The Right to Make Promises

The editorial introduction for Damage Issue #4, “Responsibility”

Our fourth print issue, on the theme of "Responsibility," is currently at the printer and will be shipping out soon. To make sure you get your copy, become a paid subscriber of Damage today! What follows is the editorial introduction to the issue.

There is a modern creation myth out there, found in scattered works of Nietzsche and Freud, that goes something like this: there once was a group of nasty, ambivalent creatures who, finding themselves bound by the constraints of society, began to make themselves miserable in denial of their own nastiness and ambivalence. They became prone to hazardous flights of fancy in the hopes of recovering something that was never there to begin with. They festered; they stewed. It’s mostly a revolting story about the development of morality and religion and other contradictory artifices.

But there’s a light at the end of the tunnel—the possibility of overcoming our moral baggage and embracing what Nietzsche calls “the ripe fruit” of this whole sordid development:

the man who has his own independent, protracted will and the right to make promises…. he is bound to reserve a kick for the feeble windbags who promise without the right to do so, and a rod for the liar who breaks his word even at the moment he utters it [out of a] proud awareness of the extraordinary privilege of responsibility….

For Nietzsche, as for Freud, an enjoyment of this privilege of responsibility would entail an overcoming of silly, moralistic denunciations of self and other, as well as a sublimation of our drives into freely chosen forms of obligation. It’s a legitimate good of modernity that we’re encountering here, and it’s a shame, as Taylor Hines writes in “Fool Me Twice,” that some today wish to renounce it.

Nietzsche and Freud both would have been astounded by the degree to which we have been “liberated from morality of custom” but without any corresponding sublimation, left untethered to anything but the vagaries of the market. At the macro level, as Anton Jäger contends in “The Crisis of Coercion,” this trajectory has left states without the defining capacity for public control. At the micro level, it’s resulted in an embarrassing neglect of basic municipal responsibilities, as Amber A’Lee Frost details in “Potholes” through the lens of the Worcester City Council.

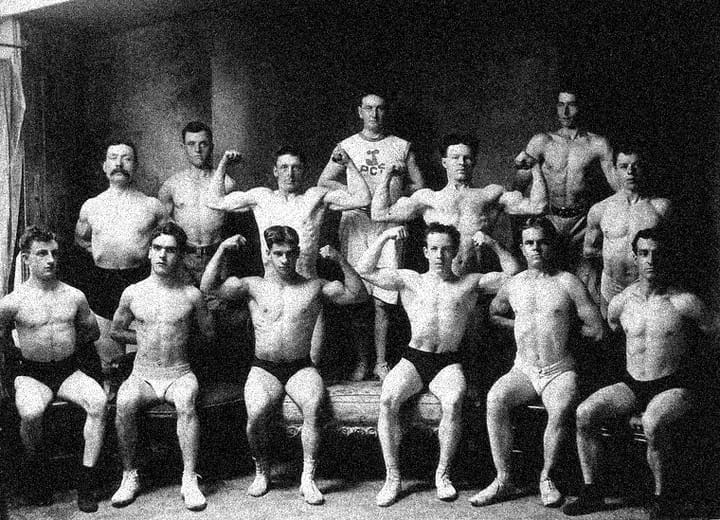

While it is not necessarily the most consequential manifestation of contemporary irresponsibility, social media certainly represents it quite well. At some point we are going to have to choose whether it is a platform of free expression or a vapid excrescence of a wrong society; that only conservatives really hint at the latter is not a great sign. In “Self-Catfishing on Steroids,” Jason Myles analyzes the radical form of young male alienation on display in the use of steroids for quick gains and quick fame on social media platforms. Daniel Boguslaw finds some promise in the new media forms in “Breaking News,” but only if the journalists using it take inspiration from an older generation by ignoring the trappings of partisan praise and attacking the powers that be.

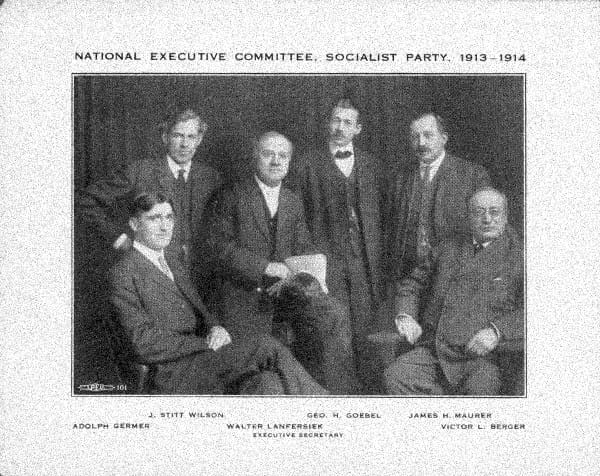

Damage is particularly concerned with irresponsibility on the political Left, and a number of articles here are focused on left-wing excesses and failures. In “Ending the Spectacle of Infantilism,” Catherine Liu chides a self-satisfied left-liberalism that encourages infantile displays of emotional expression in place of mature political engagement. Dustin Guastella focuses much more squarely on the inadequacies of the Left in “It’s Our Fault,” arguing that the current class composition of the Left has led it to support a spate of misguided and unpopular ideas—ideas that are components of a general orientation that the Left must definitively renounce if it is to be responsible and successful today. In “The Responsible Socialism of Adolph Germer,” I offer up the story of one socialist who came to see responsibility as a core left-wing value: Adolph Germer, the first organizer hired by the Committee for Industrial Organization.

The contemporary Left’s irresponsibility also manifests itself at the level of policy. In “Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Grid?,” Matt Huber and Fred Stafford argue that left-liberal visions of rooftop solar and 100% renewables work counter to what must be the goal of creating and maintaining a reliable, balanced electrical grid. Finally, Chantal Forrest works through the maze of the policing and incarceration debate on the Left in “Public Safety is a Social Good, and Simple Binaries Aren’t Helping Us Achieve It,” arguing that the Left must not cede the issue of public safety to the Right.

Much like Germer and other CIO organizers, the civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin also emphasized the importance of political responsibility, and how it was being abdicated in the mid-1960s for what he called “frustration politics.” Sadly, his portrayals then still ring true today.

A social movement, if its imprint is to be permanent and transforming, must have an economic base. Moral fervor cannot maintain it, nor can the act of participation itself. There must be a genuine commitment to the advancement of poor and working people. To have such a commitment is also to have a militant sense of responsibility, a recognition that actions have consequences which have very real effects on the individual lives of those whom one seeks to advance. Far too many current movements lack both an economic perspective and a sense of responsibility, and they fail because of it.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong writes about labor & logistics at On the Seams.