What is the Pre-Political?

For decades, it has been fashionable to blur the line between what is political and what is not. This hasn’t been a good thing for either side.

What follows is the editorial introduction for Damage’s fifth print issue, “The Pre-Political.” This issue is currently being printed and will be shipping soon. Subscribe today to receive it in print!

With the twin Bernie Sanders presidential runs, the Left shed some of its more fringe trappings and entered the political arena. It was decidedly a good thing for a group of people accustomed to attending small protests and Marxist reading clubs to be overrun with newbies inspired by a popular democratic socialist to care about elections and to support basic bread-and-butter demands. But now the Left has swung in the other direction, so obsessed with the intricacies of Democratic Party politics that the Democratic Socialists of America could come out and claim the nomination of Tim Walz as Kamala Harris’s running mate as a win.

In theory, the Left should have one foot in the political arena and one foot outside of it, the latter building up trade unions and working-class associations (civil society organizations that influence politics) and projecting out a transformative horizon beyond immediate political considerations. If it leans too far toward the former, it becomes absorbed in the existing political horizon; if it leans too far toward the latter, it becomes insulated from political stakes.

We see a noticeable retreat from politics on the Left now that the Bernie moment has passed. This “pre-political drift” away from Sanders’s example is one of the unfortunate developments Jared Abbott discusses in his article, “On Learning (and Not Learning) from Bernie Sanders,” a comprehensive assessment of the legacy of the Sanders campaigns. This pre-political drift is also evident in the Left’s position on the crucial question of immigration, as Dustin Guastella contends in “Between Moral and Political Suicide.” By discussing immigration in blinkered moralistic terms rather than political ones, Guastella contends, the Left is “rolling out the red carpet for the Right.”

Whereas these two articles analyze a regression of the political to the pre-political, it’s common also to see the opposite today, i.e., the assertion of essentially non- or pre-political activities as overtly political. For example, in “The Regression in Psychoanalysis’s ‘Social Turn’”, Ricky Levitt and Christie Offenbacher argue that the imposition of identitarian “social concerns” on the essentially pre-political sphere of psychoanalysis weakens both analytic institutions and therapeutic practice. A similar “social turn” has taken hold in other liberal professional circles, which, as Ryan Zickgraf argues in “Can the Democrats Escape the Shadow of Woke?”, has contributed to the public perception of the Democratic Party as hopelessly out of touch. Many in the Party would love to distance themselves from this image, but they’re haunted by the influence of the “Shadow Party” and the general hollowing of politics in American society.

Whereas the Democrats are at the whims of cultural developments, the Right has more adeptly attempted to wield them. In “Conservativism as Postmodernism,” Matt McManus looks to the rhetoric of figures like the late Charlie Kirk and Chris Rufo, “postmodern conservatives” who dress up performative banality as “politics.” If this assertion of the pre-political as political is effective, perhaps it is because it is cynically and self-consciously undertaken.

Having made the distinction between the political and pre-political, it’s also on us to help define how the two domains relate. We might reject a silly slogan like “the personal is the political” and critique any manner of things that claim to rise to the level of politics but obviously do not. But we also need to specify how the pre-political affects the political, and vice versa. How precisely should we conceive of the realm of the pre-political (cultural developments, civil society organizations, morality, subject formation, labor organizing, etc.) in relation to the properly political (elections, parties, policy, etc.)?

George Hoare and Amber Trotter put forth a theory of the relation between proliferating rates of mental health diagnoses and the broader political breakdown of traditional forms of authority in “Overmedicalization and the Crisis of Authority.” The question of subject formation in its relation to politics is also at issue in “The Need for a Socialist Morality,” where Ana María Cisneros argues that the Left cannot cleanly separate moral from political questions, and that the attempt to do so is evidence of the Left’s having internalized an “individualistic morality [that] emerged with the rise of capitalism.” In “How the New Deal Ran a Tight Ship, and Built Some Too,” Bob Leighninger similarly argues that questions of graft and government efficiency cannot be separated from political ones. Without running efficient bureaucracies, it’s difficult to imagine ambitious industrial policy, and a political opportunity is created for conservative wrecking balls like Elon Musk’s DOGE.

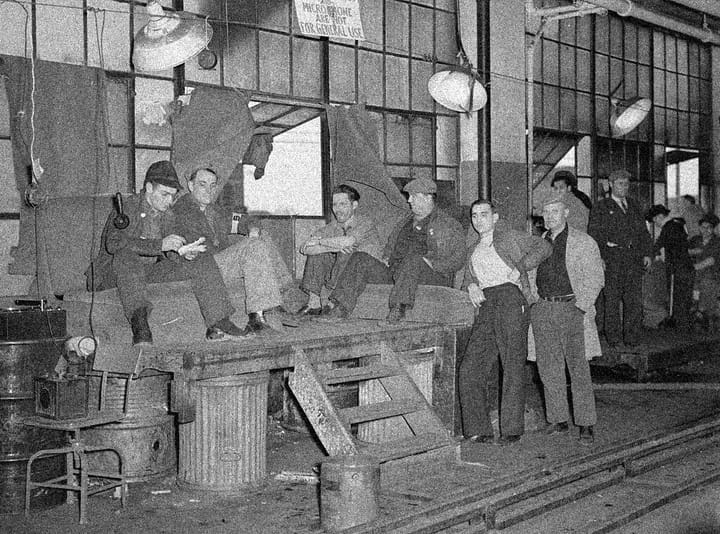

Garrett Shishido Strain looks to the 1930’s sit-down strikes in “Breaking the Hard Ground,” arguing that a key group psychological condition he calls “class confidence” underlay organized labor’s seminal upsurge and the political transformation that followed. Finally, Benjamin Fife closes the issue by investigating Moishe Postone’s portrayal of the Holocaust as an economically-senseless manifestation of anti-Semitism. As Fife contends, following Adam Tooze, this reading obscures the reality of the Holocaust as a brutal, messy, mostly technologically crude operation made feasible by the immense scale of the German war economy. As with all articles in this issue, “Horror as By-Product” raises the question of what consolations are offered by the elision of the difference between the pre-political and the political.

A brief plug before you dive into the issue: Damage is releasing its first book this winter, a new collection of the writings of civil rights organizer and socialist strategist Bayard Rustin. Rustin’s writings challenging the shibboleths of the Left are paired with commentaries from contemporary writers connecting those challenges to the present. We’d appreciate it greatly if you put in your pre-orders here.

■

Benjamin Y. Fong keeps a Substack on labor & logistics at ontheseams.substack.com.