A Green New Trade Policy

Neoliberal free trade agreements in the 90’s dealt a crushing blow to the working class. The Left should learn the lessons of that period and support targeted tariffs paired with other industrial policies.

With Donald Trump soon to be in the White House, tariffs are now back in the news. There are several weeks until inauguration, but Trump has already been brandishing the threat of tariffs to everyone from geopolitical rivals like China to close neighbors like Canada and Mexico. Yet despite the current association of tariffs with Trump, the Left shouldn’t shy away from supporting strategic, targeted tariffs that can prevent a repeat of the harms of neoliberal globalization and build a green industrial sector.

Globalization and its Discontents

Contrary to the neoliberal consensus that globalization and free trade are a major boon to the world, both have been a disaster for the American working class. There’s abundant empirical research that demonstrates that American workers are the biggest losers of free trade with China. Stanford’s Center on China’s Economy and Institutions estimates that “the China shock” accounts for nearly 60% of all US manufacturing job losses from 2001 to 2019. The most affected demographics were white, less educated, older, and poorer, and increased Chinese imports helped swing these workers to the Right much as NAFTA did. Employers benefited from this arrangement, as they were happy to replace American workers with much cheaper Chinese labor. Further research shows that while Midwestern and Southern blue-collar workers were losing their jobs, college-educated workers on the coasts actually benefited from the China shock, further explaining the polarization of the pro-globalization PMC against the rightward-shifting proletariat.

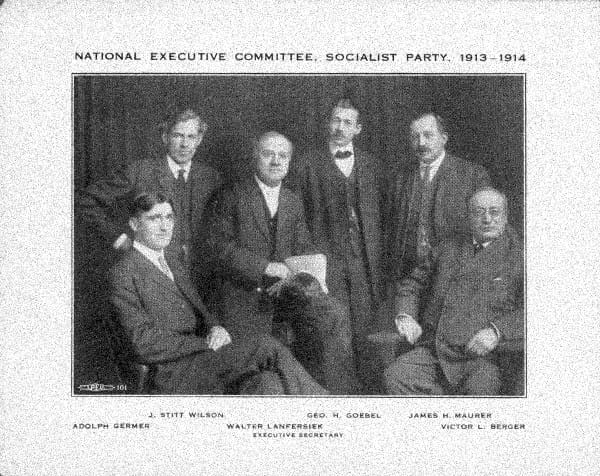

The political fight over free trade with China back in 2000 starkly demonstrated who the beneficiaries and losers were. As Ho-Fung Hung has shown, megacorporations like ExxonMobil, AT&T, and IBM were the most ardent supporters of free trade with China, while labor unions and Bernie Sanders stood in opposition. The latter lost, ushering in a wave of further deindustrialization that destroyed union manufacturing jobs. Free trade with China was a devastating defeat in the decades-long neoliberal war that American capitalists have waged against the working class.

In an admirable effort to avoid egging on a Cold War with China, leftists often apply a double standard: supporting free trade with China while opposing NAFTA. However, any honest accounting of globalization’s effects on the American working class must acknowledge that both of these policies were part of a neoliberal package that socialists should oppose. The right-wing populist backlash against globalization has roots in workers’ real material concerns over the damage wrought by free trade with China and NAFTA. If the Left wants to stop the Right, it’ll have to address those concerns seriously—and uncritical defenses of globalization don’t help.

Green industrialization should include tariffs

Defending trade protections has traditionally been standard fare for the Left. However, some leftists such as J.W. Mason have abandoned this position, instead arguing that tariffs have no business being on a green industrial agenda. Mason’s argument contains a strange contradiction. He starts off by favorably citing China’s infant industry promotion and correctly pointing out the US’s hypocritical criticisms of Chinese industrial policy. But he then immediately moves on to criticize one of the most important components of infant industry promotion: tariffs. Mason favorably cites Ha-Joon Chang’s Kicking Away the Ladder, but neglects to mention that the book is a passionate defense of tariffs. The second chapter demonstrates that tariffs played an essential role for development in all the high-income developed countries. Even countries that were relatively less protectionist—like Germany—still implemented tariffs on targeted key industrial sectors.

Mason claims that Chang’s argument is that developed countries and developing countries should have different economic strategies so tariffs aren’t supposed to be used by the former. But in doing so, he makes the serious error of conflating developed countries with developed industries. Infant industry protection is a strategy for upgrading underdeveloped industries, regardless of the income-level of the countries those industries are in. Developed countries usually don’t use infant industry protection because their industries are typically on the forefront of the technological frontier. But in the case of green technology, Western countries aren’t the leaders; China is. Relative to China, American and EU green manufacturing remains an infant industry, even if that infant is cradled in the arms of a developed country. Therefore, infant industry protections like tariffs that have been historically so successful can also benefit the development of an American green manufacturing sector.

Since China developed its industrial lead in green technology through infant industry protection, there’s no reason that the US shouldn’t try out the same policies—including tariffs. China’s electric vehicle (EV) industry grew behind a blanket 25% tariff on cars, the maximum allowed by WTO regulations. Tariffs played a prominent role in China’s current dominance in solar. When China put a 57% tariff on American polysilicon, an essential input for solar panels, it gave its nascent polysilicon producers crucial breathing room. A common sentiment is that the West should learn from China’s success. It is finally doing so—and part of the lesson is that tariffs are an important part of industrial development.

Both sides are whining about “cheating”

The US and EU have spent the last several years making misguided complaints about China “cheating” with its industrial policy. But international trade is not a game with clear rules, and both the US and EU have also subsidized their green industries. Yet Western commentators (who usually consume little to no Chinese media) fail to note that these accusations are symmetrical. Chinese state media outlets decry the “wrong practices” of the EU for putting up tariff barriers, despite the fact that China has used these tools themselves. Senior Chinese officials have made the same accusation of “unfairness” against investigations into China’s EV subsidies. The hysterics around “unfair” trade practices are at play in both China and the West. And this symmetry must be acknowledged to understand the political dynamics of trade policy on both sides.

Many commentators on the Left, who predominantly focus on the US and Europe, analyze Western policy towards China in isolation from China’s policies towards the West. The US and EU are portrayed as aggressors who have decided ex nihilo to pursue completely unprovoked anti-China policies. While this is true in many cases, this doesn’t apply here. As Kyle Chan notes in his excellent discussion of Chinese overcapacity, the protectionist backlash from the US and EU is partially a result of China’s own political errors:

China is not only explicitly trying to dominate critical industries, such as clean energy; it’s also bragging about it. This is part of a longer pattern of tin-ear geopolitics where China doesn’t seem to fully appreciate how much its cheerleading and boasting aimed at domestic audiences—like talking up ‘China’s manufacturing prowess’—is angering foreign audiences and fueling a powerful geopolitical backlash.

China employed protectionist measures for their green industrial policy, but now that the US and EU are doing the same, Chinese officials have been whining about cheating in the same fashion that the West has. Instead, China should take other countries’ concerns seriously and scale back its wolf warrior responses. As Chan writes, “Rather than simply pushing back more forcefully and asserting that its vision of the world is the right one, China needs to better appreciate the concerns of other countries and incorporate this into its policies.”

The current wave of US and EU protectionism is thus partially a result of China’s own unwillingness to find a cooperative solution that could accommodate other countries’ concerns about being left out of the green transition. The fact that these tariffs are not only about the brewing Cold War can be seen in the tensions between geopolitical friends caused by green industrial policy. After the unveiling of the IRA, EU leaders were furious, with French President Macron describing it as “super aggressive.” In Brazil, Lula brought back tariffs on Chinese EVs as a way of boosting the domestic auto industry. These responses aren’t weapons in a geopolitical war between the US and EU or between Brazil and China, but rather attempts to participate in developing emerging high-tech industries.

For the EU, being pushed out of green manufacturing sectors by China isn’t just a hypothetical. It’s already happened. In 2012, the European Commission announced an anti-dumping investigation into Chinese solar panels. In response, China began threatening to cut off imports of German luxury cars. The EU and China ended up avoiding further trade escalation as German Chancellor Angela Merkel successfully pressured Brussels to come to a negotiated settlement. While this was a clear-cut win for globalization, the ultimate result was the utter annihilation of the European solar panel manufacturing industry. Had the EU been more proactive in defending its solar industry, it could have retained high-skilled manufacturing jobs and contributed more to the green transition. This loss has certainly not been forgotten by the EU and its new tariffs on Chinese EVs are meant to prevent a repeat of this mistake.

Socialists should care about Chinese overcapacity

Some argue that the best-case scenario would be to accept the flood of green Chinese imports to accelerate the green transition as quickly as possible. But if socialists care at all about preserving the “New Deal” in the Green New Deal, they must reckon with the challenge of Chinese overcapacity. Some on the Left casually disregard fears of Chinese overcapacity. They rightly note that global demand for green tech can meet the massive supply being generated in China. But what matters here is not global overcapacity, but Chinese domestic overcapacity. Right now, China’s domestic market couldn’t possibly consume all of the green tech that China produces. Therefore, Chinese producers’ only option is to flood global markets with its much cheaper exports, wiping out foreign firms trying to gain a foothold in the industry.

The evidence for Chinese overcapacity is overwhelming. Western governments are certainly maliciously abusing overcapacity as a cudgel against China. Given the current hawkish consensus on China, Washington is using any avenue of criticism it can find. But the West’s bad faith doesn’t invalidate the obvious empirical reality of Chinese overcapacity. Anyone who doubts this should listen to the Chinese producers who are themselves sounding the alarm on overcapacity.

Being left out of the green transition has real material stakes for the American working class. As Chan notes, discussions of overcapacity never bother with low-value sectors because the low-skill, low-wage jobs that come with them are undesirable. Debates about overcapacity are centered around advanced green technology because what matters are good jobs in emerging advanced manufacturing sectors. China’s overcapacity could easily lead to a second China shock that closely resembles the first, when American manufacturing was devastated, areas most impacted by Chinese imports saw millions of job losses, and workers swung to the right.

Concerns about Chinese overcapacity are not merely downstream from (real) geopolitical attempts to strangle China. The protectionist turn against China is global and happening across geopolitical camps in both the North and the South. Despite the BRICS’ portrayal of themselves as a bloc against US hegemony, most of its members have levied some kind of Chinese-specific protectionist measures. Even Iran, a member of Bush’s “axis of evil,” has tariffs on Chinese manufacturing goods. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, as emerging economies are amongst the most vulnerable to China’s overcapacity.

To prevent a second China shock and revitalize the labor movement, socialists should commit themselves to supporting a green industrial policy that includes tariff protections from specific Chinese imports. For example, no American automaker right now could compete with China’s impressively cheap and high-quality EVs. If the US simply opened the floodgates, American EV makers would be wiped out. In this scenario, an American transition from combustion engine cars to EVs would destroy the US’s auto industry and along with it one of America’s last remaining powerful labor unions. Supporters of green capitalism unconcerned about union auto workers can scoff off these concerns, but socialists who care about revitalizing the labor movement cannot do the same.

In addition to expanding unionization, reindustrializing the US with green industrial policy should be a crucial goal of the Left. Deindustrialization has wrought all sorts of social damage to workers. It’s no coincidence that Trump’s successful 2016 campaign vigorously attacked Clinton for the deindustrialization wrought by NAFTA. Outside the global North, premature deindustrialization has halted the progress of the developing world and mired it in poverty. For the sake of workers, stopping the ascendance of the far Right, and the overall health of American society, socialists should support some degree of reindustrialization—and the green transition represents our best opportunity to do so.

The Path Forward

None of this is to say that free trade is inherently bad and that tariffs are always good. As a general rule of thumb, socialists should oppose broad tariffs because they are merely a handout to domestic capitalists. Trump’s across-the-board tariffs didn’t provide many benefits to the working class or help spur American industrial development.

While deeply flawed, Biden’s tariffs represent an improvement upon those of Trump. They are far more targeted and designed to protect America’s growing industries in green technology. The subsidies of the IRA and Biden’s tariffs are a welcome shift to the kinds of industrial policy that China itself used to reach its dominance in green technology. In the case of battery production, the IRA has already made major strides, with planned cell capacity doubling in just a year’s time. Used strategically, targeted tariffs can help spur on this wave of domestic green investment.

However, tariffs alone are insufficient to promote the development of a domestic green manufacturing sector and could even harm it. Tariffs sometimes protect inefficient domestic producers from foreign competition and prevent them from increasing productivity. The US’s tariffs on Chinese solar panels in 2012 backfired spectacularly. China avoided this by combining protectionist tariffs that defended from external foreign competition with a brutally competitive internal domestic environment. Many Chinese EV producers duked it out in the market and survivors like BYD emerged as hyperefficient champions. Tariffs cannot simply be a giveaway for domestic capitalists. They need to be paired with a strategy that ensures that domestic firms are increasing their productivity and concrete sunset clauses so that their tariff protections are only temporary.

Biden’s EV tariffs, however, lack this strategic component. The tariffs on EVs were set at a whopping 100%, effectively blocking the possibility of any Chinese EV imports. To avoid the risk of coddling domestic automakers, Biden’s EV tariffs should have been better calibrated to level the playing field with Chinese competitors rather than completely locking them out. Like the US, the EU also recently raised tariffs on Chinese EVs. But while the US tariffs were designed to make Chinese EV imports impossibly expensive, the EU’s tariffs were far milder and firm-specific following a subsidy investigation that invited cooperation from auto firms in China. As one China-based former Chrysler executive put it, the EU tariffs were a speeding ticket while the Biden tariffs were a stop sign with a moat full of sharks. Instead of completely blocking all Chinese competition, the EU’s tariffs were calibrated to give European producers some breathing room while still maintaining Chinese competitive pressure.

Biden’s tariffs were narrowly focused on keeping Chinese competition out. But the larger benefit of tariffs is that they can bring foreign investment and technology in. When countries put up tariffs, foreign manufacturers can jump over these tariffs by setting up factories and directly producing in the walled-off economy. By manufacturing in the same country as their target market, foreign producers get direct access to their consumer base without having to pay hefty tariffs. In this scenario, countries use access to their domestic consumer markets as a bargaining chip to receive foreign investment, learn new technologies, and create domestic jobs. Unsurprisingly, this kind of strategy has been successfully used by China for decades.

Looking across the Atlantic, we can see how EU countries have been employing this strategy with some success. The EU’s anti-subsidy investigation that led to tariffs on Chinese cars actually made Chinese producers more interested in moving production to Europe, with 64% of survey respondents saying that the investigation had a positive impact on plans to build factories in the EU. In anticipation of new EU tariffs on EVs from China, Volvo announced that it would be moving production of its EX30 and EX90 models from China to Belgium. Since the EU is a key market for Chinese EVs, Chinese-owned car makers like Volvo are incentivized to set up production in the EU to get around tariffs. This creates manufacturing jobs in the EU and sets up opportunities for technology transfer so that European companies can learn from Chinese EV producers. Outside the EU, both Turkey and Brazil have successfully leveraged tariffs to bring in new EV factories from BYD.

The US is in an even better position to implement such a strategy. For Chinese producers who are locked out of the American market by tariffs, their best way around protectionist walls is to directly produce within the US. The US, with the largest domestic consumer market in the world, has more bargaining power than any other country and is a vast ocean of demand that would be irresistible for Chinese producers. The EV price wars in China have made profit margins on domestic sales razor-thin and firms are looking to foreign markets to shore up their financials. Even a small slice of the American market would be a major boon for Chinese firms.

Thus, the US should give Chinese green tech manufacturers a route to bypass tariffs if they agree to create joint ventures with US firms, share technological know-how, set up factories in the US, and hire American workers. This could be a win-win that would hasten America’s green transition, create (potentially union) manufacturing jobs, and give China access to American consumers. Greater collaboration through Chinese green investment in the US can also further spur innovation in decarbonizing technologies. The impressive efficiency of today’s solar industry was in-fact an international process of technological development, with major contributions from the US, Japan, Australia, Germany, and China. In addition, increased Chinese investment into the US could help cool US-China tensions, as improving economic ties helps mitigate the chance of war.

Right now, this kind of US-China cooperation is highly discouraged by the IRA. The IRA’s Foreign Entities of Concern rule bars companies with 25% Chinese ownership from receiving IRA subsidies, making any Chinese green investment into the US unlikely. One of the few bright spots of American-Chinese industrial collaboration, Ford’s joint venture with Chinese battery maker CATL, has received intense pushback from Republican lawmakers.

Thus, hawkish geopolitics is currently the biggest barrier to smart trade and industrial policy. The American state is now dead set on strangling Chinese technological progress to the greatest extent possible. Helping Chinese green tech firms by giving them access to the American market is seen as an unacceptable price to pay, even if it’s a boon for American manufacturing. For the sake of green industrialization, decarbonization, and reducing US-China tensions, the Left should support bringing Chinese green tech investment into the US.

Finally, any left vision for green industrial policy will have to be in line with socialist values and political objectives. The modern histories of China, South Korea, and Taiwan all show that robust industrial policy is completely compatible with right-wing authoritarian governments. In all of these cases, the primary purpose of industrial policy was building national strength and economic development, not egalitarianism. For socialists, green industrialization should not be seen as an end in-and-of-itself, but rather as an opportunity to rebuild workers’ power and to fund social democratic policies. Subsidies and foreign investment are good for American society if they mean worker unionization, high wages, and good labor conditions. Economic growth and profits from green investment could be taxed to fund crucial social democratic policies like Medicare For All.

With the upcoming Trump administration, it’s highly unlikely that any of this is on the table. But to win back workers, the Left can’t be nostalgic for the very free trade policies that lost them. Socialists should support limits to free trade when it poses a threat to the working class, and support economic cooperation where it’s beneficial. Doing so could provide the context to rebuild a base of worker support necessary for a serious Green New Deal.

■

Daniel Cheng is a former Sociology PhD student and independent researcher on Chinese political economy.