Self-Catfishing with Steroids

Steroid use is up, especially among young people seeking to display a particular physique online. The turning of the male gaze upon itself represents a radical form of alienation—and one with some nasty side effects to boot.

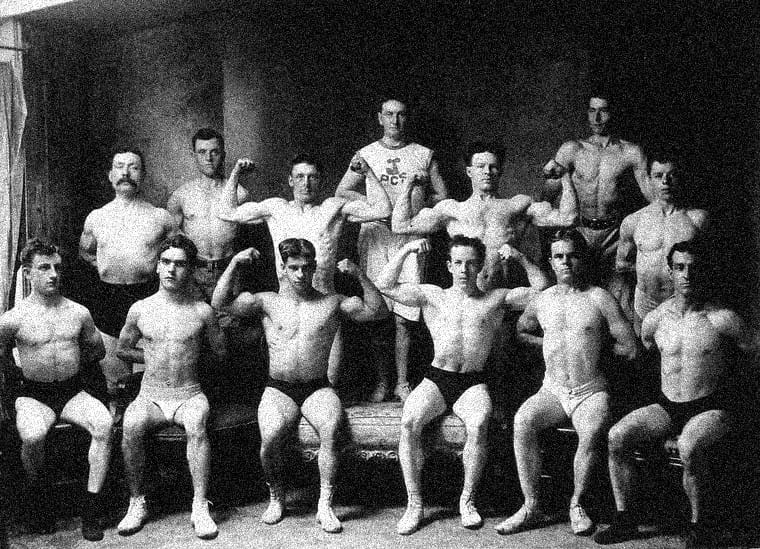

Constantly on display on social media from birth, a growing number of young people enter the world as social media content. So while it may not be the television screen that is the mind’s eye, their appearance on screens does become reality. For me, a 47-year-old Gen X’er, this can at times be difficult to fathom. I grew up in an analog era when pictures would be displayed in albums that might only see the light of day during family celebrations and holidays. Being born before the ubiquity of the video camera, my first steps were never immortalized; my first words were never captured and shared for viral validation. Photos captured a moment, a marker to reflect you were there: Disneyland, the Grand Canyon, a parade. Only a certain type of person who truly appreciated photography would try to capture every “precious moment.” Today’s youth exist, by contrast, in a self-inflicted surveillance state, one where we are all celebrities walking down a perpetual red carpet.

This pseudo-celebrity is all of us. Maybe some are less likely to acknowledge it because we have relationships that exist outside of the online sphere. Younger generations don’t have much of a choice in the matter: the online persona is the reality, so one needs to be ready for the photo op. The camera is ubiquitous, and the internet is eternal. There is no “online” and “offline” reality; there is only the online self. Every event, every casual hang with friends and family, is an opportunity to be on display for social media consumption. There becomes a pressure to constantly be aware of yourself as a character, or better yet, a “brand.”

Glamour Profession

Becoming a living billboard for brand “you” has created a growing population of young people who feel the best way to maintain their on-camera appearances is by using Image and Performance Enhancing Drugs (IPED). Research supports this trend, with studies showing that steroid use among adolescents has risen in recent years, fueled by social media pressure and the desire to achieve unattainable physical ideals. I’m not talking about athletes or aspiring fitness influencers, just young people wanting to maintain a photo-worthy physique. They know the risks and even display negative side effects when they stream their “fitness journey”—like massive back acne and depression when they cycle off the drugs.

Take the Tren Twins (2 million Tik Tok followers), for example. The 23-year-old brothers, Christian and Michael Gaiera, have achieved great social media success, amassing over one million followers across multiple platforms, including YouTube and TikTok. The duo takes their name from the IPED trenbolone that is popular among teens. While the Tren Twins claim they don’t use that particular muscle-building drug, they have no problem openly admitting to using other anabolic steroids.

Trenbolone, or “Tren,” is a synthetic anabolic steroid of the nandrolone group. It was designed to increase muscle growth and appetite in livestock. Despite being illegal for human use in many countries, trenbolone is used by some people to increase muscularity, strength, and fat loss. Part of its appeal is resistance to aromatization, which means it doesn’t convert to estrogen in the body.

Togi is another example of a young popular fitness influencer (731k followers on Tik Tok) that flaunts his chemically-enhanced physique and is rather cavalier about his steroid use, as well as the negative side effects he’s faced. Back acne, hair loss, and even the inability to produce testosterone naturally are treated as minor inconveniences, mere tolls on the road to achieving his “dream body” through rapid, unnatural growth. Why train for 3 years when you can get the same results in 6 months?

In an interview with natural bodybuilder and fitness influencer Jesse James, Togi admitted that steroid use was a perfect and simple inroad to fame: the “big reason I took steroids is cause I wanted to be famous…. Obviously, it worked out.” Togi’s transactional approach to fitness is not about wellness or longevity but simply about accruing social capital in the digital age. Togi and the Tren Twins’s reckless behavior demonstrates that steroids are no longer a game of shadows, but out in the open—flaunted and even celebrated.

Tren was never designed for human consumption and has plenty of disastrous side effects that fitness influencers constantly cite. As just mentioned, these include decreased testosterone production and hair loss, but also insomnia, rage, night sweats, gynecomastia (man boobs), and high cholesterol—just to name a few. A video by Dr. Chris Rayner on his YouTube channel called, “What The Hell is Tren and Why is Everyone Taking It,” has, as of this writing, over 1.6 million views. People want to know, but why do they care?

Whether influencers like the Tren Twins and Togi are actually taking Tren or not doesn’t matter; they’re popularizing it through meme culture. To their followers, the seemingly instant results are enough to outweigh the severe side effects. Tren and similar IPEDs are harmless in the minds of users because they can simply take a pill to handle the side effects. Gen Z and Gen Alpha are generations already predisposed to taking drugs for one disorder and another for the side effects. Can’t sleep because of ADHD meds? That’s fine, we have something for that.

There is a Veruca Salt mentality that exists in all of us, but in the era of everything on demand, I guess you can say we’re Veruca Salt on steroids. I want what I want, when I want it, because I want it… NOW! Are you hungry? Get food delivered to your home through an app. Need a ride and don’t want to bother with public transportation or taxis? In minutes, you can have a car show up at your door with a driver that you don’t even have to speak to. Need to read a book for a school assignment? ChatGPT can not only analyze the book and summarize it but can write you that report in seconds. Why should our physical appearance be any different?

Communal Alienation

The male gaze has been inverted, and now we are constantly looking into the black-mirrored abyss that is our phone screen, asking if we're the fairest of all. Pose your post-gym pump in the locker room and watch the likes populate.

At root, this is about how capitalism has penetrated our selves, commodifying even our bodies and identities. In a society driven by the logic of endless production and consumption, the self becomes yet another product to market, optimize, and consume. Young people born and raised in this hyper-surveilled digital environment internalize the pressure to perform and present themselves as idealized commodities for the gaze of others.

Steroid use among youth, therefore, can be seen as an extreme form of alienation. Studies have shown how adolescents experience a sense of disconnection from their own bodies as they alter their natural forms to align with unattainable standards set by social media and cultural aesthetics. Consider the case of young gym-goers who report feelings of inadequacy unless they achieve a "perfect" physique, often leading them to prioritize external validation over their well-being.

It’s worth noting that the communities of male validation created here actually go some way to overcoming the loneliness of young men today. Go to any gym, even a Planet Fitness, and you can find true camaraderie amongst the young men lifting and flexing in the mirrors. You don’t have to be athletically gifted or traditionally handsome to join or be respected. An awkward geek can be transformed into a Greek god in a matter of months. This is the cruel logic at work here: a community of young men being positive to and helping one another founded on radical alienation and bodily harm.

These examples illustrate the profound ways in which social pressures, as felt through the cruel funhouse of social media and even in-person communities, distort personal identity and exacerbate feelings of alienation. The body, a vessel of personal experience and connection, is transformed into a tool of production, sculpted to meet an abstract ideal perpetuated by social media and capitalist aesthetics. The pressure to maintain a “good physique” isn’t just about self-esteem; it’s about staying competitive in the social marketplace of appearance, which often correlates with opportunities for status, acceptance, and monetization.

Marx described alienation as the separation of individuals from their humanity in capitalist systems. Steroid culture—especially among non-athletes—embodies this principle. These individuals are alienated from their own physicality, compelled to alter their bodies to meet an external, commodified standard. The pain, risks, and side effects are accepted as collateral damage in the pursuit of a marketable self.

This is the cruel logic at work here: a community of young men being positive to and helping one another founded on radical alienation and bodily harm.

And We Die Young

There will be no “Just Say No” campaign for this rise in steroid use among young people. There will be no big-time police task force to take down massive steroid rings in gyms, and there won’t be people strung out in the street becoming part of the growing record number of homeless people in America, but young people will suffer irreversible damage from prolonged use. There are young men, and even some professional bodybuilders under 30, who cannot produce their own testosterone and, for the rest of their lives, will be on testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).

Some influencers are trying to buck the trend, presenting a goal of achievement where you push your body to its natural limits. I spoke with one fitness influencer who is trying to change the game by staying natural and not using IPEDs. Shaun Fury understands that even the “natural” bodybuilding world is filled with “fake natties,” but he is determined to stay on the steroid-free path, and it is starting to pay off for him. He’s caught the eye of several post-IPED-using influencers who see Shaun as authentic. But does authenticity matter in the mind's eye of our online persona? Can authenticity free one of the digital gaze?

Ultimately, we must confront the deeper structures of commodification that fuel this culture, including the relentless marketing strategies that commodify personal identity and body image. All of us feel the pressure to perform, and now perfect symmetry of my abdominals is just a shot away. Steroids are no longer “cheating”—it’s upkeep for your online avatar. What is the value of a “self” when I can edit my image chemically? Is it possible to create a world where self-worth isn’t determined by the symmetry of one’s jawline? Until then, the pressure to perform—both on-screen and off—will remain an enduring feature of our mediated reality, echoing the dystopian warnings of Videodrome.

■

Jason Myles is the host of THIS IS REVOLUTION>podcast and documentarian whose work can be found exclusively on Means TV.