Working Mother

The radical pamphleteer Susannah Wright does not fit neatly into the contemporary feminist imaginary. She is a woman these feminists would like to forget: a woman who understood her class allegiances and fought for the universalism of an objective, shared reality.

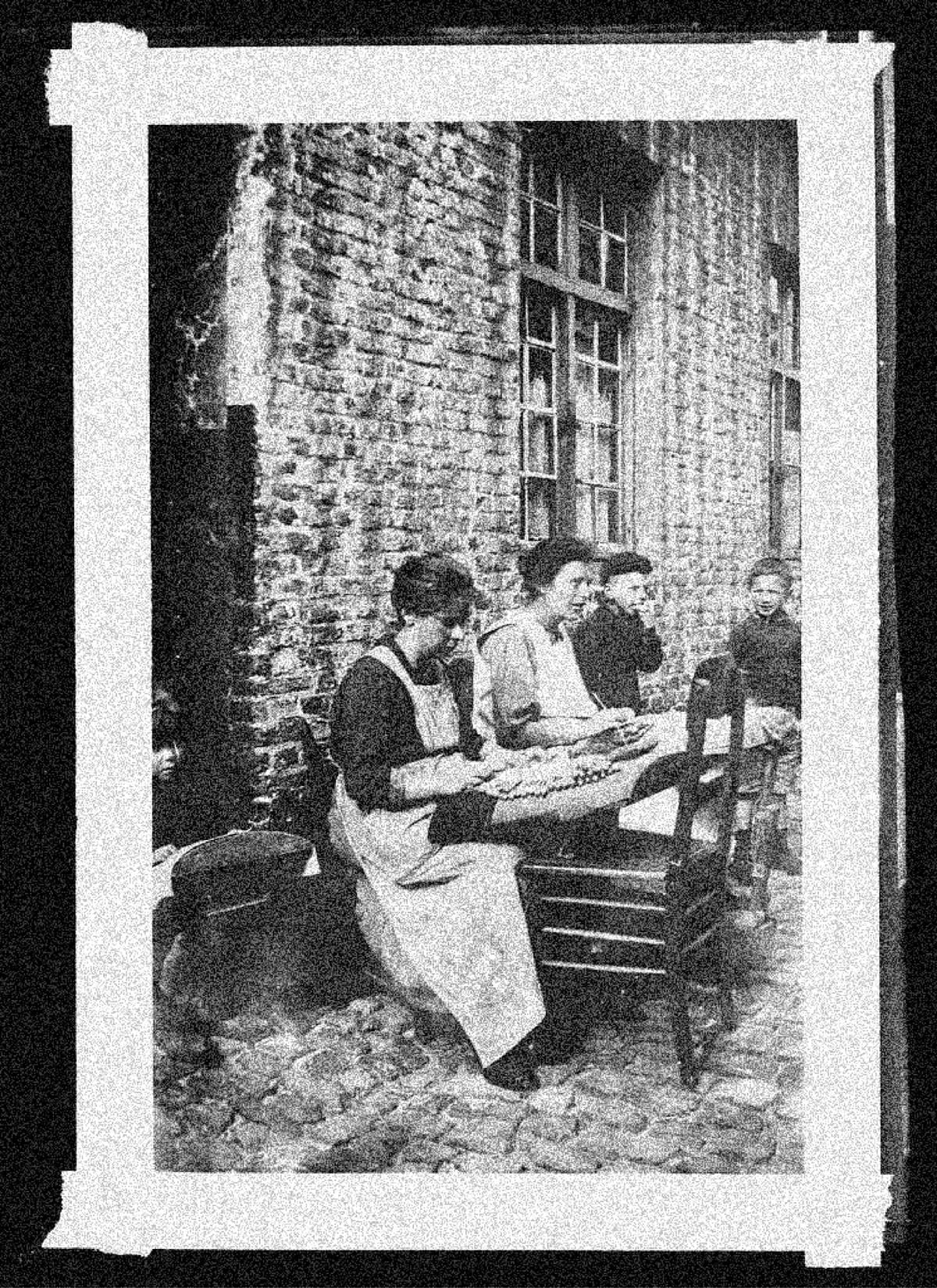

In 1822, at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, a radical Nottingham lacemaker named Susannah Wright appeared in court, acting as her own defense just after having given birth to a child. Wright was a nursing mother during her trial for “blasphemous libel.” She had been arrested for selling pamphlets defending universal (male) suffrage and freedom of speech. According to University of London Senate House librarian Tansey Barton, Wright “played an important role in providing access to books for the newly literate working classes; a very brave act when many were being sent to jail for either printing or publishing or distributing blasphemous and salacious books, and all during her pregnancy.”

At one point in her defense, Wright sought the court’s permission to retire to suckle “her infant child that was crying.” The crowd cheered her on, but the conservative press made her out to be a prostitute who had no womanly shame. She was already serving time in Newgate prison with her six month old when the court condemned her to another eighteen months of prison time. Newgate was one of the most notorious prisons in London: its squalor and pathos inspired prison reformers like Elizabeth Fry to demand separate quarters for women in order to prevent sexual violence against the female inmates. When Charles Dickens visited the prison in the early 1830s, he devoted an entire chapter of his first ever publication, Sketches by Boz, to a description of the pathos and poverty he saw there. In the women’s quarters, the inmates seemed to be “well provisioned,” but slept on mats on the floor in common rooms. It is likely that Wright slept in this way with her newborn during her trial.

If Wright had lived in our times, socially progressive people would certainly think of her as a “traumatized” person, whose private “trauma” and not her political convictions would form her political subjectivity. Derided by the bourgeois press as “wretched and shameless,” after being convicted of seditious libel, Wright remained fully committed to fighting for freedom and equality for the working classes. In prison, she must have survived circumstances of squalor, violence and deprivation, but after she was released from Cold Baths Prison in Clerkenwell where she served the rest of her sentence, she remained a staunch advocate for press freedom and equality and working class literacy.

Wright had been selling the pamphlets of free speech and universal suffrage advocate Robert Carlile. Carlile defied the authorities and questioned religious belief and the English monarchy, writing sentences that seem benign today, but were absolutely inflammatory two hundred years ago: “Kingcraft and Priestcraft I hold to be the bane of Society.” In his seditious and blasphemous pamphlets, he demanded the expansion of English democracy to include the working class. Wright appears at the end of E.P. Thompson’s study of the English working class to exemplify the general sense of working-class revolt and class consciousness that emerged in the early years of the Industrial Revolution. In her defense, Wright drew on the radical Enlightenment idea that all human beings have the ability to exercise reason, all while protesting the exploitation and de-skilling of artisans and craftspeople like herself. She raised her voice to defend her own right and the rights of the working class to read and publish ideas that questioned their subjugation. With increasing intensity after the Peterloo massacre of 1819, working-class militants protested against suffrage laws that restricted voting to property owners while the government acted to repress the free press in a country that was becoming more and more literate. Working-class readers called literacy “the steam engine of the moral world.”

Since Susannah Wright’s grievances were not gender based, today’s feminists would no doubt find her very disappointing. Indeed, the professional-class feminism of our times is built not on women’s strength, but their particular vulnerability and the specific accommodations that should be made for that vulnerability. Perhaps she should have been demanding a breastfeeding room.

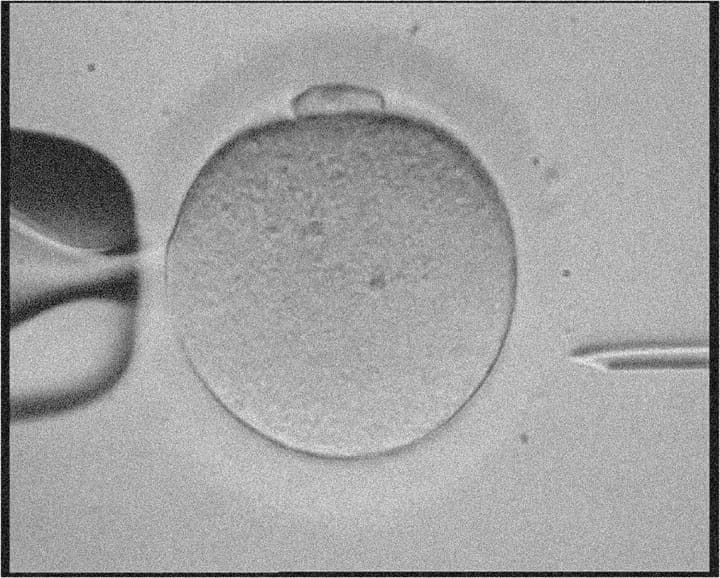

Instead, Wright attended to her infant in defiance of public mores governing propriety, while at the same time articulating her defense of universal male suffrage and working-class rights. In the courtroom, one might imagine mother and child engaged in a complex but intuitive process of adaptation on the mother’s part to the changing nature of infantile dependency. Wright was a perfect example, in this view, of D.W. Winnicott’s good enough mother. As a nursing mother, she could care for her child while also being temporarily absorbed in something other than her child’s needs. When the baby demanded to be fed, Wright asked for a pause in the proceedings and retreated into a private room in order to breastfeed.

In order for a child to survive and thrive, an adult human being, most often a mother, has to be both infinitely distractable and also capable of offering her entire self to the care of a vulnerable being. Wright was able, like most mothers, to lengthen the periods of inattentiveness administered intuitively and homeopathically to encourage the growing autonomy of the infant. Each of us who lives with the capacity for play and pleasure have experienced and overcome those breaks in maternal attention. Imperfect attention is critical to our psychic and physical development. In Winnicott’s theory of infant development, “holding” and being held are critical forms of intersubjectivity that allow the human infant to find its way into a world it can share with other human beings. Short but traumatic failures in a mother’s responsiveness allow a baby to begin to 1) discern an objective world and reality around them that is not them; 2) understand their own increasing competence in living in a world that surprises them; and 3) engage in a playful, pleasurable relationship to “transitional objects” that take on the intensity of the infant’s maternal attachment. This transitional space is the place of culture and sociality. It is in this space that human beings can enter safely and confidently into relationships of play and pleasure within a rich shared, objective reality.

Despite standing accused of extremely serious crimes, Susannah Wright, in the most ordinary and extraordinary of ways, knew how to defend herself from accusations of sedition while providing nourishment for a newborn. She served eighteen months of her sentence with her baby and when she was released, returned to lacemaking and continued her political activity by opening up a bookshop selling the works of Thomas Paine and Robert Carlisle. She is not listed as one of the famous prisoners of Newgate: they include Ben Jonson and Oscar Wilde, but her courage, unbroken spirit and desire for freedom were a discomfiting spectacle for the respectable, bourgeois members of her contemporary society.

Wright could not conceive of herself as a victim of anything but tyranny and exploitation: it was her understanding of her struggle in the context of a larger desire to overturn forms of political and economic oppression that gave her life, strength and achievements, as well as her suffering, deep social and political meaning. Her motherhood and prison sentence were burdens she bore lightly.

By the end of the twentieth century and in the first few decades of the twenty-first, Wright’s class-based political commitment would be construed by feminists as a sign of either naivete or moral and sexual depravity. In the contemporary feminist imagination, the social world is filled with bias and phobia, and universalism is the enemy of the individual who can only find justice in individual grievance. Susannah Wright is a woman these feminists would like to forget: a woman who understood her class allegiances and fought for the universal struggles for freedom that take place in an objective, shared reality.

The world that we inhabit together is built on the struggles of women like Wright, whose goal was the emancipation of all human beings from not only discrimination, but from the material conditions of exploitation that diminish everyone’s capacity for thinking, for loving, for playing and for working with others.

Excerpted from Traumatized (forthcoming Verso).

■

Catherine Liu is professor of Film and Media Studies at UC Irvine. She is the author of Virtue Hoarders: The Case Against the Professional Managerial Class and is at work on Traumatized (forthcoming Verso).