Daydreaming at the Sex Conference

The psychoanalysts are still thinking about sex, but somehow the thing itself has gone missing.

Returning to your hometown to attend a psychoanalysis conference may sound regressive, but I’ll let my shrink decide. That conversation will have to wait, though, as my shrink is attending too, and we decided to be strangers during the three-day affair, which I learn is a common arrangement.

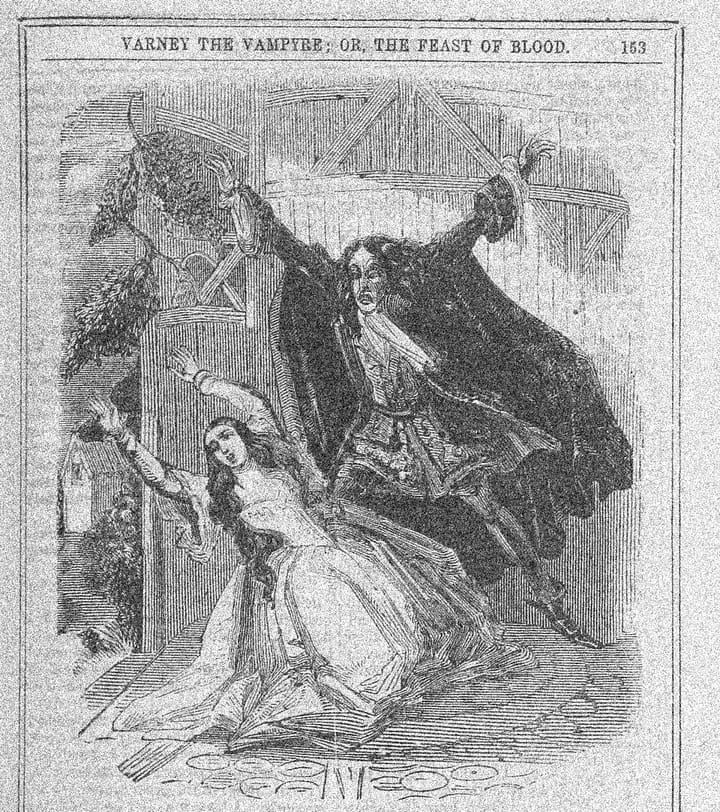

Despite any feigned estrangement, on the first day there abound exclamations and hugs between those who studied and worked together, and maybe only see each other at conferences now. The 36th Annual Spring Conference of Division 39: Society for Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychology is held at the Westin Hotel in downtown DC, and the theme is “Sex.” Thinking about sex in DC, or the kind of sex that is most DC, brings to mind rumors of name-brand politicians acting out compulsions and perversions in swanky hotel rooms. Libertine politicians, in turn, evoke the work of the Marquis de Sade, whose shadow looms large in the keynote lecture, to be delivered by Avgi Saketopoulou, titled “Sadisms: Risk and Ruse.” The program’s preference for marginal, perverse sexualities—BDSM, sex work, kink—makes clear that this is not your mother’s psychoanalysis conference (if that’s possible).

On the opening day, the beige meeting room is packed, and many sit on the floor for Ann Pellegrini and Avgi Saketopoulou’s talk on their book Gender Without Identity (2023). The couple intervenes in the controversy over trans kids by agreeing with the transphobic right that transness can be a response to trauma. However, the pair follow a very different theoretical premise: that trauma underlies all gender, and can be “a generative energy for crafting the self,” per Saketopoulou. Psychoanalysis has always theorized the emergence of “normative” gender out of the polymorphous perversity of infant sexuality, a process which entails the symbolic violence of cultural constraints. The idea that trans kids are “broken” relies on the myth that any other self was not broken into their gender. Saketopoulou and Pellegrini had deliberated whether to publish a theory that may be co-opted by the opportunistic Right, but, the former says, “at the end of the day, you have to take the risk.” This also meant breaking from the liberal orthodoxy that trauma has nothing to do with transness, that queer people are born that way: “Liberalism is more perniciously violent because it doesn’t understand its own violence,” Saketopoulou avers to a wave of illiberal nods.

The commencement ceremony takes place in a capacious gray-and-cream auditorium, and opens with addresses by the conference’s two lead organizers, Jessica Chavez and Jessica Joseph. Beyond endless citations and reading lists, the Jessicas share their intention for the conference to be “an aesthetic experience—to play, and to move our attendees,” and an invitation into a “liminal play-space.” Lara Sheehi, the president of Division 39, noting our situation in DC, refers to the failures of the US government—on the genocide in Palestine, on Roe v. Wade, on climate change—and hopes we can “reality-test” together, against that backdrop. Sheehi wears a keffiyeh, as do many in the audience. In the absence of a code, the audience’s dress ranges from business casual—neutral button-downs and jackets—to more queer iterations of knitwear, ponchos, overalls. There’s less all-black than I expected, and, relatedly, I find myself alone when I step into the courtyard to smoke.

In the lobby outside the ceremony, graduate students present their research on poster boards, alongside roving plates of deviled eggs. Disarmed by the scientific style of presentation, I realize, to my horror, that quantitative research is on display. I discuss the “tension” between quantitative and qualitative research with a student from Montréal, whose research quantifies “alexithymia,” meaning the inability to recognize or describe one’s own emotions. I offer that qualitative research cannot really be displayed on a poster board, and she points to a poster board behind me that does the same. Trying to read the small text about mermaids and dream-analysis through a half-circle of analysts clutching cocktails, I decide that qualitative research should not be presented on poster boards. I left feeling unquantifiably alexithymic.

The hottest historical analyst at the conference—and the only one to have a talk devoted to him—is, of all people, Jean Laplanche, prodigal son of Lacan. In brief, Laplanche held that the parent’s acts of care to their infant are parasitically loaded with the parent’s sexual unconscious, which becomes implanted on the infant’s body and mind as “enigma,” a never-ending riddle. The infant translates enigma into ego, but there is always an untranslated remainder that constitutes the unconscious as infant sexuality, whose press for translation is the sexual drive. Here, psychic life is about endless translations of enigma, rather than limited interpretations of repressed trauma and perversions. For how incestuous and infantilizing this theory may sound (and impossible to quantify on a poster-board), it’s also weirdly liberating, as it suggests everything about you can be retranslated. A major aspect of Saketopoulou’s project is retranslating Laplanche into an American context starved of erotic enigma.

Day Two

Day two, Saketopoulou takes the lectern in the auditorium in a zippered leather jacket and rectangular black glasses accented by her arched brows. Saketopoulou’s aura—mingling professorial poise with dominatrix intensity, an affinity for motorcycles with tattooed arms—carries an edge of Kathy Acker, down to the title of her piety-shattering Sexuality Beyond Consent (2023). This work develops “exigent sadism” as an ethical framework for practices that transgress limits to allow for ego-dissolved experiences of the unknown—in Avgi’s phrase, “the opaque”—within oneself and the other. Perverse eroticism (in kink and art) is especially conducive to these limit experiences, because perversity activates the anarchic energy of infantile sexuality, dysregulating the ego and unbinding poor translations of the self, to allow new selves with greater psychic freedoms.

In her keynote, Saketopoulou explains that, while Sexuality focused on the erotic and aesthetic dimensions of exigent sadism, her next project will develop its political and clinical uses. A chair behind her displays a pinkish flag printed with “Sade,” credited as “the most insistent and persuasive author on how the erotic and politics entwine.” The link between Sade and psychoanalysis is well-established, as when Simone Beauvoir hailed him as “as a precursor to psychoanalysis” in her essay “Must We Burn Sade?” From the ashes of Sade the problematic libertine, Saketopoulou resurrects Sade the queer revolutionary, with sadism repackaged as a kinky ethics of care. Saketopoulou outlines the theoretical drift that has neutered psychoanalysis: since Melanie Klein, treatment has focused on repair, and reparation cleaved eros from aggression (contra Sade), which has desexualized psychoanalysis. Reparative analysis, under fantasies of healing, safety, and stability, encourages the ego’s complacency with harmful relations and institutions, mired in the “molasses of dialogue,” whereas exigent sadism recognizes the irreparable, and may draw on the libido’s edge to sever such relations. (Saketopoulou notes that she has disaffiliated from multiple institutions in the past year over trans rights and free speech on Palestine.) “Refusing the reparative gesture,” exigent sadism holds that trauma cannot be healed any more than the unconscious can be cured, that decisive action begins beyond repair. There’s the idea that psychoanalysis has to give up its weird sexual hang-ups to become politically useful, but Saketopoulou argues the opposite: “the political force of psychoanalysis lies in the libido.” Only when analysis claims its libido, with all its sadism, can repair give way to revolution.

Saketopoulou veers into how reparation for the “wound of antisemitism” is weaponized in the ongoing genocide in Palestine. The auditorium hums with rapt attention, and one has the feeling of witnessing a historical event in institutional psychology, a calculated disruption like the Velvet Underground’s sonic assault against the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry in 1966. I suspect that many in attendance disagree with Saketopoulou and clutch their pearls at the recuperation of sadism, but at the Q&A, there’s no real pushback. However, afterward several panelists in other talks are still “grappling” and “digesting” the keynote, appreciative of the provocation but unclear about clinical applications, and at least one seems at a loss now that “we’re not supposed to repair.” Exigent sadism, darkly compelling in eroticism, risks becoming overstretched in the clinical and political. Saketopoulou claims to counter the Kleinian taboo on severing relations, but therapy already widely encourages clients to cut off their “toxic” family members and friends, as if people today suffer from too many relations, rather than mass loneliness. Further, the last thing the Left needs is more internal divisions, and the advocacy of severing (familial) ties does no favors to the perception of psychoanalysis as a cult. In any case, whether sadistic or cultish, the circulating ideas about the unseemly underside of psychic life feel especially liable to detonate in the context of a city as reliant on ego and reason as DC, the proverbial belly of empire, the Death Star whose short wick of sanity hisses away.

Possessed in DC

My favorite movie about DC is The Exorcist (1973), which locates the devil in Georgetown, the whitest and wealthiest neighborhood in the city. Regan, a 12-year-old girl, becomes possessed by a demon after playing with a Ouija Board. After consulting doctors and psychiatrists, Regan’s symptoms become so alarming that her mother Chris calls on Father Damien (who’s also a psychiatrist) and insists Regan needs an exorcism—no other therapy will do.

Psychoanalysis is, in a roundabout way, a form of exorcism, although members of Division 39 may disagree on whether treatment means casting out the demon (by summoning it to consciousness), or working with the demon, channeling its limitless energy, because it can’t be cast out.

Regan’s possession makes her hypersexual and sadistic: she grabs her hypnotherapist’s crotch and tells the exorcizing priest to “stick your cock up her ass.” She is on the brink of puberty, so there’s the suggestion of puberty as sexual possession, ending the halcyon innocence of childhood. Playing devil’s advocate, psychoanalysis counters that the girl was sexual since infancy, and that puberty actually makes sexuality less demonic—focused on the genitals, relating to others as whole beings, intent on relationships and procreation. Laplanche refers to the “demonic aspect” of infant sexuality, and it’s as if this demon makes a last revolt before puberty can repress it. The psychological horror of The Exorcist may be that the melodrama (and all the goo) hardly require possession, only the violent overthrow of the ego’s resistances to the demon that lurks in every psyche. The Ouija board is just the alibi the film needs to assure the viewer that, after the exorcism, the demon has been removed, not merely repressed; that thankfully, impossibly, she doesn’t remember any of it.

I went to an all-boys Catholic high school in downtown DC, not far from the Westin, where Jesuits like Father Damien worked. When I tell other people from DC where I went to high school, they usually laugh, feign disbelief, ask me why I didn’t transfer, recount some traumatic experience at a dance. I say it wasn’t that bad, though it was far worse than they could know. I spent 2022 trying to get sober in DC and lived in a group house in Georgetown, where I ran up and down the Exorcist steps (if you can’t afford analysis, there’s always exercise). In 12-step meetings, I met other alumni from my high school—others who had failed out of New York, who were hopelessly manic-depressive. I wondered whether we were pathetically similar, licking the same wounds, or if I was just projecting. Walking back from the conference on the first day, I saw a former classmate staggering alone toward the Capitals game, and imagined he had become another miserable alcoholic. Then, looking back, I realized he had used a wheelchair in high school, and had since regained the ability to walk. I was the miserable one.

Day Three

On the third and final day, there is a keynote conversation between Da’Shaun Harrison and Joy James. James, a professor and abolitionist, discusses how the public figures who narrate black death today, usually bourgeois millionaires, pale in comparison to the last century’s “roll call” of assassinated black rebels and ancestors (Malcolm X, MLK, Fred Hampton). On the perils of celebrity activism, she asks, “What happens when you see your persona as a resistor sold back to you?” It’s like activism has become too safe. In the audience, Saketopoulou holds a banners that reads, “Fuck Safety One Day At A Time”; in Sexuality, she writes that safety can be “a danger the costs of which are incalculable: one can measure what went wrong, but one cannot measure what never became, what one never got to experience.” James notes that there are 70–90 cop cities today, where militarized police are training with the IDF—Atlanta police have done so for almost a decade, Harrison says—so that “there will never be another mass resistance to police killing in the US.”

I attend talks on “Blighted Phenomena” and “Phallogocentrism” and begin to feel the boredom inherent to conferences, but it’s the boredom of the porn addict—yawning to mentions of oversized phalluses and overheated clinical liaisons. There has been little discussion about how technology is changing sexuality, and, as if out of spite, the wireless mics are wildly unreliable. At the end of the day, I sit down with two PhD students from Pittsburgh, Anna and Michael, and we talk about what was overlooked in the program, whether the emphasis on taboo sex made a taboo of more vanilla sexual concerns (like how to have it at all), or whether all the perversity crowded out sex that was neurotically normal. Michael says, “as much as it’s been around sex…, I don’t think I’ve heard anybody talk about sex itself.” Anna, referencing Adam Phillips, points out that “anyone who’s having sex with anyone creates sex for themselves, so it’s presumptuous to talk about sex, because it doesn’t exist before it’s created.” And she questions “talking about BDSM as a prism to knowledge, an ontological framework…. What is that doing for everyone?”

On the question of what made this conference different from previous ones, Michael says “the older generation is notably absent,” an absence that was noted in talks, without speculating why. The relative youth of those present seemed to bend the politics and interests of the conference toward the queer Left; unsurprisingly, the conference concluded with a surprise drag show.

Sex Deficit

On the surface, the conference represented a return to the origins of psychoanalysis (in sex and perversion) while also a widening of the political and generational fissures in the field. I don’t think this was accidental: Saketopoulou was clear that the sharp edges of exigent sadism apply to relations within the field as well. Under the civility and upbeat mood, I felt the stirrings of a wartime psychoanalysis that, in the context of raging culture wars, police violence, and a genocidal war abroad, had to take a side and jettison old fidelities to safety, dialogue, and repair.

Many of the talks addressed transgressive sexualities, so I’m left wondering: why did it all feel so deeply unsexy? Granted, the conference format is not an aphrodisiac (except perhaps in 120 Days of Sodom), but there was still room for some horribly perverted case study or wet dream. Sexual practices that test people’s limits were broadly embraced, but these discussions themselves obeyed political limits (relating to race, gender, identity checkmarks), charged with a more punishing taboo. It may be true that for psychoanalysis to be political, it needs to have a libido; but by the same token, for psychoanalysis to have a libido, with all its perversion, it needs to include inconvenient, impure politics. Division 39 won sexual transgression at the cost of political conformity; imprisoned for libertinage, Sade was freed by the revolution, only to be reimprisoned for his politics. But maybe some people should be in prison—James said as much about the January 6 rioters.

Even within sexuality, only select perversions (and perhaps not the most common in the clinic) were attended to, and these felt a little safe, meaning hardly taboo. Take the example of BDSM. I doubt that BDSM retains much of a taboo among young people today (sex researcher Aella’s poll on the tabooness of fetishes found that giving and receiving pain ranked around 2 on a 5-point scale), and any persisting stigma around the subculture may have less to do with risk or perversion, and more to do with seeming a bit nerdy and autistic (although Sexuality does provide authentically moving accounts of such practices). Concerning the depiction of sexuality in Sade’s work, Beauvoir writes that it suffers from “autism” in its total neglect of anything like “emotional intoxication” or real intimacy—characters merely use other bodies for anatomical inquiry or masturbatory sex that leaves the ego as ironclad as the prison walls in which Sade wrote. And in a perhaps unintentional sadism, the conference, for all it had to say about sex on the margins of polite society, was relatively quiet on emotions and love. Affect seemed to have dropped out the bottom of queer theory. There was no talk devoted to romance, though there was one on “Sex on the Spectrum.” When this headstrong psychoanalysis burst open the taboos on sadism, sex work, race play, it also lost romance, emotion, mundane intimacy, like so much collateral damage. Abstract discussion of perversion drained of emotion proved dry ground for desire, as in Sade’s fiction, where the absolute disrespect for taboo eventually empties the transgression of any thrill.

To try to understand what I felt to be missing from the conference, why I left unscathed despite my Catholic triggers, why there was so little squirming in seats, I turned to the program for the 1997 congress of the International Psychoanalytic Association (founded by Freud), whose theme was “Psychoanalysis and Sexuality.” As recorded in the IPA’s journal, the congress included panels on: “The Analyst’s Sexuality,” “Impotence and Frigidity,” “On Seduction,” object love, “Sexuality in the Age of AIDS,” “On Perversion," adolescent sexuality, biology, “Highly Erotic Transferences,” Gaudi’s architecture, “The Oedipus Complex Reconsidered,” “Sexuality and Somatic Illness,” “Castration as an Organizer of Bisexuality,” pornography, “Narcissistic Influence on Erotic Love.” This program is less specialized by identity, offers broad overviews of foundational concepts, and speaks more to the most prevalent sexual problems of the American public today than does Division 39’s program. It also just sounds a bit sexier. For Division 39’s laudable readiness to discuss race and queerness, more classic analytic problems (some more unresolved now than ever) like incest, fetish, seduction, neurosis, and sexual performance were strangely neglected, like political non-starters. But the two programs also overlapped at an unlikely and perverse point.

In her keynote, Saketopoulou, as a critique of Zionism and Holocaust exceptionalism, discussed the need to recognize the enigmatic in the Holocaust to allow varying narratives about it to emerge. Like the enigma in the individual, there must remain something enigmatic about any historical trauma that can never be assimilated, that presses for new meanings, fantasies, questions. Using enigma to multiply versions of the Holocaust counters “a very particular version of the Shoah that could be used to legitimize a militant and expansionist Zionism,” as Pankaj Mishra writes in "The Shoah after Gaza." The suggestion of the enigmatic within the Holocaust was easily the most transgressive moment at the conference (though anti-Zionism was widely represented and discussed), like psychoanalysis venturing into a forbidden zone. Saketopoulou began this tightrope-walk in Sexuality with her analysis of the film The Night Porter (1974), a controversial psychodrama about the erotic relation between a concentration camp guard and an inmate that outlasts the war. The film shows, she writes, “there is a possibility for erotic relations that are not accidental but emerge precisely from the material circumstances that confound them,” that even world-historical trauma can find erotic expression between individuals. In The Exorcist, released a year prior, Chris’ director provokes her German butler: “Was it public relations you did for the Gestapo or community relations? And you never went bowling with Goebbels either, I suppose? Nazi bastard.” The suggestion is that the butler may be repressing an evil past that simmers just under the surface, ready to boil over—he later assaults the director in the kitchen.

Saketopoulou’s provocation was surprisingly precedented: at the IPA conference, a panel on “The Holocaust” discussed the effects of the Holocaust on the sexuality of survivors, perpetrators, and their families. The panel report includes the case study of a man who became a hero in the Polish resistance after his family was murdered, and who was referred to analysis after requesting sex reassignment surgery. He had developed “an unusual perversion”: while getting a shave from a barber, he complained repeatedly that it wasn’t smooth enough, until the barber drew the razor over his neck, which would cause him to have an orgasm. Here is a case, queer and masochistic, of a perversion inexplicable except by analysis, that underlines Saketopoulou’s point, and it was exactly this type of perversion I couldn’t find at the conference. Instead of analyzing a hyper-specific perversion to reveal a general truth—“To reconnect traumatic experience with his internal world, the patient has to revive a relationship to his parents—to bring the dead to life”—the panelists were more likely to take a widespread, “taboo” practice (polyamory, drag), and argue why it was actually affirmative and liberatory for those who practice it. Plenty of politics, but little on the real dilemma of perversion, like when it leaves your pants a mess at the barbershop.

At the Sex conference, it was as if the Division had lost touch with any sexual pathology that analysis could treat. Symptoms were traced to political causes (transphobic legislation, the oppression of Muslim women), or transformed by theory into empowering kinks. In the turn away from sexual pathology and treatment, psychoanalysis finally forfeits its contested status as medicine and becomes a forum for political theory and queer activism. The historical antipathy between medicine and queerness, in which psychoanalysis has been complicit (the IPA program includes papers like “A FE/Male Transexual Patient in Psychoanalysis”), explains why psychoanalysis would drop the former to embrace the latter. But an overcorrection for medical pathologization runs the risk of dismissing a symptom and the problems it creates so long as the symptom leans queer or kinky (in which case it should be celebrated). Meanwhile vanilla problems (impotence, anhedonia) may as well be ignored, or referred to an actual doctor. At the conference, the turn away from medicine also meant that the question of medication was wholly avoided, even though medications are a main cause of sexual problems today (look no further than the meme of a poolside LeBron James in ecstatic disbelief about his Zoloft-induced asexuality). If straight psychoanalysis misdiagnosed queerness as perversion, queer psychoanalysis downplays the idea that any perversion is a problem worth analyzing. I, for one, do not attend the psychoanalysis conference to celebrate my queerness, but to measure my sickness, searching for words to rouse my demons. And if incest doesn’t come up, I want my money back.

■

Christian Prince is a neurotic writer living in Paris.