Liberals and the Left tend to ignore the importance of a reliable electricity system, pushing visions of rooftop solar and 100% renewables out of line with the reality of our electrical grid. A responsible politics must aim to deliver what a reindustrializing society depends on: a stable grid.

In 2000, the National Academy of Engineering deemed the modern electricity grid the greatest engineering achievement of the twentieth century—greater than air travel, computers, and health technologies (also included in the top twenty). The marvel of electricity is that it is a fundamentally social infrastructure: everyone connected to the grid relies on a vast planning apparatus to ensure the level of electricity generation (supply) is always exactly equal to the amount of demand and fluctuates within very tight limits. If not, the entire system could fail, requiring a “black start”, which can take months, if not years, to repair.

Keeping this system in balance is thus an urgent social responsibility. For most of the history of electrification in the United States, that responsibility was largely shouldered by publicly regulated electric utilities. Yet, as we explained in a previous issue, this changed in the 1970s when neoliberal reformers decided utilities were too monopolistic and uncompetitive to address the energy challenges heading toward the new millennium. The result was what some call deregulation, but the key term here is “unbundling.” No longer would a single entity harness central planning and a socialized investment model to run the system holistically. The grid was rather broken up into separate markets with hopes that the forces of competition would improve technology and lower prices for consumers (the record on the former is positive; the latter not so much).

In 2025, however, the grid appears as fragile as ever, with blackouts increasing, and it’s not entirely clear where the responsibility lies in keeping the whole system in balance. Grid governance is described as “byzantine”, with an overlapping set of mostly private institutions separately charged with aspects of grid reliability, including Regional Transmission Organizations, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, and utilities themselves.

The most recent catastrophic failure in recent memory was 2021’s Winter Storm Uri in Texas: millions lost electricity for days and 246 people lost their lives. In the fallout, a court actually ruled that independent power producers—largely owners of natural gas-fueled power plants—actually have no responsibility to keep the lights on for customers. The lawyer representing these “merchant generators” explained that this was in fact a policy choice: “because of the unbundling and the separation, you also don’t have the same duties and obligations [to consumers].” Indeed, because of the extreme deregulation of Texas’s electricity grid, it is a legal statute that the generation and retail sides of electricity must be run in isolation from each other in the name of market competition. The generators of electricity need only be responsible to their shareholders.

In lieu of any public commitment to grid reliability, individual households are losing trust in the grid and turning to diesel-powered generators. One of the leading sellers of such generators, Generac, reports annual net sales have risen 285% from $1.4 billion in 2013 to over $4 billion in 2023, with roughly half of these sales going to residential customers. Households increasingly see electricity as their own individual responsibility to prepare for the inevitability of blackouts.

In an appropriately titled article, “What’s Good For Generac Is Bad For America”, the energy analyst Robert Bryce explains that individualizing responsibility for reliability is not available to everyone: “... [Generac’s] target demographic is buyers whose homes are worth $500,000 and have household incomes of $135,000 or more per year.”

Complicating all of this, of course, is climate change, which may make some of the storms straining grid reliability worse. Conservatives might shrug away the responsibility to transition to clean energy in response, but liberals and the Left also tend to ignore the importance of a reliable electricity system, sometimes as a misguided reaction to the Right’s hostility to curbing carbon emissions. The New York Times even claimed efforts to “address the reliability and resilience of the electricity grid” were “top concerns for climate change deniers.” And the New School’s Genevieve Guenther, author of The Language of Climate Politics, ranks “resilience” as one of six words that animate climate denial. (Another is “growth.”)

For the affluent consumer who’s concerned with climate change but not with grid reliability, one consumer product promises an enticing solution: the individual responsibility of a Generac generator but without the carbon emissions of its fossil fuel combustion. Or at least that's the promise on which they’re sold.

Rooftop Solar Against the Grid

In 2015 Tesla announced its “Powerwall” battery system, and at the launch event CEO Elon Musk floated an enticing prospect: “... you can actually go—if you want—completely off-grid, you can take your solar panels, charge your battery-packs, and that’s all…you use…” His caveat “if you want” suggests he himself was not entirely sure of the viability of this off-grid proposition. The typical household simply needs more power than what can be provided by the sun’s daylight spread across nighttime hours with short-term batteries. Indeed, early reviews of the Powerwall said they didn’t even work well with solar panels and required a grid connection for an adequate charge.

Nevertheless, the dream of going “off-grid” and privatizing responsibility for electricity production via abundant sunshine is a powerful one across the political spectrum. One such fierce advocate of rooftop solar, Debbie Dooley, is a founder of the Atlanta Tea Party chapter. Dooley complains of the “centralized” power of her utility Georgia Power and the grid’s vulnerability to terrorist attack. For her, rooftop solar is a way for ordinary households to participate in the electricity market: “The average person cannot build a power plant, but they can install solar panels on their rooftop, and they should be able to sell that energy to friends and neighbors if they wish.”

Climate liberals of different political persuasions tend to envision rooftop solar and personal battery systems as a form of individual responsibility to take part in the transition away from fossil fuels. In an article in The Atlantic, prominent climate researcher and political scientist Leah Stokes boasted that the consumer incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) helped her “break up” with fossil fuels: “From the beginning, I knew I wanted to cover my roof in solar panels. That way, I could generate clean energy for my house and car.” In other political commentary, Stokes’s rationale for societal adoption of rooftop solar doesn’t sound much different than the Tea Party one: “In the vast majority of places you don’t get to choose who is supplying your electricity. And so if you decide to put solar on your roof, you begin to undermine that monopoly status.”

In the early twentieth century, progressive proponents of classifying electricity as a “public utility” believed its status as an essential network service made it a “natural monopoly,” but today the Right and the Left seem to agree that it would be preferable to allow a more dispersed set of consumers and price signals to shape our electricity system. It is this policy consensus that undermines the social responsibility for the grid as a whole.

There is another major problem with this libertarian vision of green privatism: electricity experts agree rooftop solar is a more costly and inefficient way to deploy solar energy on a societal scale. With redundant electrical infrastructure across rooftops and layers of competing administrative costs, it’s simply cheaper and more efficient for the grid to have relatively fewer utility-scale solar farms.

Rooftop solar’s economic viability, for the owner of the roof, therefore depends on how such uneconomical power is compensated. Both the homeowner and the solar installation company require a guaranteed revenue stream for the power produced, in addition to the tax credits provided by the IRA and various state-level incentives. The solution is a policy now adopted in almost every state: net energy metering (NEM). In her book Short Circuiting Policy, Stokes calls NEM “crucial” for the growth of solar energy and makes NEM sound perfectly fair: “Typically [NEM] policies pay customers the same price that it costs them to purchase electricity.” Other analysts have described NEM policies as the “bedrock of solar PV incentives.”

Any viable energy policy to confront the ecological costs of climate change must also address the substantial costs to maintain the reliability of the system as a whole.

Though the power generated by each tiny rooftop helps offset power that otherwise comes from a power plant, the shared electrical infrastructure to enable it comes with a cost. For example, local distribution feeders must be upgraded to handle increased two-way power flow, rather than the traditional one-way flow from power plants to homes, and myriad new components and software systems must be installed to handle any dangerous fluctuations from people’s systems. At utilities across the country, for the past decade, all of this is paid for in the utility bills of the entire consumer base. Though in certain cases these upgrades and customer-owned resources can help the utility do its job more effectively, political demands for universal “solar access” undermine the capacity to plan for targeted upgrades that optimize the whole system.

Worse still, under NEM policies, for every bit of self-produced electricity that a rooftop solar owner doesn’t purchase from a utility, that’s a dollar not spent on maintaining and upgrading all common utility infrastructure. In other words, rooftop solar owners compensated with NEM are skimping on the public bill even though the support for their individualism adds to it. Moreover, if it’s a particularly sunny day, the utility or balancing authority doesn’t necessarily need all that solar power all at once; whatever cannot be exported to a neighboring region with fewer solar producers is then “curtailed,” or wasted.

Severin Borenstein, a professor at Berkeley’s Energy Institute at Haas, has spent years arguing the case against NEM in California, a state with skyrocketing and unaffordable electricity prices for the working class. “When a customer installs solar” and is compensated with NEM, Borenstein wrote in 2021, “their share of the fixed costs are shifted to other ratepayers who are poorer on average. Net Energy Metering hurts the poor. It’s that simple.” This is also the case against NEM policies made by many utilities too.

On the question of cost-shifting, solar industry proponents and liberal climate advocates tend to shift the conversation to the costs of fossil fuels and climate change. In the case of Arizona, Stokes argues that investor-owned utility Arizona Public Service “was imposing costs on the public through air pollution and climate change, in its failure to transition away from fossil fuels.” This is a legitimate point, but it is a misdirection from the core of the question of why solar owners should be relieved of the social responsibility for grid infrastructure. Any viable energy policy to confront the ecological costs of climate change must also address the substantial costs to maintain the reliability of the system as a whole.

It would be one thing if the rooftop solar industry was run with a public mission in conjunction with the public utility system more broadly. Startup company Sparkfund argues this is the best path to maximizing distributed energy resources’ potential at the scale required. But as a recent exposé in Time Magazine illustrates, the rooftop solar industry is beset by accusations of fraud and predation that traps homeowners in unaffordable lease payments and debt—all while selling solar loans as securities to Wall Street. It’s also an industry that is almost entirely nonunion, which is one reason why unions also prefer utility-scale projects to small-scale rooftop ones as the more reliable path for good, dignified, stable careers in the solar industry.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk, whose Powerwall promised off-grid living, has used his new government role in the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to cut off funding to USAID workers in his home country of South Africa. The funding paid for their grid electricity, and now they are trying to rely on solar panels and batteries. Unfortunately for them, it's not enough to power their AC, stove, laundry, or security system, and when it rains they risk losing power entirely.

100% Irresponsible

If rooftop solar individualizes responsibility for a reliable electricity service by purporting to exit the grid, one mantra held up by progressives, climate activists, and socialists alike abdicates it entirely: “100% renewable.”

“What Medicare for All is to the healthcare debate, or Fight for $15 is to the battle against inequality, 100% Renewable is to the struggle for the planet’s future,” wrote prominent environmentalist Bill McKibben in a 2017 cover story for In These Times. Rather than mere forces of production, an exclusive and absolute deployment of, and dependency on, renewable energy technologies has been elevated to a core political priority on par with Medicare for All.

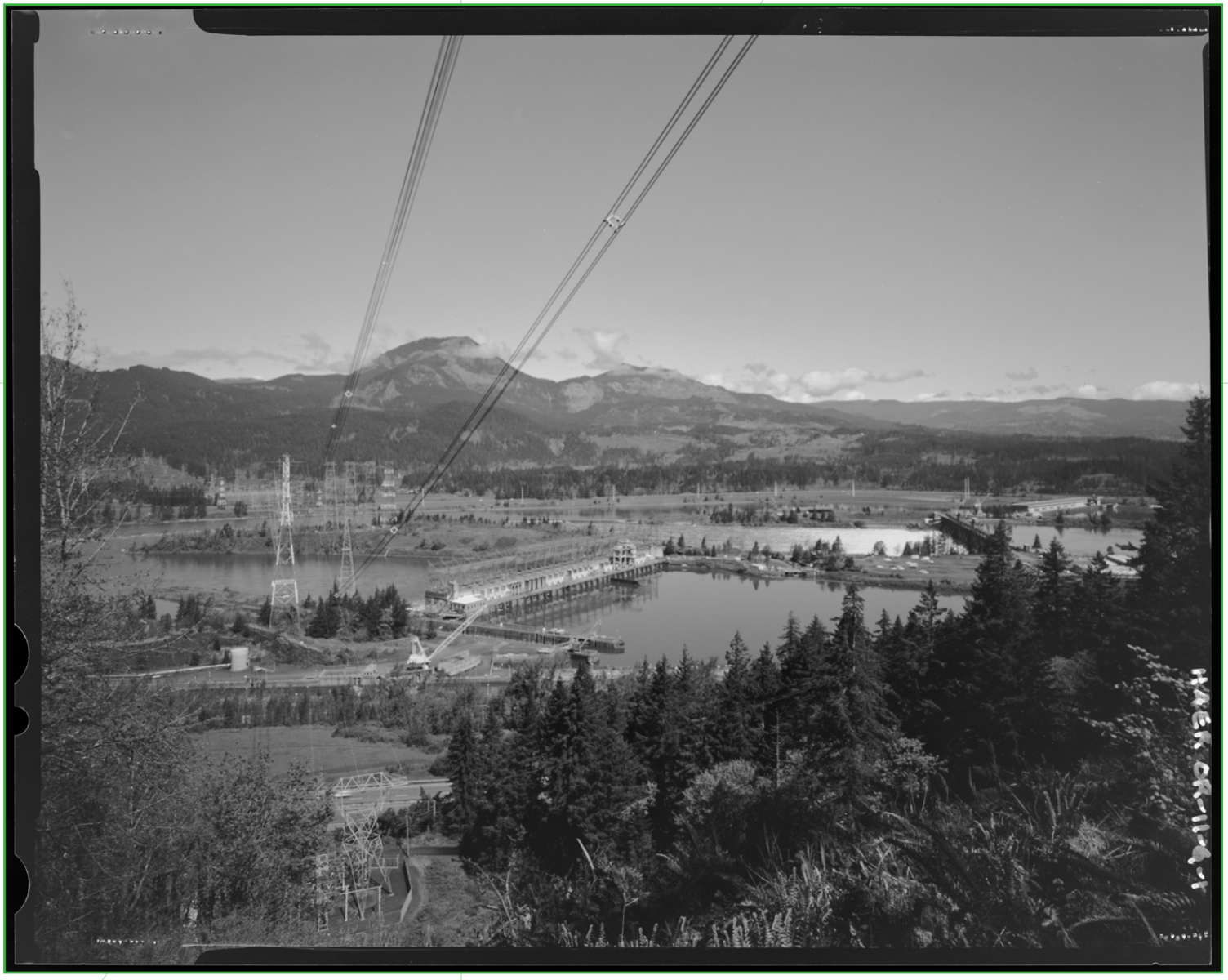

Would a 100% renewable electricity system even make sense? The naive, cliched explanation for what makes that prospect so dubious still holds true: the sun doesn’t always shine, and the wind doesn’t always blow. A 100% renewable-powered system exists in activists’ and academics’ heads but not anywhere on earth, at least not at the scale of an industrial society. Those places that come close are predicated on the limited geographic blessings of large hydroelectric capacity and are generally still interconnected into a larger, less renewable grid with neighboring territories. Meanwhile, in the real world, the institutions and experts concerned with grid reliability continue to assert the necessity of “dispatchable” or “firm” generation when weather does not cooperate.

Rooftop solar owners compensated with net energy metering are skimping on the public bill even though the support for their individualism adds to it.

Luckily for activists like McKibben, a cottage industry of academics armed with oversimplified models publish countless studies purporting to justify the engineering possibility of 100% renewable systems (“100% wind, water, and solar” in particular). One such academic is Stanford professor Mark Z. Jacobson, who infamously resorted to defamation lawsuits when his work eventually came under scientific scrutiny. Outside his corner of academia, away from sympathetic activists and journalists, he's more punchline than prophet. But over the past decade McKibben has repeatedly cited Jacobson’s work—and often his star-studded nonprofit The Solutions Project—to justify the 100% renewables gospel as a progressive demand in the pages of In These Times, The Nation, The New Republic, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, and Rolling Stone. For his New Yorker column last summer, he went as far as to uplift Jacobson's solar-powered home (“at the end of a classic suburban cul-de-sac on the edge of the campus of Stanford University”) as his prime example of the viability of 100% renewables. He even got his friend and fellow Vermonter Bernie Sanders to co-author a 2017 Guardian op-ed with Jacobson making the case for it.

Despite their confidence in it, proponents of 100% renewables usually don’t realize how the term obfuscates the reality of the grid. A consumer of electricity—like a company, or all the utility customers in a state—is said to be some percentage “renewable” based on the proportion of their annual electricity usage that is backed up by purchases of renewable energy certificates, or RECs. Consume all the electricity you want when it’s not sunny, then purchase RECs from a solar developer at different times, when it is sunny, and at the end of the year your electricity consumption can be claimed as renewable. Notoriously opinionated soap brand Dr. Bronner’s, for example, proudly cites McKibben on their boast of 100% renewable operations—substantiated via REC purchases. (“I’m convinced that if every home had solar panels on the roof, we could create all the energy we need without exploiting the surface of the Earth,” Dr. Bronner foretold in 1986.)

Or take the example of Georgetown, Texas, a red town in a red state that very publicly went 100% renewable in 2017. That, too, was just about financial contracts: at the same time that they contracted for enough solar and wind RECs to cover their annual electricity usage, they also contracted for the power produced by a nearby gas plant. Bernie Sanders even invited their mayor onto his 2018 climate change panel as a hype man for green markets. But in 2019 their green market mechanics finally backfired: the city began selling the RECs to others for more cash flow and had to stop claiming 100% renewable status. Unscrupulous academics and climate NGOs continue to cite a list of five purportedly 100% renewable cities that includes Georgetown—like a 2022 report on “community utilities” from the Democracy Collaborative and the Climate and Community Institute, or “Democratizing Public Services” by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung—in order to justify the feasibility of their exclusive focus on renewables. In a way, our heavily financialized electricity system enables our intellectuals to avoid responsibility for understanding how their chosen political projects actually work.

It can’t be overstated the extent to which climate policy has been equated simply with the progressive march upwards of the percentage of renewables based on REC purchases and not grid reality. A majority of US states have now legislated a “Renewable Portfolio Standard,” or RPS, which aims to reach a target percentage of renewables based on these fictions.

The decarbonization of the electricity system—and especially of the broader economy—will of course require renewable energy technologies to some degree. But it will also require other emissions-free technologies that serve the grid continuously, like nuclear power. The grid operator for New York State in charge of electric reliability, NYISO, has warned since 2022 that with the retirement of fossil-fueled generators and “[w]ith high penetration of renewable intermittent resources, dispatchable emissions-free resources will be needed beyond 2030 to balance intermittent supply with demand.“ In other words, wind and solar won’t cut it.

But 100% renewable doesn’t just forestall such clean technologies needed for decarbonization; it forestalls further fossil fuel combustion needed for keeping the lights on too. That’s especially challenging as populations grow, as power-hungry manufacturing comes back to America driven by Biden’s CHIPS and IRA laws, and as more heating, vehicles, and industrial processes are electrified as part of decarbonization policies.

What’s the Public Interest in Public Power?

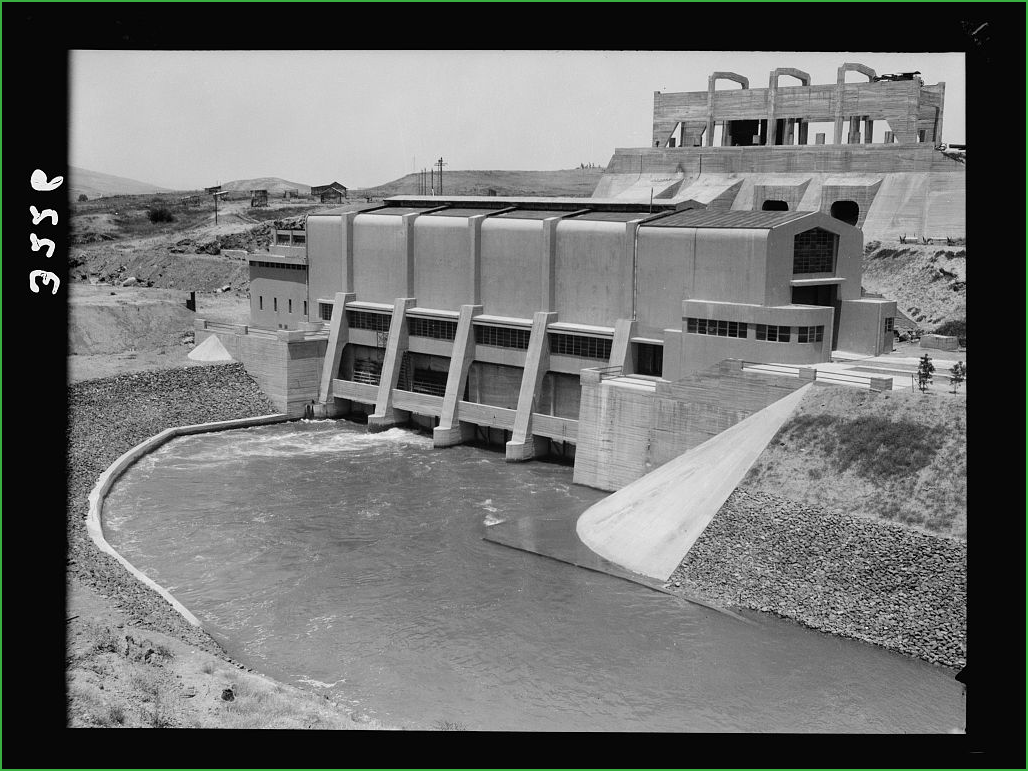

New York City faces electricity shortfalls starting in 2033, according to NYISO’s official assessment from last November, driven by increased demand and by the legislated retirement of the state-owned New York Power Authority’s gas-powered “peaker plants.” The fleet of seven peaker plants were whipped together and deployed within one year’s time back in 2000 when a similar shortfall for the city was projected for the following year—for emergency public need, not for profit.

Though NYPA’s peakers remain the cleanest, least-polluting power plants in New York City, they’ve nonetheless come under fire as “racist” “super-polluters” by Public Power NY, the coalition of Democratic Socialists of America and environmental justice nonprofits, several of whom fought the peakers back in 2000. The coalition’s laudable and successful campaign to revitalize NYPA resulted in 2023 legislation that gave it new authority to build and sell power from renewable projects—emphasis on “renewable”—to complement its fossil-fueled plants and its legacy hydroelectric dams. But it also mandated a 2030 retirement for those peaker plants that NYISO is concerned about losing. The coalition's original bill had failed, but the administration of New York Governor Kathy Hochul rewrote it into the resulting law. It retained the public power essence of the original, moved the peaker retirement back from 2025, and scrapped the original’s absurd “100% renewable” public ownership requirement, among other improvements.

In a way, our heavily financialized electricity system enables our intellectuals to avoid responsibility for understanding how their chosen political projects actually work.

Meanwhile, Public Power NY seems fixated on New York’s own RPS target of reaching 70% renewables by 2030, rather than the more general target of 100% emissions-free electricity by 2040, with little concern for NYPA’s responsibility to the grid as a whole. That’s for someone else to worry about, like NYISO and the state’s investor-owned utilities.

At the nation’s largest public power system, the Tennessee Valley Authority, twenty years of stagnation has ended and now a new period of population and industrial growth has begun. At the same time, the generation capacity from the last coal plants in TVA’s storied fleet needs to be replaced. Solar and battery deployment there has been growing, especially with the passage of the IRA, and new nuclear capability is approaching consideration, if Congress will let TVA build it.

But in the meantime, TVA is turning largely to new gas-fueled power plants to handle the growth, to retire the far dirtier coal plants, and to integrate more intermittent renewables all while providing a reliable, balanced grid. Its electricity is cleaner than that supplied in grid areas with far more renewables, thanks to its nuclear plants, but climate activists have nonetheless painted a bullseye on TVA’s back because of the plans for new gas-fueled power infrastructure.

It’s easy to take the physical reality of the grid for granted. Most of the fixed capital investments that underpin it were made decades ago. The transmission line that caused the deadly 2018 Camp Fire in California, for example, was 72 years old; its components snapped due to wear and tear made worse by years of inadequate maintenance from the utility PG&E. As such, the politics of climate change, and the centrality of electricity to that politics, often carries on as if the increase in renewable energy is the one and only goal, regardless of the implications for reliability, and regardless of the political and economic forces driving the renewables industry.

Ultimately a winning electricity politics must understand that, above all, the working class wants cheap and reliable service. If climate activists, in their zeal for the planet, don’t take those goals seriously, they will have no chance to win the decarbonization they want to see.

Last summer Bill McKibben spoke at a public listening session held by TVA to discuss the authority’s power plans. He'd trekked to Nashville from Vermont, where, he proudly announced, the legislature had just voted to move to 100% renewables. To close his remarks he implored TVA: “There’s nothing you can do more important than move off gas and towards renewable energy.”

McKibben had a world to worry about. The only thing TVA had to be concerned with was a reliable grid that could serve ten million people and a growing regional economy.

■

Matt Huber is a professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at Syracuse University. He is the author of Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet.

Fred Stafford is a STEM professional and independent researcher on the power system, decarbonization, and public power. His newsletter can be found at PublicPowerReview.org.