Breaking the Hard Ground: Class Confidence From the Flint Sit-Downs to Today

The most famous union win in American labor history was a product of the conditions and organizing momentum of the moment. But it was also made possible by structure building and collective experiences that generated class confidence.

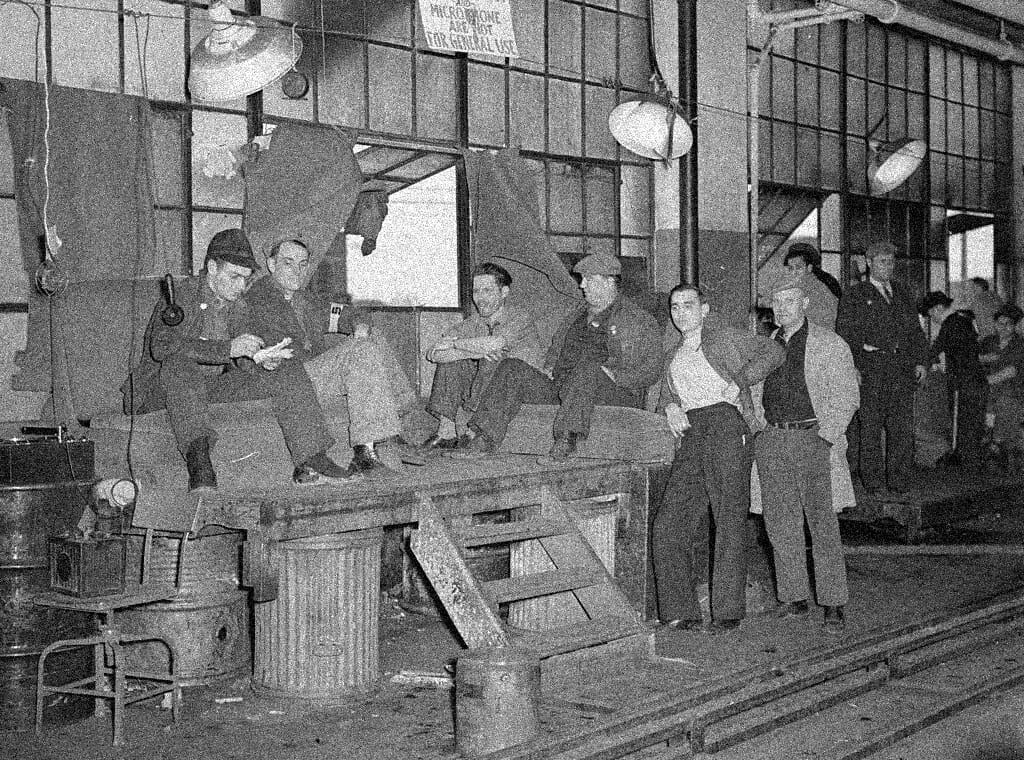

On February 11, 1937—44 days after their occupations of the Fisher Body No. 1 and No. 2 plants began in Flint, Michigan—General Motors workers won a landmark agreement. The one-page document included commitments to union recognition and collective bargaining over wages, seniority, work-life balance, and other working conditions, and a prohibition on discrimination or retaliation against union members. In a supplementary letter sent to Michigan Governor Murphy, GM also agreed, for a six-month period, not to support or bargain with company unions, or any organization of GM workers other than the United Auto Workers.

Before the sit-downs, there were many reasons to believe conditions were not ripe for a breakthrough against the world’s most powerful corporation. In June 1935, only 4,481 GM workers—less than 3% of GM’s hourly workforce—were dues-paying UAW members. In Flint, only 757 out of over 40,000 workers were members, and many GM workers regarded this small minority as “paid agents of General Motors and would have nothing to do with them.”

General Motors routinely flouted the law to undermine union drives—illegally firing and blacklisting union activists, employing spies to surveil union activity, and calling in police to bust up union meetings and strikes. The Congressional La Follette Committee exposed that GM spent millions on its vast anti-union espionage network and was the largest industrial client of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Flint was a paradigmatic company town: city ordinances forbade the distribution of union leaflets and the use of sound equipment for union demonstrations.

When UAW Vice President Wyndham Mortimer first canvassed the clapboard shacks of Flint workers’ neighborhoods in 1936, he lamented that “a cloud of fear hung over the city, and it was next to impossible to find anyone who would even discuss the question of unionism.” As UAW Communications Coordinator Henry Kraus put it, “Suspicion—the result of years of stoolpigeon activity—had reached the stage of a mania among Flint workers. The usual remark was that you couldn’t trust your best friend; you couldn’t even trust your own brother.”

The sit-down strikers nevertheless succeeded spectacularly. By the middle of October 1937, just eight months after the sit-down settlement, 400,000 workers across multiple companies had joined the UAW-CIO. By 1938, US union membership more than doubled to 24%. When GM workers held union representation elections in 1940, a majority of workers in 48 GM plants across the country voted to join UAW. By then, workers across the American economy—in transportation, meatpacking, electrical equipment, and steel—had joined together into new, mass-membership industrial unions.

What enabled a relatively small group of workers to engage in such dramatic action, and more importantly, what made them correct to assume that they had a majority of coworkers on their side? What made Flint workers believe that a successful sit-down was possible—especially when there was real potential for supervisors, police, and anti-union workers to violently suppress their occupation? As the UAW celebrates its ninetieth anniversary this year amidst an all-out assault by the billionaire class, returning to these questions of organization is more important than ever for charting labor’s future.

Class Confidence

One of the most common answers to these questions is simple: Flint workers—and workers in the 1930s more generally—were highly class conscious. But what is meant by “class consciousness”?

In The Making of the English Working Class, historian E.P. Thompson defines class consciousness as “the consciousness of an identity of interests as between all these diverse groups of working people and as against the interests of other classes.” Similarly, sociologist Erik Olin Wright defines class consciousness as “the understanding by people within a class of their class interests.” While understanding one’s class interests and their relationship to capital is certainly important for collective action, these definitions underspecify the psychological link between understanding and action. After all, most workers today understand that wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a billionaire class and that unions are the most effective way to fight back—but too many remain hesitant to act on these beliefs by forming a union in their workplace.

Others define class consciousness teleologically, reading it backwards from militant collective action. As labor sociologist Rick Fantasia notes, “the extraordinary degree of working-class solidarity expressed in the labor wars of the 1930s has served as a virtual ideal-typical model of class consciousness….” According to these accounts, you know class consciousness when you see it. But narratives of a spontaneous explosion of worker self-activity mystify the origins of class consciousness and collective action.

As any union leader or organizer knows, in addition to class consciousness, workers also need confidence. In order to take the necessary risks to prevail in fierce new organizing and contract fights, workers must not only know their interests but believe they can win them—and constantly exude this confidence in interactions with coworkers. This confidence must also be grounded in reality: in the experience of and lessons from past struggles, in the righteousness of the current fight, and in a strong structure of workplace leaders. Reflecting on the sit-down success, Wyndham Mortimer put it succinctly: “We had confidence and a spirit of sacrifice that eventually enabled us to accomplish what many had thought was impossible.”

Class confidence was an essential psychological precondition of the sit-downs, converting understanding of class interests into militant collective action. Many accounts of class consciousness certainly include some element of what I’m calling class confidence. But by pulling out and specifying this concept, we can better understand the mechanisms that lead from understanding to action and back again.

So how did class confidence come about in the case of the Flint sit-downs? Certainly one factor was the prior accumulation of victories—especially at smaller employers—which gave workers in isolated communities a sense of collective momentum. But previous eras had seen individual victories fail to inspire worker action at scale. What was key in Flint in the winter of 1936-37 to translating this momentum in the broader manufacturing industry into aggressive class confidence in workers’ immediate workplace was something else: a structure of trusted workplace leaders strong enough that dramatic disruption could be met with solidarity rather than fear and repression.

Momentum Toward Flint

In May 1936, French workers began what many claim were the first mass sit-down strikes in modern history. By June, one-fourth of all French workers were on strike, and nearly three-fourths of strikes were sit-downs. At a meeting with French automakers in September 1936, where they warned him about the French wave spreading across the Atlantic, General Motors Executive Vice President William Knudsen dismissed the threat: “No, that could not happen in the United States…. The American people would not stand for them.” Just weeks later, the sit-downs arrived in the US auto industry, starting at smaller suppliers in the early fall before reaching General Motors in November. Workers sat-in at parts maker Bendix in South Bend, Midland Steel and Kelsey-Hayes Wheel in Detroit, and finally, at General Motors plants in Atlanta, Kansas City, and Cleveland.

Each of these victories contributed to a sense of momentum and inevitability. They revived a belief in collective action after years of defeat—most notably Fisher Body No. 1’s previous failed strikes in 1930 and 1934, during which AFL leaders bungled negotiations with the company and GM fired and blacklisted many left-wing union leaders. They also gave practical advice to would-be sit-downers. According to La Follette Committee Investigator Charlie Kramer, Flint worker-activists, especially those with ties to the CPUSA, had developed “a whole organizational plan as to what you do inside the plant and what you do outside the plant. This was an organizational plan which had been derived from the Polish experience, the French experience, and the Akron experience, and Midland Steel.”

Roosevelt’s election to a second term supercharged this growing wave. In the 1936 presidential elections, CIO leader John L. Lewis declared that electing pro-labor federal and state officials was essential for organizing the mass-production industries. Lewis had good reason for this belief: anti-labor politicians and judges had allied with corporate interests to undermine Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda and stifle unionization efforts under the National Recovery Act. Lewis and other CIO leaders created Labor’s Non-Partisan League, committing greater union resources and boots on the ground to electing Roosevelt than in any previous election. When Roosevelt won decisively, “union sentiment flamed up throughout the whole plant like a fire before a wind,” according to one account. A UAW leaflet following the election declared, “You voted New Deal at the polls, and defeated the Auto Barons—now get a New Deal in the shop.”

Equally important was the election of Michigan Governor Frank Murphy, one of many New Deal governors who took office in 1937. Previous governors had used state police to break up strikes. Murphy pledged to support workers’ right to organize. So important was Murphy to the union’s strike strategy that UAW leaders had originally planned for the Flint sit-down to start in January 1937, after Murphy assumed office. Toward the end of the strike, Murphy delayed deploying state authorities to enforce an injunction, giving union leaders critical space to reach an agreement with GM.

Structure of Leaders as Engine of Confidence

Too many accounts of the 1930s upsurge begin and end with momentum and ripe political conditions, leading to a false sense of inevitability. What’s left unexplained is how precisely the sit-down momentum took hold in Flint. This remarkable upsurge of militancy could have ended, as it did at many previous moments in labor history, in heartbreak, with the sit-downs isolated and defeated, never arriving in Flint. Most GM factories were not directly involved in the sit-downs, so clearly factors beyond momentum were involved in making the Flint sit-downs successful.

Here I will show how a carefully built structure of workplace leaders fostered collective experiences that gave workers the confidence to sit down or leave their stations and support the strike from the outside. This structure was also crucial for the seizure of Plant 4 and other moments that brought the strike to ultimate victory, but the focus of this analysis will be on what enabled the Flint sit-downs to happen successfully in the first place.

In June 1936, Wyndham Mortimer arrived in Flint to help prepare for a decisive confrontation with General Motors. A long-time auto worker who rose to prominence after leading an organizing drive at the White Motor Company, Mortimer understood that winning union recognition at GM required organizing “on a national scale for a national strike to win a national agreement.” Flint, a crucial node in GM’s supply chain, was essential to this objective.

Mortimer built on previous years of organizing by the Socialist Party’s League for Industrial Democracy (LID) and other left-wing groups, working with a small core of seasoned shop-floor leaders to rebuild a network of workplace leaders in Flint. He bought a copy of the Flint directory to look up the addresses of five thousand workers who had formerly been part of Flint's defunct AFL auto unions, and sent those workers a series of letters. Each letter, according to Mortimer, “dealt with a specific issue” and “hammered home the fact that the answer to the problem was the union.” Here’s one letter that took the issue of fear head-on:

It is fear of losing the job that keeps you from signing an application for membership in the union. I do not blame anyone for protecting his job…. But the hard cold fact is that you will lose that job sooner or later. If you do not lose it as a result of joining the union, you will lose it because a new machine will replace you… or because gray hairs appear around your brow…. You will lose the job for any number of reasons beyond your control, because the job does not belong to you. It belongs to General Motors, and your chances of keeping that job will be infinitely better when you join with your fellows in a union, and fight for job security….

Any worker who responded positively to these letters was asked to organize a house meeting with trusted co-workers, outside the view of GM management and their spies, to discuss unionization. Attendees were asked to organize other house meetings and invite more coworkers. Many attendees had been active in previous failed strikes and were persuaded through this process that the UAW’s industrial approach marked a break from the AFL’s timid, craft union approach. Mortimer called this systematic approach to recruiting leaders, “breaking the hard ground” and “leavening the dough.”

Over time, workers built a fairly representative structure of pro-union leaders across most areas in the plant. Here’s how Bud Simons describes the process and the result of their efforts:

Yeah, most of 'em [Fisher Body No. 1 workers] were scared. So we had… volunteer organizers that we'd set up. And I'd take them over into the [union] hall and Mort [Mortimer] would sign his name on their organizing card, see. Volunteer organizers… Well, then they knew someone, had a brother or somebody in the tool shop or the press room or any place else and they'd get a hold of him, see. And Mort, he'd come out about once a week. And here's all the guys that are volunteer organizers. Well, they brought their friends and got them signed as volunteer organizers. We had the goddamn place full of them. Hell, we must have had two hundred and fifty volunteer organizers in there (emphasis added).

These volunteer organizers informed their coworkers about successful strikes at other plants, answered workers' questions about unionization, built unity, countered anti-union intimidation and misinformation, and recruited more organizers.

Months later, Bob Travis replaced Mortimer as the International Union’s primary organizer in Flint but continued the organizing program Mortimer set in motion. In Travis’s words, “I always indicated that someday maybe it would be necessary for us to have a strike. But we wanted to make sure that when we did that, we would be able to protect our strike and win the strike.” Travis reiterated to worker leaders the importance of enlarging their leadership structure “so as to get representation on it from all departments.”

Intermediate victories accelerated leadership recruitment across departments. One of the most important of these occurred in November when “body-in-white” department workers at Fisher Body No. 1 held a mini sit-down over the firing of workers protesting speed-ups—the auto industry’s most deeply and widely felt issue—on their line. Within hours, the fired workers were back at work. Strike Committee Chair Bud Simons summarized the lesson from the victory: “Fellows, you’ve seen what you can get by sticking together. All I want you to do is remember that.” In the following weeks, “organization shot out from body-in-white into [the] paint, trim, assembly, and press-and-metal [departments].”

To be sure, Flint’s workplace leadership structure still had major gaps that could have ultimately imperiled the strike. GM employed 47,000 workers across more than 10 factories in Flint. The company’s massive Buick, AC Spark Plug, and Chevrolet plants had limited pro-union leadership coverage. When the strike began suddenly on December 30th, these gaps enabled the company to stoke an anti-union backlash when the sit-downs idled or slowed production at Flint’s non-struck plants. GM channeled anti-union discontent into a front group called the “Flint Alliance for the Security of Our Jobs, Our Homes, and Our Community.” This organization engaged in vigilante violence against pro-union workers and demanded Governor Murphy enforce an injunction to eject the sit-downers.

The late labor organizer and scholar Jane McAlevey popularized a “structure-based organizing” approach that Flint in many ways exemplifies. But contrary to a central tenet of McAlevey’s approach, Flint Fisher Body workers did not engage in a rigorous, majority-participation structure test before sitting down. There were several reasons for this, including concerns that exposing pro-union workers before the sit-down would result in mass firings and blacklisting and concerns that their factories would prematurely shut down if they delayed a sit-down, due to parts shortages stemming from other sit-downs.

This didn’t mean Flint unionists expected “momentum” from broader industry victories to spontaneously spur masses to action. They knew that without workplace leaders across every department instilling confidence and maintaining unity, the company could easily divide, intimidate, and confuse their coworkers into inaction. That’s why they focused on building a dense, representative leadership structure, while recognizing their limited ability to preemptively “test” this structure in confrontational action. But through leader-driven, confidence-building activities—house meetings, delegations to supervisors over workplace issues, and mass meetings in the lead-up to December 30th—they generated enough solidarity to achieve majority support at the decisive moment, even while only a minority of workers sat down. As Victor Reuther put it, “the company's return-to-work movement was not able to persuade the majority outside the plant to act against the minority inside.”

I would argue that this approach is key to building class confidence: not necessarily a “verifiable” majority or supermajority in preparation for collective action, but a determined, representative minority that has both a majoritarian focus and enough of an understanding of and an embeddedness within their workplaces to make mass collective action happen. In many ways, the current regime of labor law has veiled this key dynamic that was at the heart of the biggest labor upsurge in American history. As that regime crumbles under Republican aggression and Democratic fecklessness, it’s an opportune time to revisit the basics of building class confidence.

Rebuilding Class Confidence Today

Just as in the early 30s, today a high degree of public support for unions exists alongside a historically low unionization rate and extreme concentrations of wealth and political power. To break out of this interregnum, we must train our focus on tactics and strategies that rebuild class confidence. What can we learn from the sit-downs about how to do this?

A key lesson I’ve tried to draw out here concerns the twin dangers today of overly rigid structure testing and minority vanguardism. If Flint sit-downers had insisted on completing a majority structure test before their strike, they likely would have missed their moment. This lesson contravenes more rigid applications of structure-based organizing, according to which no leadership structure can be considered ready for militant majority action unless it has proven its capacity to engage a majority in lower-stakes action. The opposite is also true: unions have lost elections and strikes by falsely concluding that a majority of workers signing cards or a petition necessarily means you have a strong, confident network of pro-union workers who can lead their coworkers through the boss campaign to victory.

William Z. Foster summarizes the other danger of minority vanguardism in Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry, cautioning that organizing campaigns must “prevent the movement from being wrecked by company-inspired local strikes and other disruptive tendencies. The necessary discipline cannot be attained by issuing drastic orders, but must be based upon wide education work among the rank and file and the development of confidence among them.” Flint organizers certainly agreed with these ideas and sought to avoid premature strikes called by a righteous but isolated few. Still, the lack of organization in Flint’s larger factories nearly proved fatal to the sit-down wave.

How to navigate between these twin dangers? In order to organize today’s massive, high-turnover workplaces—auto factories, logistics hubs, and more—it’s necessary to recruit and train a broad, representative layer of pro-union workers across work areas, departments, and shifts who are willing to help organize their coworkers. Not everyone in this layer will be so-called “organic leaders” in the strict sense of the term—their degree of influence will vary. But without this broad layer taking various actions to build their coworkers’ confidence, the most influential workers will likely sit out the fight. The sit-down experience shows the virtue of recruiting any and all trusted, pro-union workers who are willing to do at least some amount of organizing, tracking the growth of this structure over time, and drawing on it to mobilize workers to mass meetings and other collective experiences that further build class confidence.

The sit-downs are also evidence that big wins tend to happen in the right political conditions and with existing organizing momentum. Today, we must look for opportunities to win elections, strikes, and first contracts at smaller, less-resourced employers to help set off industry-based momentum. But for this momentum to breach a Tesla or an Amazon, we must do the spadework of recruiting and training leaders, across every area and shift, at the largest, most strategically important worksites. Only then will workers have the confidence to believe in Eugene Debs’ famous declaration that the labor movement’s triumph “is as certain of ultimate realization as is the setting of the sun.”

■

Garrett Shishido Strain is a union organizer based in Richmond, California.