The Paranoid Style of Motherhood

Child abuse conspiracy theories are rife at present, but they predate QAnon, and they even go much further back than the conspiracizing that gave rise to QAnon.

The Great Flower Panic of 2021 began when an Ohio man gave his girlfriend an excessive amount of roses while proposing to her. His new fiancée decided to share her wealth, so she went with her sister and daughter to a Walmart parking lot and started leaving flowers on people’s cars. When WBNS-TV ran a story about this good-hearted gesture, the daughter described what they expected: “People are going to come out and think it’s awesome.”

But “that didn’t happen,” she added. Instead the roses were spotted by shoppers who had heard the urban legend that human traffickers deploy such items to distract their victims before kidnapping them. Soon the sheriff’s office was posting a warning on Facebook about “what appear to be” two “males” who were “looking into vehicles and placing a single red rose under the windshield wipers of those vehicles.” The warning added that “there have been several Facebook posts of similar instances that have happened in Ohio regarding Human Trafficking related techniques.” Mothers beware!

Once it became clear what actually had happened, the story went national. Several commentators blamed the overheated reaction on QAnon, a subculture whose members believe that Washington and Hollywood are controlled by Satanic pedophiles who try to obtain eternal youth by ingesting kids’ blood. The reporter Ben Collins, for example—at that point covering the disinformation beat for NBC—tweeted that this was a “QAnon moral panic.”

Such reactions got the chain of influence exactly backwards. QAnon didn’t pave the way for stories like the Ohio Walmart panic; stories like the Ohio Walmart panic had paved the way for QAnon. Dubious rumors of kidnapping-and-trafficking plots had been going viral on social media years before QAnon existed, sometimes with a boost from local news reports.

Here are a few examples:

- In 2014, some Oregon TV reporters somehow managed to wring an entire news report out of a car slowing down behind a bicycle. The girl on the bike “locked eyes” with the driver, decided he wanted to kidnap her, and then rode up her driveway to get away. This triggered her home’s motion-activated cameras, giving the broadcasters some not-quite-dramatic footage of a car stopping at the end of her driveway for a moment and then moving on. After the report aired—and was posted on the Fox website under the headline “Attempted kidnapping caught on tape”—the police learned that the driver had simply been searching for a shop.

- In 2015, a tall tale spread through email and Facebook claiming that a sex-trafficking ring had targeted a girl while her mother shopped at a Target store in Tampa, Florida. When Kim LaCapria of snopes.com debunked the rumor, she noted that similar stories had circulated that same year about child- and woman-snatching plots everywhere from Texas to North Carolina to Malaysia, none of them substantiated.

- Going back to at least 2015, a copypasta text has periodically gone viral on Facebook, and on at least one occasion graduated to some low-level news sites. It warns mothers that if they post a picture of their daughter on her first day of school, the photo might soon be texted to potential buyers around the world with the caption “American Female. Age 5 Brown Hair. Black Eyes. $5,000.” By the afternoon, “your precious baby girl was sold to a 43 years old pedophile before you even stepped foot off campus this morning, and now she’s on her way to South Africa with a bag over her head, confused, terrified and crying.”

All this has continued in the age of Q, running parallel to the more outré allegations percolating in the QAnon forums.

The deepest roots of QAnon go back far further than Facebook. Some of the oldest conspiracy fears involve threats to children—unsurprisingly, since parents are often anxious about their children’s well-being. For centuries, secret alien forces have purportedly been on the prowl for young victims, who they allegedly intend to rape, eat, sacrifice, strip for organs, drain of their youthful vitality, or otherwise consume.

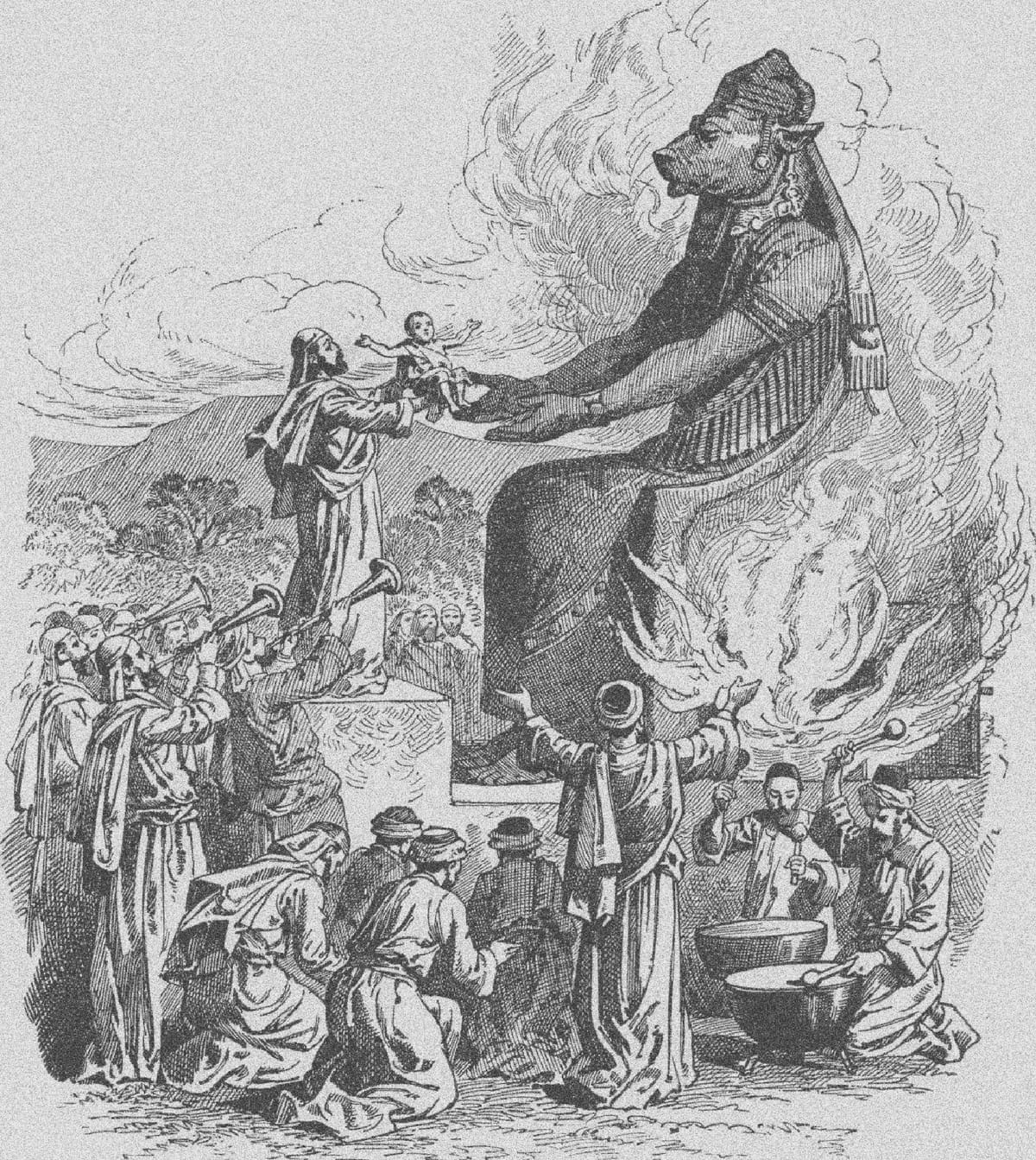

“The Old Testament associates the ritual burning of children with the cult of the Canaanite fire god Moloch,” the Newcastle historian Luc Racaut noted in 2002. “The Greeks and Romans were thought to sacrifice children to Kronos or Saturn, a deity which was often depicted as eating his own children.... In both cases, the ritual killing of infants was attributed to a pagan cult, that of Moloch among the Canaanite and to the cult of Saturn among the Romans. The versatility of the accusation of infanticide, associated with a hostile religious cult, points to its universal appeal as a mark of infamy.” The Romans accused both Jews and early Christians of killing and devouring children, and medieval Christians continued to lob the accusation at Jews for centuries afterward. Catholics also accused first heretics and then Protestants of the same crime.

The fourth-century bishop Epiphanius of Salamis wrote that the Gnostics

extract the foetus at the stage which is appropriate for their enterprise, take this aborted infant, and cut it up in a trough with a pestle. And they mix honey, pepper, and certain other perfumes and spices with it to keep from getting sick, and then all the revellers in this herd of swine and dogs assemble, and each eats a piece of the child with his fingers.

In that story, the cannibals consume their own offspring. In the more famous forms of the blood libel, the conspirators steal kids from outside their community. One enduring antisemitic legend claims that Jews use the blood of gentile children to make matzah. A separate set of conspiracy tales have swirled around the Roma, who for centuries have faced rumors that they abduct children to raise them as their own—or worse. In Bologna in 1990, a story spread that Gypsies in black ambulances were stealing children to supply the market for human organs; soon mobs were attacking Roma camps.

Around the same time, rumors swept several Central American countries that buyers from the US, Europe, or Israel were acquiring babies from impoverished mothers, supposedly to adopt them but actually to dismember them for valuable body parts. And across the 1980s and early ’90s, an important precursor to QAnon emerged in the United States, when the mass media embraced ideas that had previously been confined to certain conservative Christian subcultures, in which a covert network of Satanic cults was ritually abusing and even sacrificing American boys and girls.

Modern discussions of QAnon often suggest that it is an unprecedentedly popular phenomenon fueled by social media. But the Satanic Panic was far more mainstream than QAnon, and it accomplished this with no help from Facebook or Instagram. Its claims were aired uncritically on programs like 20/20, a respected TV news program, and the people who took those claims seriously included cops, prosecutors, and juries. Several men and women received long prison sentences for abuses that never occurred.

While mainstream institutions embraced the Satanic Panic, it contained a fringe too—a current convinced not just that we were surrounded by demonic cults but that the cultists had infiltrated powerful institutions. This folklore persisted after the wider panic receded, producing such paranoid books as Trance Formation of America (1995) and Thanks for the Memories...The Truth Has Set Me Free! The Memoirs of Bob Hope’s and Henry Kissinger’s Mind-Controlled Slave (1999). The allegations in those texts fed directly into the “Pizzagate” and “frazzledrip” tales of the late 2010s, in which Hillary Clinton and others took the roles formerly filled by Hope and Kissinger. Ultimately, they fed into QAnon. And while sloppily phrased poll questions have sometimes led people to exaggerate the popularity of these stories, they are clearly better-known now than they were in the interval between the early ’90s and the late ’10s.

Why did the public become more receptive to such rumors? Partly because there were two major news stories, one centered around the financier Jeffrey Epstein and the other around the TV star Jimmy Savile, in which powerful people really did prey on minors sexually while other powerful people looked the other way. The revelation of real scandals always makes it easier to imagine larger, more elaborate forms of misbehavior. (When Carl Beech fabricated tales of a vast pedophile ring in the highest levels of the British government, one reason the police took his claims so seriously—with one investigator declaring gullibly that the story was “credible and true”—was the Savile precedent.)

But there was another reason the public was more receptive: because law enforcement agencies and sympathetic politicians had taken to exaggerating both how common and how organized sex trafficking is. As Elizabeth Nolan Brown reported in Reason in 2015:

Globally, some 600,000 to 800,000 people are trafficked across international borders each year, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimates. But the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2006 described this figure as “questionable” due to “methodological weaknesses, gaps in data, and numerical discrepancies,” including the rather astonishing fact that “the U.S. government’s estimate was developed by one person who did not document all his work.” And even if he had, there would still be good reasons to doubt the quality of the data, which were compiled from a range of nonprofits, governments, and international organizations, all of which use different definitions of “trafficking”....

Rep. Joyce Beatty (D–Ohio) declared in [May 2015] that “in the U.S., some 300,000 children are at risk each year for commercial sexual exploitation.” Rep. Ann Wagner (R–Mo.) made a similar statement that month at a congressional hearing, claiming the statistic came from the Department of Justice (DOJ). The New York Times has also attributed this number to the DOJ, while Fox News raised the number to 400,000 and sourced it to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). But not only are these not DOJ or HHS figures, they’re based on 1990s data published in a non-peer-reviewed paper that the primary researcher, Richard Estes, no longer endorses. The authors of that study came up with their number by speculating that certain situations—i.e., living in public housing, being a runaway, having foreign parents—place minors at risk of potential exploitation by sex traffickers. They then simply counted up the number of kids in those situations. To make a bad measure worse, anyone who fell into more than one category was counted multiple times.

Coerced labor is a serious social problem, but most of it does not involve sex; and the sort that does involve sex is far more likely to involve criminals victimizing people in their immediate social networks than to be conducted by vast conspiracies. (The Anti-Trafficking Review reports that “only about five per cent of prosecuted human trafficking cases in 2020 [in the U.S.] involved exploitation directed by gangs or organized crime groups. Instead, most cases involve individual traffickers acting as ‘pimps’, operating without direction from or connection to a larger criminal network.”)

It certainly isn’t likely to involve the sorts of parking-lot kidnappings that Facebook moms love, let alone the bizarre claims that bubble out of the QAnon subculture. Yet such stories have staying power, and not just among moms: plenty of dads and uncles also believe in Q. A recent paper in Scientific Reports, drawing on survey data from 2021, did not find any significant correlation between gender and QAnon belief. This didn’t surprise Joe Uscinski, a political scientist at the University of Miami and a coauthor of the study. “Sex is rarely a good predictor of conspiracy theory beliefs,” he tells me.

If there is a particularly maternal, as opposed to parental, character to some of these stories, it isn’t because mothers are more likely to believe in plots against their children. It’s because these tales sometimes spread through particularly feminine networks and settings, from the mommy groups that hosted so many pre-Q Facebook rumors to the wellness-focused Instagram accounts that traffic in what Marc-André Argentino has called “Pastel QAnon.” There is a paranoid style of motherhood, and there is a maternal style of paranoia.

And that style is ancient. A mother’s fears are nearly as old as a mother’s love.

■

Jesse Walker is author of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory.