The Guardian That Never Sleeps

For almost ninety years mass anxieties about kidnapping and child abuse have driven the development of surveillance technologies focused on seeing and hearing children. How might these technologies impact the relationships between mothers and children?

A “Radio Nurse” now brings the nursery into the living room, kitchen, or any other room desired. When a child is sleeping or playing in a room when no older persons are present, every sound within that room can be transmitted to any spot in the house. The outfit consists of a pickup unit, placed near the child to be “watched,” and a loudspeaker which can be placed in any convenient location.

1937 Zenith Radio Nurse Advertising copy

In his recent essay “The Stork,” psychoanalyst Stephen Hartman describes visiting his newborn niece in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) of an upscale New York City hospital. He finds the baby wearing a plastic ankle monitor of the sort created to track pedophiles on house arrest. He learns from the parents that one of these devices is placed on every baby in this NICU to prevent kidnappings. While no actual kidnappings have been attempted, some parents and hospital attendants have, at times, failed to pass a baby over to the desk nurse on the way out of the unit, so that she can deactivate the ankle monitor before they leave. These failures lead to a lock down. The elevator seals to trap whoever is with the baby. Alarms sound, and the unit is impenetrable until the baby can be safely returned to the nurse at the front desk.

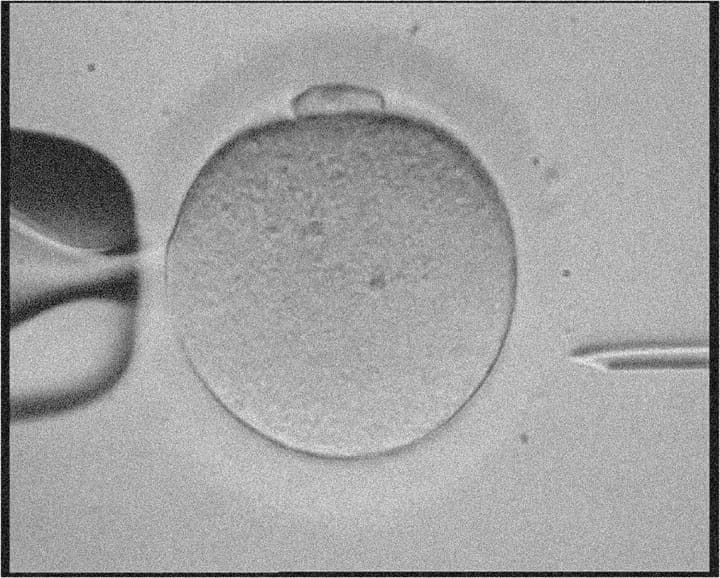

Infant ankle monitors can be found in NICUs across the country. Such surveillance technology has—without much thought being given to what it means to developing children, the experience of parenting, or the parent-infant relationship—become an ever-present fact in the social matrix that is contemporary child-rearing. What might the presence of these new forms of tracking and watching mean to the experiences of mothering and of being an infant?

D.W. Winnicott, pediatrician and psychoanalyst in wartime and post-war Britain, developed from his observations of mothers and babies the concept of primary maternal preoccupation. Infants get a good enough start, psychologically speaking, when their first days and weeks involve being held, in mind and also physically, by a mother who, enough of the time for her baby, can be relatively free from the pressures of reality and in a state of boundaryless attunement to the baby’s needs and rhythms. This attunement is more or less a healthy psychotic state, an “at-one-ment” between baby and mother that the father or the paternal aspects of society should respect and serve to protect. External pressures on a mother to think too much about the concerns of reality in these first days with her baby constitute intrusions into the relationship that forms the bedrock of later emotional experience. When intrusions occur during this period they create within the field of the mother-child relationship intense responses that can return later in the infant’s life as lack of bodily integration, feelings or fears of falling without end, depersonalization, a loss of a sense of what is real, and a loss of relational capacities. In the 1970s, hospitals incorporated the understanding of the infant-parent relationship that grew out of the work of analysts like Winnicott and the analyst and attachment researcher John Bowlby, and incubators in NICUs became equipped with ports that allowed for touch and contact between caregivers and their premature infants.

In the case of incubators, psychoanalytic research provided key insights that led to changes in the use of a life-saving technology to better meet the needs of infant-parent dyads. In the case of ankle monitors, anxieties about very unlikely events (baby theft) have been met with a technological fix that gets in the way of the infant-parent relationship. A newborn needs a mother who can attune to his or her biological rhythms, and a mother needs to be able to help modulate those rhythms with a sensitively attuned body of her own. This process requires maternal attention that can be free to wander creatively while experiencing her baby. Ankle monitors interrupt this process by inserting unnecessary demands on mothers’ attention, and false crises into the dyadic relationship.

Surveillance technology doesn’t just intrude into the mother-infant relationship; it also creates a social ideal of an omnipresent mother whose hearing, gaze, and ability to protect her child are extended into parts of childhood experience once private or navigated alone, or where the mother once arrived to help only after injury or harm. Maternal perceptual capacities are extended by surveillance technology at specific historical moments. Maternal hearing was technologically extended in 1937 with the advent of the baby monitor. Maternal sight was technologically extended in 1992 with the arrival of the nanny cam, and yet again in 1996, when nanny cams began to send information over the internet. Maternal knowledge of the location of a child shifts from relying on neighbors, teachers, and others in a community to the use of geolocation as the market for wearable tech and cell phones boomed from the 2010s onward. Maternal capacity to read children’s emotional states is now being extended by the incorporation of AI into nanny cam technology. These technological extensions do not just allow for multi-tasking or increased perceptual abilities for mothers; they also create new ideals and anxieties about what is being noticed and how.

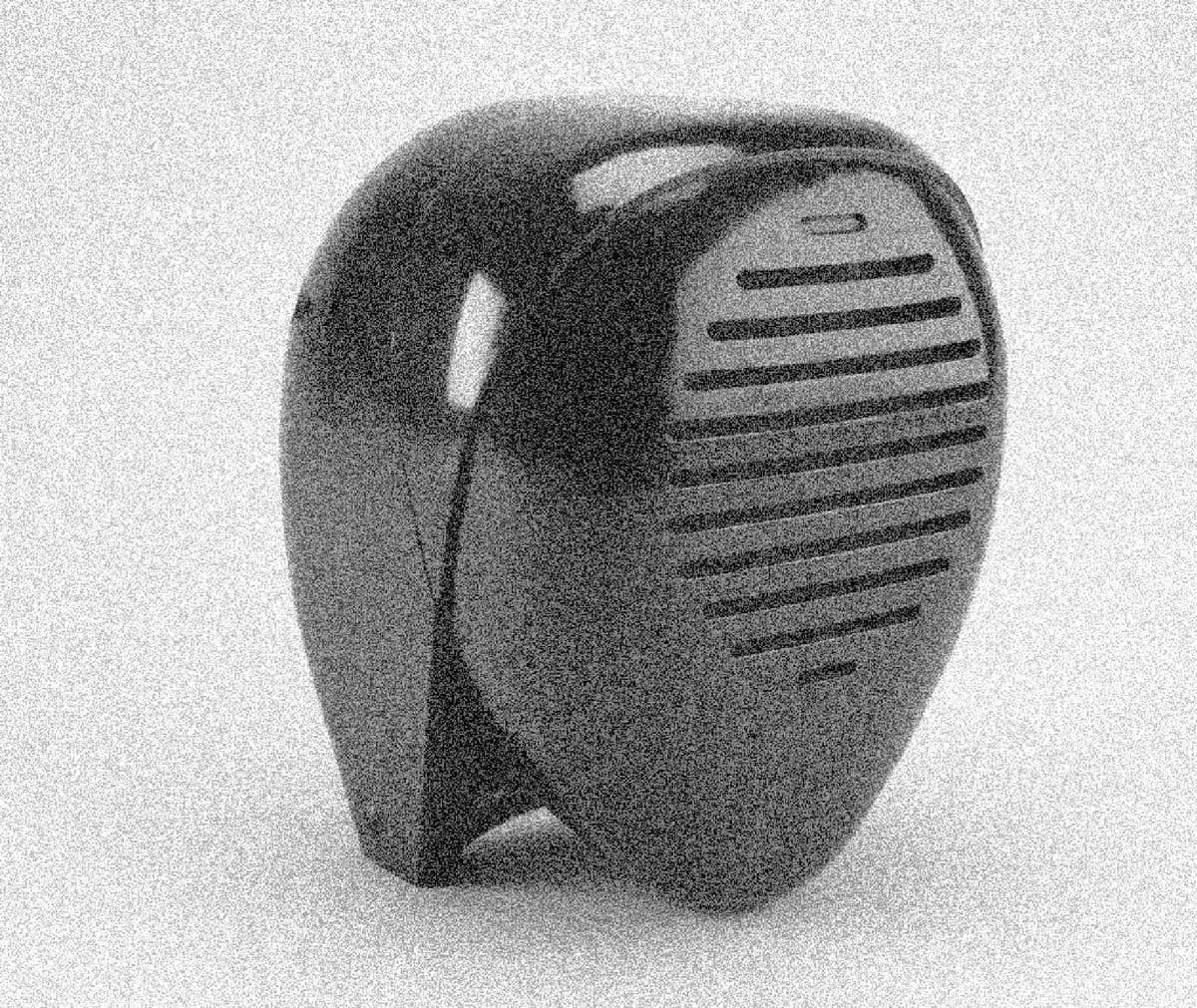

The first baby monitor, the Zenith Radio Nurse, came onto the market in 1938. Designed by Isamu Noguchi, it was made up of two parts: the Radio Nurse Receiver, a mahogany-colored bakelite modernist abstraction of a female head whose facial features are replaced by a grill that conceals a speaker, and the Guardian Ear Transmitter, a white enameled metal microphone, far less elegant and not at all anthropomorphized. The brown Radio Nurse stays in the room with the parents, while the white Guardian Ear stays in the room with the infant. An advertisement for the device shows a pretty young blonde mother entertaining at a dinner table turning to attend to the sounds from the disembodied faceless head on her shelf. The mother’s ability to hear between rooms now allows her to entertain guests without missing her child’s needs. The mother’s attention can now be in two places—she can ensure her husband’s upward mobility by properly attending to the needs of his boss and the boss’s wife when they come to dinner, while not missing any calls for care.

The device was brought onto the market during a period of mass middle-class anxiety about child abduction triggered by the 1932 kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby and the ensuing manhunt and trial, which ended in the execution of Bruno Richard Hauptman in 1936. Upwardly-mobile parents had a technological fix for the fear that their babies could be stolen and killed by greedy foreigners. What shifts in the infant-parent relationship might this new technology have ushered in? For this generation of babies, we can imagine that a new set of expectations regarding care began to emerge. The baby with an Ear Guardian (aspirational or real), compared to one in an earlier generational cohort, experiences a delayed encounter with the reality that mother is not omniscient, that she cannot hear him calling if she is away and he is not loud enough. It creates in the baby’s imagination and in the social imagination a mother who should hear something she was out of the room for, a sound or tone quieter or more subtle than one ought to expect a person who is away to pick up. The service manual for the Radio Nurse recommends holding a watch to the Guardian Ear and tuning the trimmers until the ticking of the second hand can be heard in the other room over the Nurse Receiver.

The first “nanny cam,” a camera specifically designed and sold for monitoring not just children, but especially the people hired to care for children, was invented in 1992. This is the year marked by some as the high-water mark in the social panic over “Satanic Ritual Abuse,” a mass-paranoid phenomenon that began to be debunked in 1987, but only really lost popular steam between 1992 and 1995. The nanny cam was one of the earliest video technologies—along with the Axis Net-Eye 200 in 1996—to have an internet protocol that allowed video to be transferred via a networked computer and not require a closed circuit system. By the 1990s, Reaganomics had done its number on the social fabric of the United States, and the Clinton Democrats had continued policies advancing the Thatcherite neoliberal consensus that there “was no society, just individuals and families.” The need for low-cost child care was just as pressing as the suspicions being levied at those who would provide it. In the absence of state institutions providing adequate child care, and alongside the lack of adequate parental leave, the camera gained a privileged status—offloading the role of the state onto the vigilant (and potentially vigilante) mother who might always be watching. Meanwhile, in the developing fantasy life of the child, the camera forms a new link to imagined maternal care, locating in the lens an unseen mother who sees and hears everything.

The baby monitor and the nanny cam created, for the baby and for the nanny or other paid caregiver, an idea of a mother who could always be looking and/or listening. Teachers’ and daycare workers’ concerns about cameras in the classroom or crèche are regularly attacked as evidence that these care workers may have something to hide. Daycare workers raise legitimate concerns about cameras creating an anxious atmosphere in the classroom for teachers and children, being used for unannounced and unfair performance evaluations, and for spying by supervisors on private conversations between teachers unrelated to interactions with children. Workers also note that parents are at risk of reading as mistreatment or neglect of their child some of the normal waiting and frustration tolerance required of children in group care. A mother who tunes into a livestream of her toddler’s classroom as her child is crying and a worker is attending to another child may perceive bias or neglect in the treatment of her child, when what is happening in the classroom is in fact the difficult work of prioritizing multiple needs.

The nanny cam’s extension of the maternal gaze thereby begins to create new maternal functions. The purpose of the mother’s gaze is no longer principally to be sensitive towards or protective of her child. She watches and is felt to be watching as if supervising an employee, linking “good” maternal care with the role of a suspicious manager of those who work with children.

What the nanny cam and baby monitor were never before able to offer was a sense of when to look. The camera and the monitor pick up and transmit what they pick up and transmit. Some baby monitors have lights that signal the volume level of a baby’s sounds, but it is only with the recent introduction of AI to the realm of infant surveillance that there is an idea of a technology that can pre-process for the parent what is going on for the baby at the level of need. Here maternal sensitivity, or even the need to watch and wait in order to figure out what is going on, is replaced by the promise of an Artificial Intelligence that can tell a parent when his or her attention is needed. The mother who might be watching and reading what is happening is replaced by the omnipresent computer. New infant monitors like the CuboAi promise to alert parents when the baby’s face is covered, when the baby rolls over, and when the baby cries, tasks that used to involve attending, if not to the baby, then at least to what was being transmitted. It is not difficult to imagine that cameras in classrooms and nursery schools may soon promise to alert parents to signals of social strife or stress arising between young children and their teachers or peers.

Psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion once argued, contrary to the general thrust of psychoanalytic thought, that the principal therapeutic action in analytic work is to make the conscious unconscious. Analytic interventions in situations of severe disturbance help differentiate waking life from the dreamy sleep-walking that comes from a particular kind of damage, an inability of the mother and her world to contain and process the raw and overstimulating affects experienced by the developing infant in its earliest moments. Psychotic processes, Bion believed, are more common drivers of group life than any of us are generally comfortable acknowledging. Actions motivated by what he called “primary process thinking,” such as the need to lower anxiety by pairing, fighting with or fleeing from the other, and dependence on leaders or forces unrealistically endowed with special powers, motivate many of our actions in groups. While these forms of thought can be major drivers for creativity, they and other forms of psychotic process are also almost always in operation when a given social group cannot work. Looking at what is structurally similar to psychotic thought in our everyday experiences in new and “unsaturated” ways may help the most disturbed and disturbing aspects of every-day life move out of our everyday interactions with one another and into the more sustainable and less intrusive place of our dreams.

In a 1956 essay differentiating psychotic from non-psychotic forms of thought, Bion describes how projection might work within the psychotic system. He describes a patient who has a psychotic relationship to a gramophone. The patient, who has biologically intact sensory capacities and, physically speaking, can hear and see, has a delusion that he cannot hear, but that the gramophone can hear. The way of hearing that the patient projects onto the gramophone is distorted. There is a fantasy that something unwanted is being sent from the patient into the gramophone, and so the function returns to the patient in a persecutory way as what we might call “listening-in.” Should the delusion shift in terms of the projected function, so too might the sense of how one is being persecuted also change. Perhaps on another day the patient cannot see, but projects the function of sight into the gramophone. Now the function of sight returns in a persecutory way, and the gramophone is watching, spying or leering.

The infant-mother relationship is rife with anxiety, both parental anxieties about failing the baby and infantile anxieties about being obliterated by the absence of the other and the newness of the world. So what happens when we manage these anxieties by splitting off biological functions and projecting them into technologies? We may ask if there is a psychotic process that is active and two-fold in the use of surveillance technology in the infant-mother relationship. First a loss of a sense within the mother of an ability to perform a function—to hear, watch or read her baby, without the technology. And second, a persecutory return of the technology as harmful and overstimulating to the developing mind—listening in, snooping on, or manipulating observed emotions for perverse ends.

There are concrete benefits to AI technology being used in infant care. A medically vulnerable baby could, for example, be able to return home from the hospital and enjoy the predictability and rhythms of home life if a parent, usually a mother, can rest assured that should there be a sudden change in the child’s breathing, she will be alerted with enough time to save the baby’s life. But in the context of a capitalist economy, mass hysterical phenomena like the anxieties raised by the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and trial, and the anxieties about Satanic ritual abuse, end up driving the market for technological fixes far more than medical needs. In a situation where too much responsibility for protection and support is devolved from the state and society to the individual mother, technologies get marketed not as fixes for specific, rare concerns but to provide superhuman replacements for what have in the past been good-enough human capacities to hear, see, and read infants. The risk that AI-equipped nanny cams represents is the formation of a new kind of mother—one who does not feel that she can read her baby’s needs without the AI, and thus becomes not a mother who uses a technology, but a mother who actuates the commands of the computer. This may end up representing a loss for many of a function most of us came to learn well enough from our human mothers—the ability to sensitively and compassionately read and respond to one another.

■

Benjamin Fife is doing his best to notice when he is managing intense anxiety by pairing, fighting, fleeing, or idealizing Bernie Sanders.