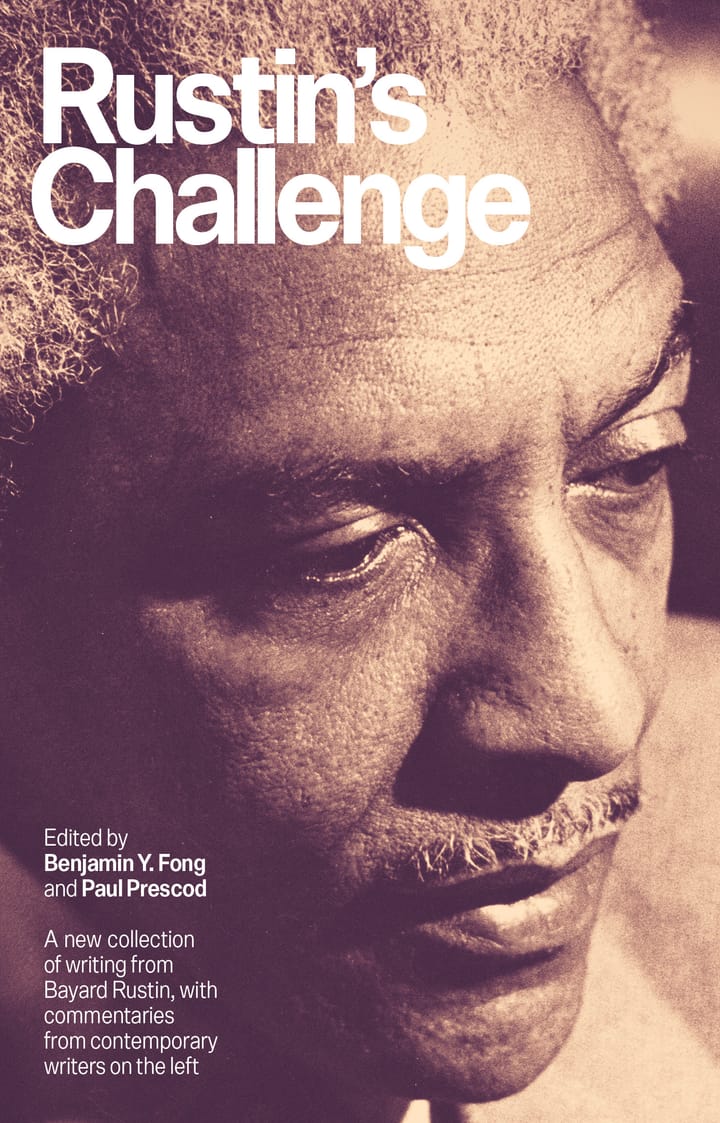

Rediscovering Humanity in its Absence

Peter Brown’s Wild Robot series transcends the anti-humanist moralism of much contemporary children’s literature and presents a much-needed vision of a habitable future.

There are a ton of children’s books about how great nature is, and most of them are not so subtly critical of human civilization. Sam Gribley’s whole life in the My Side of the Mountain series is an explicit rejection of society, and somehow Jean Craighead George makes it seem very cool with illustrations of plumping mills. There’s a new series of books each written from the perspective of an animal: A Horse Named Sky, A Wolf Called Wander, A Whale of the Wild, etc. Dave Eggers’ The Eyes and the Impossible essentially does the same. And there seem to be an infinite number of “love our earth” books for younger kids. In all, human beings are seen as interlopers and human society, if it’s present at all, as a problem or a constraint from which we ought to break free.

On first glance, Peter Brown’s The Wild Robot series appears to participate in this same anti-social glorification of nature and animality. There are no human beings in the first book, just robots and animals. Chapters go by where nothing happens except observations about the changing natural landscape. It’s all set in the near future where automation rules, and the sea levels are a few feet higher.

But almost immediately it’s clear that the series is not a part of but a response to what we might call the “Rousseauian” children’s literature—an acknowledgment of its basic critique, even an assumption of it, but also a rejection of its anti-humanism and an attempt at transcendence.

A container vessel sinks in the ocean, and crates of humanoid service robots wash ashore on a remote island. Most are destroyed, but one survives and is activated by a group of curious otters. Rozzum Unit 7134, or “Roz” for short, has known no other life and assumes she is home, albeit comically maladapted for her environment. In order to survive, she mimics the actions of the animals living there and ends up learning to speak “the language of the animals.”

One day, Roz slips while climbing down a rocky cliff and ends up crushing a goose nest, killing both parents and cracking most of the eggs. But one egg survives, and when it hatches, the gosling assumes Roz is its mother. Roz hesitatingly accepts the role, and soon the island’s animals, previously suspicious of and hostile to the new “monster,” become quite interested in how this hard metallic thing that doesn’t eat or drink is going to raise a gosling.

It’s a very difficult thing to do justice to the mother-infant bond: volumes of psychoanalytic and psychological theory have been devoted to it, and the payoff is essentially, “It’s very intense and important.” More concrete observations typically follow upon its absence, words being inadequate to the thing itself. It’s here where the primordial bond breaks that loss and terror and nascent independence enter the picture.

In Roz’s relationship with her son (she names him Brightbill), Peter Brown manages to capture and make metabolizable an important truth about that bond that is very difficult for children to process: that it was never really intact, at least in the way they think it might have been. Roz understandably does not know how to mother Brightbill and has to rely on the advice of other geese. She cannot fly or go in the water, and so has to mostly cheer his growing accomplishments from the sidelines. At the same time, her patient observations of the flight patterns of other birds allows Roz to impart unique lessons about flying to Brightbill—how to dive, circle, hover, and other things that most geese don’t do. As a result, Brightbill can do some things that other geese can’t and simultaneously doesn’t have what most other geese have.

It’s quite a complicated process to emerge out of envy, hatred, and disappointment with the inadequacies of your parents into something like gratitude and acceptance for the unique situation they raised you in: good at some things, lacking others. To some degree, it requires getting rid of the ideal image of your parents, of the idea that there was some original plenitude from which things have fallen. In Brightbill’s case, his mother literally eliminated his biological parents; she herself can only be really accepted with the knowledge that she destroyed that ideal image.

As Brightbill grows up, he becomes more curious about his mother: What is she? Did she grow up too? Is she alive?

The robot wanted to explain things to her son, but the truth was that she understood very little about herself. It was a mystery how she had come to life on the rocky shore. It was a mystery why her computer brain knew certain things but not others. She tried to answer Brightbill’s questions, but her answers only left him more confused.

Finally, Brightbill gets to his real question: “You’re not my real mother, are you?” Roz patiently explains how she came to be Brightbill’s mother, and Brightbill entertains a crushing possibility.

“Should I stop calling you Mama?” said the gosling.

“I will still act like your mother, no matter what you call me,” said the robot.

“I think I’ll keep calling you Mama.”

“I think I will keep calling you son.”

“We’re a strange family,” said Brightbill, with a little smile. “But I kind of like it that way.”

“Me too,” said Roz.

Eventually Brightbill has to follow his instincts and migrate south. Left to her own, Roz sort of shuts down, again mimicking animals going into hibernation for the winter. She wakes up to find the island covered in snow, in the midst of a particularly harsh winter. She finds dead animals all around, frozen stiff. “As we know,” Brown comments, “the wilderness is filled with beauty, but it’s also filled with ugliness.” Surveying her landscape, Roz announces, “Animals of the island! You do not have to freeze! Join me in my lodge, where it is safe and warm!”

The animals come slowly to join Roz in her lodge, where there is a well-tended fire. The lodge fills up quickly so Roz goes and builds more, teaching the animals at each how to keep a fire. Even after one of the lodges burns down, a possible testament to the hubris of interrupting the cold logic of nature, everyone agrees that a new lodge needs to be built, and the animals just need to be more careful. “The island became dotted with lodges that all glowed warmly through those long winter nights. And inside each one, animals laughed and shared stories and cheered their good friend Roz.”

It’s in moments like these that the Rousseauian impulse clearly present in the books is subverted. Nature is amazing, but it is also ugly. Technological imposition upon nature can be ugly, but it too is amazing. Certainly not a full-fledged eco-modernism at work, but there’s an opening that Brown provides for children that many authors won’t. It’s an opening to explore real ambivalence and contradiction about the way in which living beings exist on earth.

The end of the first book is no real ending at all. Spring returns, as does Brightbill, and then there’s a wild amount of action (especially compared to the generally slow-moving first ⅘ of the book) before Roz, broken and battered, is packed up on an airship to return to “the Makers.” It’s just no place to end a book, and I imagine my kids would have thrown a chair through the window if I didn’t have the second one ready to go.

For those irritated about all of the spoilers here, let me say that this is a children’s book series. These books are not for you. They’re to make new things appear for budding readers, or to make shared moments of understanding while reading aloud. Also, it’s been long enough that there’s already a film adaptation, which manages to ruin everything slow and exploratory and touching about the first book by clumsily rearranging details and insulting its audience with forced narrative tension. Film could only be done well in the twentieth century; it serves no purpose in the twenty-first.

The second installment in the series, The Wild Robot Escapes, begins on a farm. Our robot has been redeployed to aid widower Mr. Shareef and his two children, Jaya and Jad, in getting things in order at Hilltop Farm. It’s unclear at first if Roz is still really Roz—did the Makers wipe her memory?—but the minute Roz is left alone with the cows, it’s revealed that she still speaks the “language of the animals.” We learn that Roz was tested in various ways upon returning to the Makers and had to hide her true identity in passing these various tests as a “normal” robot would. Once cleared, she was reassembled with new parts and sold again as a salvaged unit—the right price for the struggling Mr. Shareef.

(Last comment about the film: in it, the Makers take a menacing and particular interest in Roz and her experiences, wanting to extract them for some unspecified purpose of the “company.” For Brown, by contrast, Roz’s CPU simply represents enough capital investment that the Makers are willing to go through the trouble to rehab her. There are no true enemies in The Wild Robot series, just the steady drumbeat of economic logic, one that the film is too impatient to capture.)

Roz adapts quickly to the farm routine, becoming an indispensable part of its operations, while dreaming of escape. She ingratiates herself to the family in various ways, and in particular to the children, who at one point order Roz to tell them stories to keep them entertained. Roz begins telling them about her former life in the guise of fiction, and they are, like young readers of the first book, transfixed. When Brightbill and his flock, hearing of a robot that speaks the animal language on a distant farm, arrive at Hilltop for a dramatic mother-son reunion, the children discover Roz cradling and speaking to a young goose, at which point they realize that all of the stories are true.

Through various twists and turns, Jaya and Jad help Roz escape from Hilltop. In many ways, Roz’s time with the Shareef family is the most dissatisfying part of the entire series. We learn that the missing mother in the family died in a farm accident, and that Mr. Shareef is broken, in body and mind, as a result of that accident. We know the children long for an emotional intimacy that they can only find in Roz, who, in turn, manipulates that connection for her own gain. We even catch glimpses of Roz’s own “worry and confusion and guilt” over her plan to run away from a family that she likes and clearly needs help. But all of this remains quite nascent: there’s no journey of healing for the Shareefs; this isn’t their story.

I wanted to know much more about this family and to find some resolution for them, but my kids were excited and unconflicted, relieved even, when Roz left the farm and began her journey back home with Brightbill. In this, their reaction mirrored that of Jaya and Jad, whose last words to Roz are, “Roz, we order you to run away.” The moral effect here is disconcerting: antihumanist, perhaps, but a good reminder that children are oftentimes more clear-eyed and resilient than adults. In the very truncated nature of Mr. Shareef’s story, Brown actually does a pretty good job of giving short leash to parental indulgence.

Roz and Brightbill make their way through a mostly rural landscape before encountering a city that they agree it makes sense to traverse rather than go around. Roz is spotted, and after a furious chase is captured by the RECO robots. She meets her designer, Dr. Molovo, who finds a clandestine means of returning Roz to her island and providing the resolution absent at the end of the first book.

The Wild Robot Escapes is the least interesting of the three books, mostly because it was required by the ending of the first. Brown does a good enough job of staying true to the slow pace and oblique observations of the series, but the existential questions are set from the get-go. There’s no great surprise when Roz asks Dr. Molovo, “Why do I fear water? Why am I female? Why was my body designed this way? Why does my computer brain know some things and not others?” They’re the exact questions lingering at the end of Book 1.

Still, Brown is given occasion in this book to do something only implied in the first: paint a portrait of near-future human civilization. In it, human toil is greatly relieved. The rural areas are littered with the remnants of human activity, the sea levels are higher, and there are hints at a general environmental blight with which the Shareefs and others struggle, but it’s no climate apocalypse. Though there is no mention of politics, it seems that enough has changed that a city could be “a glittering metropolis, where humans lived in luxury, all thanks to the tireless work of robots.” The city even has a very functional public transportation system. There are still the characteristic stresses of a city with new environmental challenges, but life goes on, and it actually seems pretty cool.

If there is a single moral imperative under which all writers of children’s books must suffer, agonizingly and with the very future of the human race dependent upon their abidance by it, it is to present a vision of human habitability in the contemporary world, or approximations thereof. Children today grow up internalizing way too much doom and gloom from parents and teachers too overwhelmed with their own concerns to reflect adequately on what they say, and when and why. As a result, it’s easy for children to wonder about our, and thus their, place in the world. To his credit, Brown offers up a scenario where the concerns of climate change are taken seriously but also one where human beings are seen as creatively adapting to new problems and greatly aided in their everyday tasks by advancements in robotics. It’s all in the background of the main action, but it’s an important consideration—and one that comes center stage in the last book.

The Wild Robot Protects, the last book in the series, did not need to be written, and I think it’s mostly better off for that fact. It’s not a book that was required by any narrative tension, and it’s not just one more in the series. Brown clearly felt compelled to write for himself, and for that reason, it can be a bit self-indulgent. But it’s also an attempt to craft a particular vision and lesson about a topic that is really too big for kids to grapple with but which they hear plenty about regardless.

At the end of Book 2, Dr. Molovo returns Roz to her island in a new robotic body, so that she can no longer be traced by the Makers. It’s here that we find Roz at the beginning of Book 3, finally at home and seemingly for good. But soon the animals catch word of a “poison tide” in the water, visible only as a slight shimmering but deadly to any creature that touches it. It soon surrounds the island, and Roz helps evacuate all the sea creatures inland.

After discovering both that her new robotic body is waterproof and also that she is immune to the effects of the poison tide, Roz decides she must venture out to find the source of the poison tide, to end it for good. After a long journey across old roads that are now under a few feet of water, tundra that has lost its permafrost, melting glaciers, and other features of a warmed planet, she discovers that a deep sea operation of the mining station Juggernaut is creating a toxic runoff—the source of the poison tide.

True to form, the Juggernaut is not managed by any treacherous villain but rather by Akiko Fuji, who is video conferencing with her husband and son the first time we meet her. “I’m worried about our family. How long are we going to live apart like this?”, her husband asks. When the call ends, Akiko begins to cry: “What am I doing? I don’t even like this job anymore.” Not only does Akiko not really want to be there, but she’s not even aware that her operation is creating the poison tide. “By our calculations, the runoff shouldn’t be traveling very far,” she tells Roz at one point.

It’s in the conversation that follows that Brown allows in a bit of the typical moralism of climate change discourse. Akiko tells Roz that they’re just following orders, and Roz snaps back: “You are just following orders. In a way, you humans are more robotic than I am.” The second-in-command George explains the utility of deep sea mining robots, and asks, “Can you believe we have to convince a robot why robots are important?” Again, Roz with the mic drop moment: “Can you believe I have to convince humans why their own environment is important?”

This brand of obviousness peddling is too of the moment; it felt sadly inevitable here. But fortunately Brown doesn’t indulge himself too extensively: Akiko tells Roz, “We know the environment is important. George and I both have children, and we want the world to be healthy for them.” After the mining station operations are shut down (through a wild bit of action reminiscent of the ending of the first book), Akiko is true to her word, and clean-up vessels remove most traces of the poison tide.

Humans cause problems, but we can also fix them. There is no lurking evil, just economic imperatives that we often resign ourselves to. The seemingly existential challenges of the modern world are at root tractable. These are good lessons to internalize, even if they’re conveyed with a bit too much attitude for my sensibilities.

It’s more than the environmentalist moralism that is at stake here, however. When Roz is not so subtly chastising Akiko and George, it just seems out of character. Who is this petulant know-it-all? What happened to the Roz who was content to sit and observe for long periods of time?

At a telling moment in the book, Roz discovers that the new robotic body she’s been given by Dr. Molovo has new capabilities beyond being waterproof. In her old body, her programming prevented her from acting with aggression, but she discovers that’s no longer the case in her new one. Under attack and with Survival Instincts blaring, “... that’s when Roz did something impossible. She did something unthinkable. She fought back.”

So Roz can hit things now, of her own volition. She too can purposefully inflict damage, and she knows that this means something important. There’s always a point in everyone’s childhood when that realization sticks; when an arm is broken, or parental outrage kicks in. So there’s something quite interesting to do with this moment, but in The Wild Robot Protects, it just sits there, and the action moves on. At no point does her newfound capacity and self-understanding really affect the course of the story.

I think Brown wanted something from this chapter that wasn’t forthcoming. Roz was evolving, and he could sense it, but without knowing what to do about it—other than clumsily having her start to hit things. If Brown writes another Wild Robot book—a 50/50 proposition from where I’m sitting—I imagine it will be to reckon with this evolution; to regain some control over a character that had begun to escape his grasp. But it’s possible that Roz no longer suits Brown’s purposes. Perhaps she’s grown up and finally escaped for good.

The anti-humanism of the present is a sign of radical alienation, one so complete that visions of material progress are easily eclipsed by its suffocating pessimism. Unfortunately this alienation has made its way into many walks of life, including children’s literature and the classroom, in such a way as to foreclose the future.

This is a bad situation for kids to grow up in. It’s a bad thing for kids to be presented with large problems that they cannot solve, and it’s a bad thing for them to internalize a conception of humanity as interloper on a pristine nature. It’s generally problematic when adults dump their problems on kids, but it’s especially so at this particularly alienated moment.

Peter Brown accepts this alienation as a starting point, and it’s why there’s no humans in the first book. But through that absence of humans, he allows a slow rediscovery of humanity. Kids can think about what a family is, about what our bonds consist of. They can imagine a future that is at the very least a realizable possibility in their lifetimes, one that has its problems but is affirmable and habitable. And they can reckon with a problem as massive as climate change (mostly) without the typical liberal moralizing and doomsaying.

My kids are now getting past the point where they want me to be reading to them, and I’m holding back tears letting that thought sink in. I’ll always remember certain reading experiences fondly—D’Aulaires’ Greek Myths, Ferdinand, Moonshot—but I feel genuinely lucky to have read The Wild Robot series to them (twice now) at this particular moment. A certain magic is created when books are meaningful to both adults and children, not in the same ways but nonetheless ways that contribute to a shared experience. That Brown manages this while also making metabolizable the social crisis of the present is a true artistic accomplishment.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong keeps a Substack on labor & logistics at ontheseams.substack.com.