The Responsible Socialism of Adolph Germer

Adolph Germer was a mineworker, socialist, and lifelong labor organizer who believed that organizing strategy must be both ambitious and practical. He adopted this orientation because he knew first hand both how difficult it was to win and how devastating it could be for workers when they lost.

In youth, one can be irresponsible. It’s one of the great things about youth. A lack of responsibility allows one to be bold, to speak and act with an eye toward truth, levity, and dramatic expression rather than consequences and communication. It’s fun, basically, and so it’s no real mystery why we all seek it out in some form or another, even well past the time when it’s appropriate to.

In many ways, however, youth is a state we never leave, and I’m not just affirming the old psychoanalytic lesson that we never escape from the psychic confines of the formative period of our early years. All sorts of exceptions are made in everyday life for some reprieve from adulthood. In intimate relationships, we are often coddled and tolerated by our partners in ways that would never fly in the outside world. In our cultural consumption, especially as of late, we can indulge in fantasies of heroism and villainy that only children could really believe in. Sadly, left-wing politics is also an arena within which youthful fancy can be extended into adulthood. Lenin famously castigated certain “childish” left-wingers who, by opposing absolutely proletarian rule with rule by leaders of a party, pathetically acted out their oedipal fantasies on party leadership.

Though Adolph Germer, the first field organizer of the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), hated the Leninists in his midst, he would likely have found much to agree with in Lenin’s diatribe against the irresponsible factions of disgruntled leftists who had not reckoned with the reality of power. Within six years of its birth in 1935, the CIO was responsible for more or less completely organizing the basic industries in the US. Prior to 1935, auto, steel, rubber, electrical manufacturing, and meatpacking were all unorganized. By 1941, they were all unionized industries.

In the CIO, Germer found what he had been looking for his entire life: a responsible organization. Responsibility is not much of a left-wing value, but for Germer, it was what distinguished playacting revolution from actually building power for the working class. When it comes to transforming the world into a freer and more equal place, many people can launch into beautiful flights of fancy on behalf of the cause, with inspiring rhetoric and dramatic gestures to match. Far fewer can say they’re going to do something both concrete and ambitious, and then actually do it.

When it comes to transforming the world into a freer and more equal place, many people can launch into beautiful flights of fancy on behalf of the cause, with inspiring rhetoric and dramatic gestures to match. Far fewer can say they’re going to do something both concrete and ambitious, and then actually do it.

A Half-Century of Failure

The Germer family arrived in America in 1888 and settled in a small mining town in southern Illinois with a sizable German population. There young Adolph completed his formal schooling at a Lutheran church and entered the mines with his father in 1892, at age eleven. In 1894, they joined a United Mine Workers of America strike, were blacklisted when the strike failed, and had to move towns. They struck again in 1897 and won, and the Germers returned to the mines under the terms of a union contract. As with so many of the CIO’s leaders, the absolute necessity of winning was impressed upon Germer at a young age.

Germer also shared with his CIO comrades an early love for Eugene Debs, and he unsurprisingly joined the Socialist Party in 1900. Even in his younger days, however, Germer had a distaste for certain flavors of radicalism, including the academic orientation of the followers of Daniel DeLeon in the Socialist Party and what he felt were the “idiotic tactics” of the Industrial Workers of the World, including the Western Federation of Miners’ disregard for contract sanctity. He was thus comfortable attacking both Samuel Gompers for suppressing labor militancy, on the one hand, and Big Bill Haywood for encouraging irresponsible versions of it, on the other.

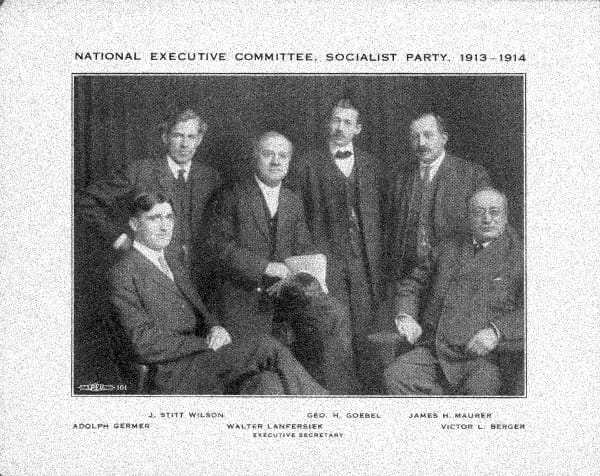

In 1914, Germer challenged his bitter rival, Frank Farrington, for the presidency of District 12 in the midwest. The International stepped in on behalf of Farrington, determined to halt the rise of any socialists to positions of leadership. When Germer made the ill-advised move of then proposing an investigation into the International’s “exceedingly high” overhead, the entire weight of the UMW bureaucracy came down upon his head. Shunned by the officers and no longer taken seriously by the rank-and-file, Germer left the UMW in 1916 to devote himself to his duties on the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party.

His wish for a larger role in the Party was promptly granted when he won the position of National Secretary. The SP’s embrace of Germer was no surprise: in an organization of middle-class theorists, Germer was not just for the working class but of it. Germer assumed office with high hopes and even secured $50,000 for an organizing drive, but the moment was not ripe for building the cause of socialism. The SP had taken a solid stance against the war, and subsequent government crackdown severely diminished its ranks. A turn of fortune followed from November 1917, but the new left-wingers that flocked to the party began contentiously to push more and more for Germany’s defeat, and thus for the SP to alter its anti-war commitment. Germer found the “Moscow-ites” annoying and disturbing and blocked every possible means of their ascendance within the SP, much as the UMW leadership had done to him and other fellow socialists. For this, Germer has been saddled with the epithet “right-wing socialist,” but he never vacillated in his hatred for Communism or apologized for his actions in the SP.

In 1919, the left-wingers abandoned the SP to form the Communist Party, and the SP went into freefall. Germer left for California, where for a time he worked as an organizer for the Oil Field, Gas Well, and Refinery Workers union and unsuccessfully ran to head the union. He returned to southern Illinois in 1924 to tend to his ailing mother, defeated both as a unionist and a socialist. He tentatively aligned himself with the swelling anti-Lewis forces within the UMW, and Lewis in turn let his goons break out the brass knuckles. All of the anti-Lewis maneuvering of the 1920s, of course, came to naught, and Adolph Germer, bent but not broken in both body and mind, returned to the mines in 1931, at the tender age of fifty.

In 1932, he formally left the Socialist Party, explaining that he could “no longer get the consent of my mind to pay tribute to a cat and dog fight in a morgue.”

Institutionalizing Militancy

One would not blame Germer for giving up at this point, or at least for reneging on his prior beliefs. Indeed, Germer’s biographer, Lorin Lee Cary, sees a shift in his orientation at this time; an abandonment of his prior socialist commitments and new desire to simply be a “labor professional.” Germer did belatedly abandon the SP, which had, under the direction of Norman Thomas, drifted further and further away from the working class. To Germer, the SP was more and more just a bunch of “college boys” debating “mush-head” ideas. In 1932, he formally left the Party, explaining that he could “no longer get the consent of my mind to pay tribute to a cat and dog fight in a morgue.”

But this turn away from “ideology” was at root a recommitment to his foundational beliefs. Germer had always charted a middle course between the business unionism of the AFL and the intellectualism and irresponsibility of the Communists, Wobblies, and other radical tendencies. No surprise, then, that when his erstwhile enemy John L. Lewis began striking out against the AFL establishment, complaining that they were squandering an historic opportunity to organize the unorganized, Germer reestablished contact. Lewis was predictably icy at first but eventually offered Germer the position of labor representative on the National Recovery Administration’s compliance council in Chicago. Then in November 1935, in the same month that the Committee of Industrial Organizations was formed, Lewis made him the CIO’s first field organizer.

As was the case with John Brophy, Powers Hapgood, and other former anti-Lewis UMWers, the shock at being again in Lewis’s employ must have been momentous to the now 54 year old Germer. But he did not have much time to reflect on his rapid change of fortunes: “In the ‘infant’ days of the CIO,” he later wrote, “we were pretty much like a colt when the barn door is opened in the spring, and it is turned loose into pasture, after a winter’s confinement. We kicked up quite a bit and sometimes we got a little out of bounds.” Soon after he was hired, Germer made contact with the United Rubber Workers (URW); he found their leaders livid with the AFL and the rank-and-file primed for action. Lewis came to address a huge rally on January 19th and exhorted the rubber workers to “do something for yourselves.” Three days later Firestone cut piece rates in the truck tire department, and in the arguments that followed, URW Local 7 committeeman Clay Dicks knocked his manager out cold. On January 28th, 1936, Firestone workers stopped their machines and sat down in the factory until the suspended Dicks was reinstated. The “sit down strike,” a tactic the rubber workers had been testing out since 1934, quickly spread to the Goodyear and B.F. Goodrich factories.

Germer arrived to “the CIO’s first strike” on February 22nd, five days after an eleven-mile picket line had formed around the Goodyear plant, with outposts bearing names like “Camp Roosevelt” or “John L. Lewis Post.” He was impressed by the takeoff but worried about the young militants’ ability to land with a settlement. The situation seemed on the cusp of rioting and violence: local non-strikers, some members of the Ku Klux Klan, sought confrontation, and Sheriff James Flower wanted to call in the National Guard. Meanwhile, Germer was pushing forward negotiations through endless contentious meetings, and on March 21st, Goodyear finally presented URW Local 2 with an agreement that members almost unanimously accepted. The union didn’t get everything it asked for, but it was a clear victory, further proven by the subsequent complete abandonment of the Goodyear company union and the ballooning of URW’s membership.

Leftists have always seen Germer’s actions in Akron, along with the CIO’s general role in the rank-and-file upsurge of 1936, as constraining militancy, and certainly particular segments of workers (the Communists and the Trotskyists, in particular) railed against Germer throughout. But the idea that rank-and-file energy would have exploded into a regional or national conflagration without the old guard stepping in is just counterfactual fantasizing. Goodyear President Paul Litchfield had been the manager of the Akron plant when the company broke a 1913 strike with the help of local police and eager vigilantes; it looked to him early on like 1936 would play out similarly. Without the strategic and tactical know-how brought by Germer and others, which included managing the governor, mayor, and other political authorities who could have brought in the guns, the rubber workers could have easily overplayed their hand, with the strike ending in violence and heartbreak. Germer was there to “institutionalize militancy,” and however one wants to view that phrase, he was successful in doing so.

With the rubber strike settled, Germer went to Michigan, where he found a similarly impatient rank-and-file in the United Automobile Workers. Though he played a smaller role there, he did help rein in the clumsy UAW leader Homer Martin from bungling the negotiations over the sit-down strike. From there he moved on to become CIO regional director for the state of Michigan. During his time in this position, his suspicions about the fickle and incompetent Martin were confirmed: in early 1939, Martin left the CIO to form a UAW within the AFL, a move that carried few workers out of the CIO but made Martin into a favorite punching bag for its leaders. From then on, when lashing out in speeches at the AFL as he often did, Germer typically saved a swipe for this “dictatorial” CIO defector.

The CIO’s Social Philosophy

On Labor Day 1934, Germer took it upon himself to lay out his mature social philosophy. “We have witnessed,” he wrote, “the social and industrial chaos resulting from our failure to sense and control the unseen forces of social development, and ask, is there any solution [to] our economic problems?” All around him he saw people looking longingly backwards for a lost form of life: referring to a speech of one such nostalgic who “wanted to go back to the ideals of our colonial forefathers”, Germer chided:

Some of our colonial forefathers, I am sorry to say, believed in the inalienable right of man to have property in his fellow man, they believed in chattel slavery—just as many people today believe in wage slavery. The flaming sword of the Civil war cauterized that idea from our national consciousness. Does that gentleman wish to return to the days of chattel slavery on his way back to the ideals of a former generation? Does he wish his wife and your wives to exchange their electric washing machines for the corrugated wash boards of their great-grandmothers? Does he wish to exchange the steam railway, the automobile, and the aeroplane for the speed and comfort of a “one-hoss shay?”... If these back to something critics keep going back far enough they may yet be able to twirl their prehensile tails around a limb and toss coconuts at each other.

Rather than looking backward, Germer thought it necessary to come to grips with the reality of the emerging consumer society: “As long as 70 per cent of the commodities produced by American industry have to be purchased by American laboring men, it ought to be obvious to even the dullest mind that labor can not be ground down to a subsistence level, or less, and still purchase enough to keep our factories operating.”

A tame statement, to be sure. But Germer ends on a clear note: “It is only through the creation of… an economic democracy, which will assure each man an opportunity to produce the things he and his family need, that we can stabilize society and assure a continuity of progress…. This objective can only be achieved by control by the workers of the means of production, and you can not control production of wealth until you realize the solidarity of purpose that comes only through intensive organization of your fellow workers.”

Germer thus had an essentially modern understanding of the sheer necessity of collective bargaining in a consumer society, but one that had to be upheld by workers against the employers “who are mentally working in the ox cart days.” He thus never gave up on the socialist belief that it was up to the workers themselves to assure social progress:

Without labor, there is no civilization. Without labor, there is no organized society. Without labor, there is no life worthy of the name. All of the burdens of the nations have ever rested upon the shoulders of labor. All the millionaires and billionaires, Napoleons of the financial world, from Jay Gould up and down have come and they have passed to the great unknown. The world never knew of their passing until it was told to us in the papers. They considered themselves as indispensable, but no matter where and when they go, industry went on and still goes on. But let Labor rest its hands and refuse to apply its skill for just one 24 hours, and a shriek of anguish and despair goes to the high heavens that the country is possessed by Communists and anarchists.

The absence of labor is felt everywhere, but the absence of millionaires and billionaires never! So let us appreciate our importance. Let us stand erect in the full majesty of our being.

Aside from the eternal encroachments of the “money crowd,” which would forever be hostile to labor, there were two immanent and imminent dangers to organized labor. The first was the regressive craft orientation of the AFL. In patrolling the narrow interests of skilled workers, “they are practically saying to the millions of unorganized that they have no interest in their welfare…. This is the most reactionary position ever taken by any section of the labor movement in any part of the world.” It was reactionary, for Germer, not just in callously dismissing a large share of the working class but also in undermining the power of organized workers as well. While bragging of the CIO’s accomplishments to the Montana State Industrial Union Conference in 1943, he cautioned that

The fact that we have over five million members doesn’t mean that our work is done. We are just in the beginning of the growth of the American labor movement. There are still some 30 or 35 million men and women to be organized in the United States. Every one of them is a danger to the labor organization. Every worker is a competitor of every other worker. The man and woman outside the union is a danger to those inside of it. We must get them in the union. That is the job for everyone in the C.I.O. A movement is not built by an individual no matter how great he thinks he is…. Every one of us in the C.I.O. can be in only one place at one time. All of us can be in five million places at one time. We must get our machinery working together.

The AFL, sadly, persisted in the face of the obvious need for industrial unionism “only as a definite obstruction to organizational work.”

The other danger came from the opposite end of the ideological spectrum. In his later years, Germer would be singularly devoted to fighting it.

Against the Moscow-liners

In 1940, Germer went west to help the ailing International Woodworkers of America (IWA). When Communist Harold Pritchett took over the union, anti-Communists exited en masse, and Pritchett turned to the CIO for resources to keep the IWA afloat. Germer’s characteristic advice to IWA leadership was that they should abandon their “factional policy” and focus on building the union. In addition to shutting down their 1940 convention over the angry protests of the anti-Communist opposition, Pritchett and company tried also to remove Germer from his post. The CIO's Organizational Director Allan Haywood stepped in in 1941 to get IWA leadership to reinstate suspended locals, and at their 1941 convention, membership decisively rejected the Communist leaders of their union, even passing a resolution to explicitly bar Communists altogether. The next month Germer secured a first contract with Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, and the union grew from roughly 30,000 to 50,000 members.

In his final stage with the CIO, Germer moved back to the midwest, where he took a dramatic step that cemented his reputation in leftist circles as a reactionary figure. At the behest of Walter Reuther, Germer seized control of the Communist-dominated Wayne County IUC on September 4, 1948. As Cary frames it, “Forceable reorganization of the Detroit council represented the CIO’s boldest move to that time in its campaign to compel unanimity on foreign and domestic policy issues.” In 1949-50, the CIO then took the final step of expelling Communist-led unions altogether, drastically lowering their membership count and paving the way for a reintegration with the now much larger AFL.

The expulsion of the Communists is commonly taken to be the practical end of the CIO as a political project. If the CIO was ever a truly radical endeavor, it had long ceased to be so by this point. The common explanation for this witch hunt is simply that CIO leaders got caught up in Cold War hysteria. Communists like Harry Bridges were ultimately good unionists, and Murray, Haywood, Brophy, Germer, etc. couldn’t accept this because they wanted the CIO to be a red-blooded American institution—yet another sad case of nationalism consuming radical working-class ambitions.

There is truth in this story, but it’s not the whole truth. Communists could be good unionists, but there were also examples—Germer’s experience with the IWA being ready-to-hand—where the “Moscow-liners” were clearly out of line with the rank-and-file. More generally, Germer and his allies saw Communism as a symptom of economic distress:

Communists are not born. Communist sentiment grows out of economic distress, out of poverty, out of misery. Give a man a decent income, let him have a comfortable home, enable him to pay his bills,... and you have a contented citizen. You have a loyal citizen that the Communists cannot reach with their treacherous propaganda….

We have extremes on both sides and labor is caught in the middle. We have Fascists in the United States. Fascism gets its following by pointing the warning finger at the Communists, “If you don’t join us, Joe Stalin will get you”, and the Communists on the other hand, point the warning finger at the Fascists…. Each extreme helps to build the opposite extreme. That is why Communists are of such great service to the Tafts and Hartleys and the Weirs and the Hearsts….

The appeal of Communism in a precarious society thus made perfect sense to Germer, but he also saw it as fueling the forces of reaction; a sad case where, in Bayard Rustin’s words, “the felt need deriving from a perception of fundamental and historic injustices… conflict[ed] with the required political strategy.”

A Responsible Organization

In 1940, Germer told the Washington State Industrial Union Council that “the CIO is a responsible organization. It should never, and I hope it will never, permit irresponsible individuals to conduct its affairs and shape its policies.” He reiterated to the Utah State Industrial Union Conference in 1949 that “the CIO is not the place for anyone who shirks his responsibility.”

Like all of the miners in the CIO, Germer had internalized from an early age the devastation that followed from disorganization and losing strikes. Not that failure was wholly avoidable, but he detested workers’ organizations that either tolerated disorganization as an unfortunate requirement of doing business, or prioritized ideology or foreign policy to the detriment of building powerful working-class organizations. The little “Hitlers and Mussolinis” in corporate boardrooms across the United States loved both a regressive craft orientation and ideological fits of fancy for the simple reason that both could be exploited to advance their own interests. Both, in short, were irresponsible orientations that distracted from the pursuit of the “full majesty” of labor’s being.

In this, despite his eventual abandonment of the Socialist Party, Germer never lost faith in the historic mission of the working class. Fulfilling this mission required the development of responsible organizations, but it was those responsible organizations that would allow labor to free itself on its own terms, and in so doing revolutionize the whole of society.

Well has it been said that labor is the savior of society; the redeemer of the race; and when its historic mission has been fulfilled, men and women can walk the highlands and enjoy the vision of a world without masters or slaves, a world regenerated and resplendent in the triumph of Freedom and of Civilization.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong keeps a Substack on labor & logistics at ontheseams.substack.com.