Ending the Spectacle of Infantilism

The youth mental health crisis speaks to the abnegation of responsibility among adults—liberals and leftists foremost. Unmediated expressions of distress in spectacle-oriented activities must be rejected for a mature, radical politics.

The prevalence of mental illness among young people has been framed as a social problem in desperate need of both awareness and attention. The largest national and international agencies are already attuned to the matter. According to studies done by the World Health Organization, one in seven 19-year-olds has experienced “a mental disorder.” In the United States, one in five people between the ages of three and seventeen have experienced “mental, emotional… or behavioral disorders,” according to Dr. Vivek Murthy, surgeon general under Presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden.

However, this very same official recognized only one social ill that might be causing their distress: the climate crisis. Economic insecurity or childhood hunger, for example, are not mentioned. It isn’t hard to generate a more plausible, if basic, hypothesis as to why American youth today seem particularly hopeless: their social and economic prospects are extraordinarily grim. Indeed, nothing seems to change—except the climate. Late Imperial blandishments regarding “freedom” by conservatives, or “tolerance” by liberals, ring hollow. We seem to lack credible promises for the future, as well as the words to diagnose our ills. Language itself is worn out—no wonder AI is so dumb!

There are social causes for mental disorder: the absence of a positive, universal ego ideal has led to a weightless existence for adolescents. Instead, their non-productive consumption habits continue to be regarded as representing allegedly novel, non-normative forms of being that, according to liberal adults, should be emulated and protected. But this institutionalized, adolescent acting as transgression, or desublimation, does not produce freedom; constant anxiety about recognition produces more obsession and self-fixation. This disposition has its roots in the liberal counterculture, and has combined with the bourgeois idea of protection to engender a particular kind of helplessness in young people—and the adults around them.

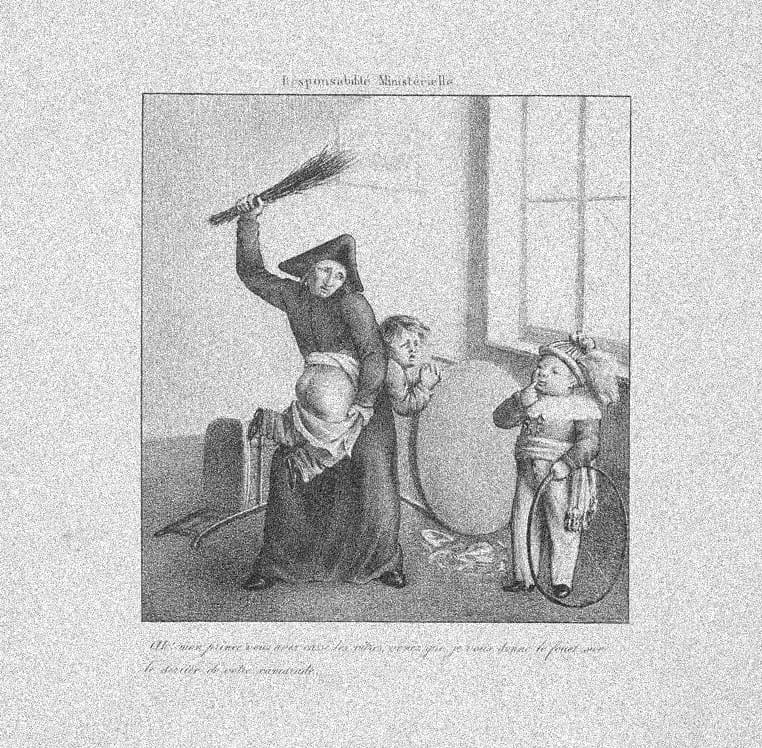

Helplessness and vulnerability are biological constraints on human infants. The prolongation and cultivation of the period of childhood dependency is an achievement of bourgeois societies, with surplus value expended on the children of elites, beginning most dramatically in Europe during the Renaissance with the growing power of Italy’s merchant class. Its much lauded humanism extended itself to dependents. Today, white-collar, college-educated parents across the political spectrum agree on one thing: children should be sheltered from material concern. Worry about one’s family is an important aspect of bourgeois ideology: parents who have accumulated enough family wealth hoard it so that it can be passed on to their feckless, irresponsible, but charming progeny. Professional-class people look to prolong the period of childhood dependency in order to promote juvenile optimization in preparation for a lifetime of intensive competition. The prolongation of dependency creates new social problems, with the most privileged adolescents demanding protection from ideas and confrontations on college campuses that allegedly endanger them, while working-class immigrant children labor in fields and slaughterhouses that present actual, imminent, and immediate dangers. The “well-being” of working-class, agricultural child laborers receives much less media attention than the travails of the coddled.