We love our moms, and we love our movies. It’s Damage’s top ten movie moms. (Plus one because Almodóvar loves his moms, and plus another because RIP Shelley Duvall.)

Boyhood’s Olivia Evans (Patricia Arquette)

In Boyhood's first scene between titular boy Mason, then six years old, and his mother Olivia, she is driving him home after a disciplinary meeting with his teacher. Here is a working single mother, who probably drove there straight from work, probably then straight home to feed two kids, and yet the after-school meeting over Mason's mischief is met with patience and curiosity.

As the years pass—Boyhood was filmed over the course of twelve years—Olivia juggles work, grad school, and childcare. She frets over bills at the kitchen table in multiple homes and instructs her daughter to sell tchotchkes over eBay “because we’re house-poor.” Mason's distant but also loving dad, on the other hand, enjoys the time and space to grow as a person, father, and actuary. He takes the kids bowling, camping, and running around outside, while Olivia’s mostly portrayed working in some capacity.

At one point, Olivia encounters someone she’d crossed paths with years earlier. Formerly a day laborer to whom she’d paid a compliment and suggested night school, now having blossomed into restaurant manager, the man thanks her profusely for changing his life. It’s an unsubtle reminder to her kids, and the audience, just how good she is.

Olivia is not without flaws, however. She subjects herself and her kids to a “parade of drunken assholes,” including an alcoholic husband whose abuse drives her to rescue her kids from their erstwhile step-family. In their final scene together, with Mason now leaving for college, Olivia's implausible grace toward her son finally cracks. "I knew this day was coming. I just... I didn't know you were going to be so fucking happy to be leaving."

Boyhood filmmaker Richard Linklater observes Olivia through the rose-colored glasses of a son who loves his mother, but with the understanding of a man who’s navigated parenthood himself. In short, it’s a movie for men who love their mothers.

Rosemary’s Baby’s Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow)

One theory of myth argues that its power lies in its capacity to turn the terrifying forces of nature and the unknown into names—if not to conquer nature’s sublime power, at least to make it identifiable. The horror genre works in the opposite direction. The anxieties, paranoid projections, and violence of social life metamorphose into forces of supernatural evil. If myth domesticates untrammeled nature outside and within the individual, then horror estranges the repressions required by civilization, casting a light on the hidden traumas that make it possible.

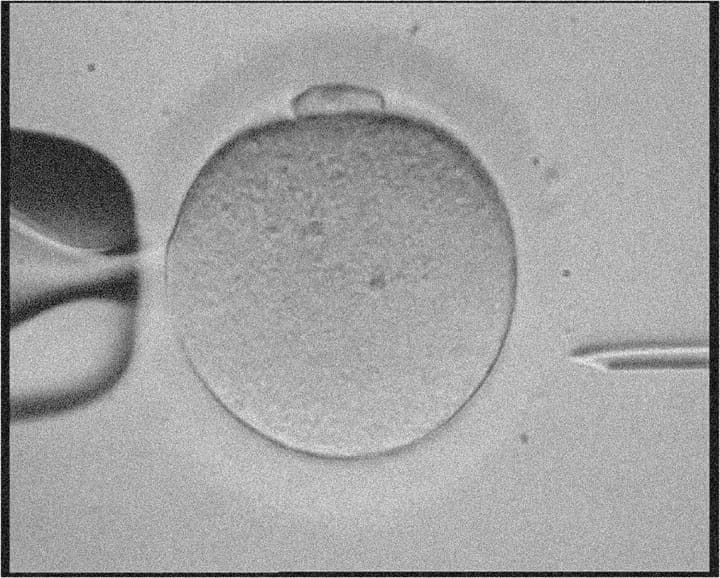

Pregnancy is a powerful theme for a horror story because it embodies both sides of this complex: the back and forth between society and nature, the confusing pain of our biological inheritance as it spawns the weave of generations and perpetuates the doomed, fallen status of collective human endeavor. In Rosemary’s Baby, the anxieties of pregnancy, usually ironed out through images of the majesty of motherhood and the magic of birth, become monstrosities. In this world, meddlesome in-laws become members of a witch’s coven with terrible designs on the child’s future. The father is no longer a loving husband but a self-absorbed and untrustworthy yuppie, critical of Rosemary’s fears and abusive when she tests her autonomy. Instead of sex between a loving couple, Rosemary is drugged and raped, presumably by Satan, on the night the child is conceived. Then there are the constant worries about the mother’s health, the feelings of isolation. There are difficult pregnancies, but Rosemary’s is torture. She is force-fed disgusting concoctions to aid her pregnancy, but her lively glow becomes a sickly pallor. She becomes thin, frail, and gaunt, beset by unbearable convulsions. Her complaints fall on deaf ears—the doctor is also plying his trade in the name of Lucifer.

But all these horrors are fundamentally in service of a much more basic one at the heart of the film: that the inevitable split between mother and child, necessary both for life and social reproduction, is a force of evil. The baby that has spent nine months growing inside the mother will become, at the moment of birth, not just an individual but a new member of society. From that moment on, Rosemary’s baby is never fully hers.

In its famous final scene, the film depicts the terror of reproducing all sociality. The world will depend on the mother for her body and the care she provides the infant, but it will eventually demand her most prized possession for the service of its own designs. And its bonds are not the bonds of love, but of Satan.

The Waterboy’s Helen Boucher (Kathy Bates)

In this classic coming of age tale, a thirty-one year old boy lives a clandestine life that is both an act of defiance against his overbearing mother and also made possible by her. For he is only able to secretly participate in a violent and devilish underworld by unleashing a lifetime of repressed aggression within it. He is not made for it (and can only participate in its rituals with a steady outpouring of terrified whimpering), but he is its master—an off worlder destined to rule.

At first, his mother remains ignorant of his victories, and of their spoils. He has slapped hands. He has seen breasts. He has learned of the medulla oblongata. But she invented electricity, and when she discovers the truth, the lights go out.

So the boy stops. He cedes his reign for her love. And it is his demonstration of ultimate fidelity that enables her to finally embrace his violence and mastery. The film ends with the mother knocking the boy's father unconscious and ordering the boy to lose his virginity through the consummation of his marriage.

Psycho’s Norma Bates (Norman Bates)

When Norman Bates, a shy, obsequious, and odd man who runs an isolated motel on a semi-abandoned stretch of highway, first mentions his mother in Hitchcock’s Psycho, it is to tell his sole patron, a secretary on the lam from Phoenix with $40,000 she stole from her boss, that she “isn’t quite herself today.” It is only at the end of the film, when we discover that Norman has been wearing his mother’s clothes, speaking in her voice, and replacing his personality with her own, that we understand the dark truth hidden in that statement.

Hitchcock liked to make the mind’s power of substitution central to the drama of his films. If people and things previously cathected with dense emotional energy are, for whatever reason, no longer available, the mind finds replacements. Identities become more liquid and fragile. You no longer have the watchful eye of the parents, but a series of watchful eyes: bosses, policemen, private investigators. A lover is replaced by her sister. Sources of intense anxiety are conjured up as they are in dreams. But the process never goes smoothly. Substitution tends to reduce whole objects to parts.

At the end of the film, a psychiatrist explains that Norman, after murdering his mother and her lover in a jealous, Oedipal rage, coped with her loss by living as both sides of the couple. But if there were once loving, caring parts of his mother, now they are gone. We are left with a voice reduced to pure aggression: a castrating, murderous, obscene superego living high above the motel, a seedy place where seduction occurs.

Everyone, to some extent, becomes their parents. This is partly a natural fact, but it is also horrifying. Norman stands in for the child who never managed to flee the coop, wasting his life living atop a motel full of taxidermied birds. At one point, he tells Marion that he was “born in a trap,” poisoned by his mother’s nest. Norman Bates failed the child’s basic test of autonomy: the burden to break free.

The Birds’s Lydia Brenner (Jessica Tandy)

The bird motif returns in another one of Hitchcock’s mother and son films, The Birds. A handsome lawyer named Mitch recognizes Melanie, a San Francisco socialite, in a pet store while he is there to purchase a pair of “lovebirds” for his sister Cathy’s 11th birthday. After a brief flirtation, he leaves without buying them. Melanie purchases the birds and hatches a plan to secretly leave them at the seaside home of his sister and overbearing, jealous mother Lydia. Mitch spots Melanie making the drop and drives to intercept her at the wharf before she has time to leave. That is when the first bird attack occurs. Melanie’s head is left bleeding, and Mitch tends to her in a nearby diner.

The bird attacks have been subject to a panoply of interpretations, and they ultimately play a contradictory role. On the one hand, the birds function as a projection of Lydia’s competitive hatred for the new woman. Early on, Melanie meets Mitch’s former lover Annie, who explains that Lydia’s poisonous jealousy ruined their relationship. Later, Annie is killed by the birds. The mother’s hatred for the rival of her son’s love is sublime, omnipotent, and violent. Eventually, the birds’ aggression becomes indiscriminate and overwhelms the entire town.

On the other hand, the attacks prevent Melanie from leaving and ultimately drive the couple together. One of the puzzles of the film is to figure out why the birds strike when they do. It appears random. Often they simply gather and wait. But in almost every case, the onslaught solidifies the bond between the lovers. After the birds have left the town in devastation, the new family can finally take shape, and they flee Bodega Bay together. Before they jump in the car, however, Cathy remembers to grab her lovebirds, which appear to be exempt from the murderous aggression that has gripped the rest of ornithological life.

In the end, they seem mostly to embody the fundamental ambivalence that makes all relationships possible. Even Lydia has to submit herself to this demand, that hate must ultimately be mingled with love.

Beau is Afraid’s Mona Wassermann (Patti LuPone)

In the first part of Kafka’s “The Judgment,” the protagonist, a young man named Georg, voices his anxieties about disclosing his recent engagement to a friend in St. Petersburg. The picture is of a self-possessed young man on the precipice of a new stage of life, confident if a bit obsessive. In the second part, his confidence is wrecked in a dialogue with his father, who embodies incomprehensible, unconquerable power, a figure of brutal omniscience. He makes a performance of his frailty but mocks his son’s solicitude. He gives voice to his son’s deepest anxieties. It is as if he knows, through cruel intuition, exactly which wounds to attack. “Good thing a father doesn’t need to be taught to see through his son,” he says. Finally, he passes judgment: death by drowning. And in the story, word becomes deed.

Beau is Afraid is Kafka for the present. In this version, the powerful father, which we’ve long done away with, has been swapped out for a girlboss mother. The protagonist is paralyzed by anxiety from the beginning, his world bent by paranoid fear. He goes to therapy to gain the confidence to work out his problems, but despite his efforts, things tend to turn out as badly as possible. Catastrophes pile up like in cartoons. If Kafka’s protagonist struggles to write a letter and turns to his father for support, Beau cannot make it to the airport without calling his mother. If Georg’s father criticizes his promiscuity while overwhelming him with virile power, Beau suffers from a fear of sex so overwhelming that it becomes a death sentence.

When Beau explains that he’s not going to make his flight home, his mother doesn’t berate him. She doesn’t destroy him with bitter vitriol. She simply tells him, in a voice lowered to a whisper of disappointment, that maybe it’s best if he comes another time. The voice of the understanding parent is perhaps even more devastating than that of a cruel one.

The film does not depict a life or death struggle with a symbol of authority through which an autonomous individual is born. Instead, we have a person who is perpetually the victim of events beyond his control, a figure who has been reduced to near total passivity after a life of aimless indecision. This is ultimately why his mother, disgusted by her son’s life of wasted potential negated by fear, passes judgment on him. Despite her love, he’s still sentenced to death by drowning.

The Brood’s Nola Carveth (Samantha Eggar)

Nola Carveth is in an inpatient psychiatric facility under the care of Dr. Raglan, a pioneer of “Psychoplasmics,” through which patients’ repressed traumas manifest physically. (One man grows tumorous gills on his neck.) After a recent visit to see her mother, Nola’s five-year-old daughter, Candace (Candy), returns home to her father Frank covered in bruises and scratches.

Frank decides to investigate and discredit Raglan and his methods. He leaves Candace with Nola’s mother, who is bludgeoned to death by an intruder; Candace is unharmed. Later, Nola’s father is killed in his home in the same way. In both cases, the perpetrators are child-sized creatures who lack belly buttons. It turns out these monsters are born of Nola’s rage and act on her fury. Through role-playing therapy sessions, we learn that Nora’s mother abused her, and thather alcoholic father looked the other way. Their psychoplasmic comeuppance was inevitable.

Frank finally breaks into the institute himself and Nola reveals to him the results of her treatment: she has grown a sac-like external womb, which she tears open with her teeth to birth her rage-babies, who she then, like a true mama bear, licks clean. “I’d kill Candace before I let you take her away from me,” she tells Frank. Shocked at what his wife has become, he kills Nola and, after significant carnage, he escapes with Candy—who herself now has worrisome growths on her arm.

One could see The Brood as a misogynistic manifestation of male disgust at pregnancy, childbirth, and mothering—the physical transformations, the symbiotic bond between mother and child, the resulting alienation fathers may experience.

Yet Nola is a sympathetic character. She seems unaware of the violence her brood has done, and she’s ultimately a victim of a paternalistic psychiatrist who uses her to test his theories. She only becomes a destructive broodmare under duress. The Brood is a warning about what happens when women don’t choose.

Anatomy of a Fall’s Sandra Voyter (Sandra Hüller)

In the opening scene, a successful author, Sandra, is flirting with a younger woman interviewing her, when her husband interrupts from another room, playing an irritating instrumental version of the song “P.I.M.P.” on repeat. The interviewer leaves, and the couple begins to argue, and the couple’s blind, 12 year old son goes for a walk with his service dog. When the boy returns, he and his dog find his father’s body in front of the home, dead, having fallen from the house’s upper window.

There is an inquest and a trial revolving around the question of whether the husband was depressed and killed himself or whether, in the conflict while their son was out, his wife pushed him out a window. Questions emerge about the marriage during the trial. What was the true nature of the couple’s earlier fights? What did the wife’s success mean to a husband struggling in the same field? It is revealed that the son’s blindness was caused by a childhood accident: he was hit by a motorcycle. Is this evidence of Sandra’s maternal neglect and self centeredness, is it a source of suicidal paternal guilt?

The son sits through the trial and hears Sandra testify that his father tried to kill himself with an overdose of a specific medication. This prompts in the boy a memory from before the fall. His dog had been sick for several days after coming across his father passed out. The boy does an experiment, giving the dog the medication, to see if what he came across was his father’s passed out body after the attempted suicide that his mother described. The dog gets sick in a way the boy remembers from before the fall. It is this testimony about his memory and the experiment that clears his mother of the charge of murder.

But is the boy’s experience a moment of après coup? Did new knowledge from his mother’s testimony help him make sense of an experience he could not have understood before? Or were his testimony and his experiment an artful and devastating manipulation of his own memory required by his attachment to his mother? The dead father’s fall and the marks it leaves become an ink blot test for our ideas about ambitious, sexual, engaging mothers, the truth of the stories they tell, and the ways that we tell stories with them.

Volver’s Irene (Carmen Maura) and Raimunda (Penélope Cruz)

In an important scene in Pedro Almadóvar’s Volver, the apparent ghost of Irene sits up in bed with her granddaughter Paula and explains to her why she and Paula’s mother Raimunda did not live together. She tells her that they were a poor family and that Raimunda pulled away from her as a teenager. Irene hides the dark truth behind Raimunda’s departure, telling Paula that she did not know why their relationship deteriorated. What she wanted to communicate was the special nature of the relationship that exists between mothers and daughters and the pain it causes when it breaks down. “Es muy doloroso si una hija no quiere su madre”: “It really hurts when a daughter doesn’t love her mother.” Irene implores Paula to love her mother, enough so that she can feel it.

The real reason for Raimunda’s departure is that she was raped by her father, resulting in her pregnancy with Paula. Raimunda is both Paula’s mother and her sister, a very Chinatown discovery. This doesn’t come as much of a surprise: the men in Volver are no good. Rapists and abusers at worst, deadbeat losers at best. Earlier in the film Raimunda’s husband Paco attempts to rape Paula, claiming that it is okay because he’s not her real father. Paula stabs him to death in self-defense, and Raimunda cleans up the mess. Likewise, after Irene discovers the truth about what her husband had done to Raimunda, she burns down their house, killing him and the woman with whom he was having an affair. The police confuse the woman’s remains with those of Irene, and she exists as a ghost up to the moment of her confession. These men do not matter. The police never suspect any foul play with the fire, and there is seemingly no search, nor any concerned family members in the disappearance of Paco.

In short, Volver is a kind of liberal girl power story. It is also an early depiction of intergenerational trauma, which has since become an indispensable concept to contemporary therapy culture. But there is something nonetheless deeply moving in the relationships between these women across generations. Almadóvar’s mothers are not the idealized “good breast.” They are flawed. But when they discover the truth of the father’s incestuous desire, they are ready to sacrifice their own lives to make amends.

Volver ends with a new beginning. Raimunda embraces Irene and says that she has so much to tell her. She wonders how she could have ever lived so long without her. There is a shared excitement, a borderline frantic energy. Mother and daughter are reunited and practically overwhelmed by the possibilities in front of them.

Mother’s Mother (Kim Hye-ja)

Bong Joon Ho’s Mother tells the story of an unnamed but overprotective mother whose life is completely devoted to her mentally disabled son, Do-Joon. She follows Do-Joon around town to keep him out of trouble. She cleans up after him and lobbies for his interests. She sells medicinal herbs and operates an illegal acupuncture practice to make ends meet, telling her patients that she knows a special point on the inside of the thigh that can cure them of painful memories. Do-Joon is often mocked for his disability, which throws him into fits of violent rage.

One night, after getting drunk at a local bar waiting for a girl who never arrives, he decides to follow a high school girl he sees on the street. She disappears around an abandoned building, and the next morning she is found dead. Do-Joon is arrested, and the rest of the story follows the mother’s neo-noir detective odyssey to prove her son’s innocence. The problem is that the more she searches, the more her sense of her son’s innocence is cast into doubt.

Most mother stories revolve around the emergence of the child’s autonomy from parental authority, but Mother depicts the protagonist’s painful recognition of the need to escape from her own maternal love, whose boundlessness threatens to swallow her. In her search for the truth, she encounters a great number of different people, almost all of whom lacked the protection that she has lavished on Do-Joon. But she cannot be a mother to all of these children. In fact, she must sacrifice them if Do-Joon is to be saved. Near the end of the film, she learns that the police have released her son. They found the “true” killer—the murdered girl’s boyfriend.

In the final scene, there is a moment of catharsis. The killer also suffers from a mental disability. In him, the mother recognizes Do-Joon. She cries not only because she is powerless to alter his fate, but also because no one else is coming to help him.

3 Women’s Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall)

One could hardly imagine Millie, one of the titular characters of Robert Altman’s 3 Women, as a mother. A woman possessed of an uncanny degree of self-absorption, she seems incapable of even the most minimally generative social contact. This does not stop Pinky, another of the three, from confronting Millie with one, wide-eyed question: Are you my mother?

At first, Millie seems constitutionally unfit to respond with warmth to Pinky’s sycophantic attention. Shortly after moving into Millie’s apartment, Pinky tells her, “You’re the most perfect person I’ve ever met.” Millie seems unbothered by Pinky’s devotion, either through blindness or indifference, until one day she makes Pinky the cause of so much grief and harshly dismisses her.

With this rejection Pinky turns away from her object of adoration and undergoes a startling transformation. She is suddenly so much of what Millie is not: charm, independence, sass, sexuality. Millie is in turn transformed by Pinky’s new persona. Dislodged from her maternal position, she finds herself floundering. Bereaved of her child she becomes child-like herself.

In her new, freer garb, Pinky rises to social and sexual prominence in a way that Millie could not, but at its height, independence overwhelms her and it all comes crashing down. She returns for Millie’s embrace at the very moment that Willie (the third, pregnant woman haunting the background of the film) goes into labor. The pair of women rush to help her in the delivery, but it’s too late. The child is stillborn.

In the final scene, a delivery man asks for a signatory, and Pinky tells him, scampering off, “I’ll go get my mother.” Millie returns to sign, and the exchange reveals that the women have killed Edgar, Willie’s laggard husband and the only would-be father of the film – they don’t need him. Millie leads Pinky and Willie into the house for supper, ordering them around in a motherly tone. A tidy solution to the unwieldy demands of sexuality, the film demonstrates the power of maternal transference and interpolation, and precisely how, together, three women can a mother make.