of them are meaningless. I think a politics is meaningful only insofar as it’s clearly legible on the boring old left-right axis. Outside that, all you get is stuff like the dissident Right. If ordinary politics is slowly becoming weightless, untethered, increasingly incapable of representing itself coherently or representing any broader sector of society, the new online politics abandon any attempt at political substance for an infinity of shifting poses. Look at me, look at how dangerous and reactionary I am. In all their conflicts, there’s no actual vision of society at stake, just the clash of different stances: the pious, the impish, the wholesome, the perverse. This stuff poses a serious danger, but it isn’t the danger of a coherent anti-democratic ideology seizing state power. Something much more insidious. Once everything becomes a game of posture and affect, will it ever be possible to articulate a coherent politics again?

■

Sam Kriss is a writer and dilettante in London.