Why the CCC is DOA

Sunrise’s Civilian Climate Corps is a strong proposal. It’s a shame that the class struggle orientation needed to realize it is wholly absent.

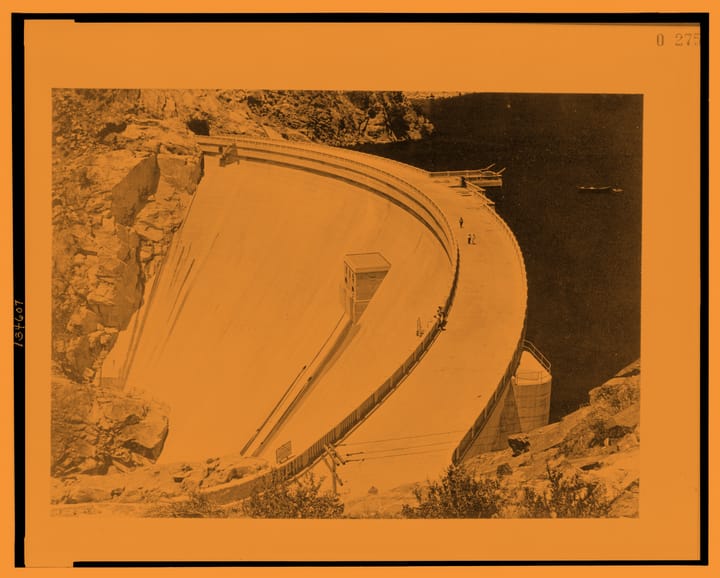

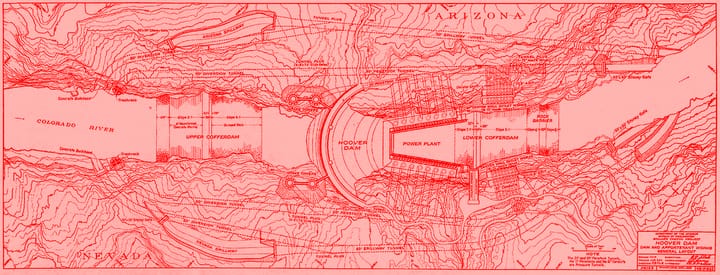

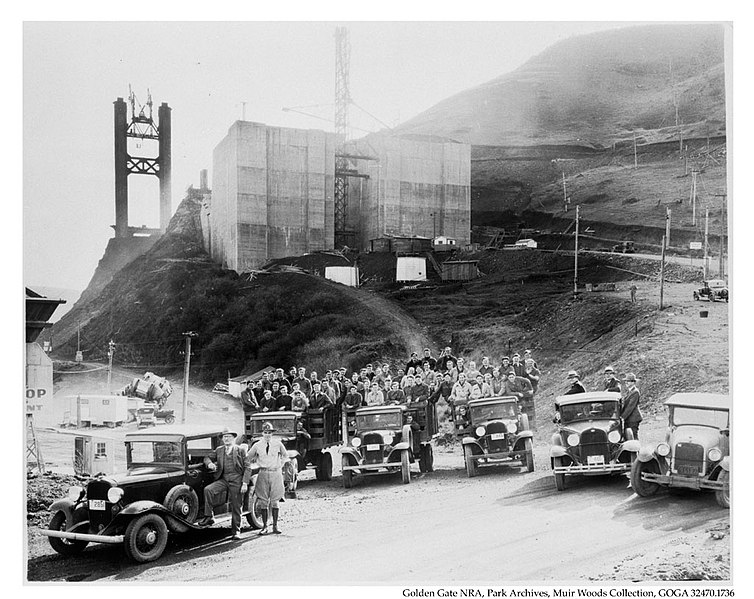

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of the most popular and successful of the New Deal programs. Its goal was to put people to work, solving the dual problems of America’s social and ecological devastation during the Depression years. Three months after its swift legislative passage in 1933, the federal government had organized 275,000 people—primarily but not exclusively young men—into camps across the country. When it ended nine years later, it had put more than 3 million to work, planted 3 billion trees, protected 20 million acres from soil erosion, and helped establish 800 state parks. It erected 197 large dams, three of which protected against flooding that had killed 120 people a decade earlier. It restored old American cultural landmarks, ranging from the Gettysburg battlefield to Native totem poles in Alaska, and built whole new ones like Colorado’s famous Red Rocks Amphitheater. On top of all that work, it provided social, cultural, and educational opportunities for its enrollees.

An enormously popular program, the CCC’s approval rating in a 1936 nationwide poll stood at 82%. Two-thirds of polled Republicans and even the party’s own presidential candidate that year supported the CCC. (Roosevelt nonetheless won reelection with the second-largest popular vote in U.S. history.) According to historian Robert Leighninger, it’s the only New Deal program to have had its own alumni association.

The CCC is obviously a historical precedent with immediate relevance for the present climate crisis, and this is why Sen. Ed Markey and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, along with the Sunrise Movement, are pushing their own updated proposal for a Civilian Climate Corps modelled on the original CCC. Call it CCC 2.0. As Sen. Bernie Sanders explains it in a recent email to supporters,

a Civilian Climate Corps (CCC)… will put hundreds of thousands of young Americans to work transforming our communities, energy systems, and lands—moving us towards a new, healthy green economy…. [N]ot only will the Civilian Climate Corps provide its members with livable wages and health care, … [it] will enable young people to receive the job training they need to obtain the many good-paying union jobs in our country that are currently unfilled because of a lack of skilled workers, and [it] will form the backbone of a new American economy that leads the world in clean, green industries.

Federal employment to do meaningful decarbonization work with benefits, a living wage, and a pipeline into unions… the CCC 2.0 proposal sounds like a potent program of class struggle. But with only NGO mercenaries armed with climate anxiety and half-remembered New Deal nostalgia, the proposal’s progressive champions are hopelessly outgunned by the business class.

What makes the CCC 2.0 uniquely potent

In her book The Politics and Civics of National Service, author Melissa Bass charts the progression of national service programs from the CCC under Roosevelt, through the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) under Johnson, ending on AmeriCorps under Clinton. AmeriCorps is still with us today; its most famous partner, Teach for America, embodies its spirit of substituting NGO grants for public goods and public jobs.

Markey and Ocasio-Cortez are not the first members of Congress in recent years to propose a revitalized CCC aimed at the climate crisis. For example, Sen. Chris Coons unveiled competing legislation around the same time—an expansion of AmeriCorps dressing itself in the garb of the New Deal, and touted by CEOs of multiple nonprofits that embody the trend toward privatization of service. And in 2019 Trump signed into law a 21st Century Conservation Service Corps, first proposed by Obama in 2012. Sunrise’s CCC 2.0 proposal, however, is far and away the strongest, and the most exciting for the Left.

Indeed, the CCC 2.0 proposal is a massive jobs program packed full of progressive and socialist ideas that go well beyond the CCC 1.0. In up to two one-year stints in the program, an enrollee would see meaningful work on climate resilience and decarbonization, a $15 minimum wage, healthcare, childcare, no restriction to only young people, no requirement to live out in camps or even away from one’s home, the explicit inclusion of skilled labor, explicit ties to union apprenticeships when the program ends, support for collective bargaining and union recruitment among enrollees, etc. Rather than antagonizing unions, who might otherwise see temporary workers doing the jobs they themselves want to be doing but for lower wages, those last features of the proposal might actually bring in those unions for a new terrain of organizing and dues drives.

All that sounds pretty great! But each reason why the proposal would attract young members of the working class is also a reason why it would invite a sure-footed counterattack by the capitalist class—and not just the usual political fight over the dollar amount of appropriations.

How many industries around the country depend on cheap youth labor? How many have organized to fight a $15 minimum wage? Are they just going to sit back and watch their potential workforce opt instead for actually-meaningful work on the government’s payrolls, where those young workers will earn more, enjoy more benefits, feel better for doing it, and end with a pipeline into union apprenticeships? Every single Chamber of Commerce is going to fight this proposal if it is seriously entertained. Republicans will be united against it, and most Democrats will join them.

It’s fine and necessary to take up these huge political battles—Medicare for All comes to mind—but there seems to be little awareness that this proposal cannot just be slotted in as an adjunct to a broader spending package.

And why is there little awareness of the class antagonism baked into the proposal? Here’s where New Deal nostalgia betrays us: the old CCC wasn’t a working-class offensive against capital, motivated by ecological concerns; it was a populist experiment, situated within the political economy of its time, and posed relatively little threat to business interests.

A sober look at the original

Back in 1933, when it sprang to life under Roosevelt, the Great Depression had truly ravaged the country’s economy and ecology. One in four Americans seeking work couldn’t find it, and over half of young people (ages 15 to 24) had merely part-time work or nothing at all. Capital wasn’t hiring—the number of nonfarm jobs shrank 24% from 1929 to 1933—so there were vanishingly few places that needed their labor. The CCC soaked up this surplus population of young men but largely without any competition whatsoever with private employers. Private enterprise wasn’t looking to create nature trails and clean up historic battlefields, nor were they interested in expanding their payrolls. Even the ecological devastation that the CCC mitigated was crucial to how Americans made a living: roughly 20 percent of the American labor force in 1930 worked on farms and just under half the population lived in rural areas.

That Depression-era economic context helps explain the CCC’s tremendous bipartisan popularity. Republican Congressmen and governors around the country, no friends of Roosevelt and the New Deal, recognized its importance for their states as well: the CCC allowed them to offload responsibility for impoverished families to the federal government. State leaders were more than happy to enroll unemployed youths in the federal CCC camps, where most of their meager wage was sent back home to their families. In early 1936, when Roosevelt began closing hundreds of CCC camps (one of his multiple failed attempts to balance the budget), he faced a practical mutiny from his own party—joined by many Republicans. And in 1938 only six members of the House voted against new appropriations for the CCC, despite Republican members numbering in the high double-digits at the time.

In contrast to that historical picture, let’s look at the political-economic conditions faced by CCC 2.0 today. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates current unemployment at 5.2%, with youth unemployment at 10%. Except in particularly rural and impoverished places, there are jobs, but they are shit jobs with shit benefits and shit wages that people reasonably don’t want. If the federal government can now offer employment to young people (and to anyone else, as CCC 2.0 is not merely a youth program) at $15 an hour and with various benefits like health insurance, there will be even more refusal to work the shit jobs that capital is offering. It’s a direct competition with private business and a huge threat to industries that rely on cheap youth labor, like fast food, restaurants, hospitality, and retail. That threat to their profits is precisely the class offensive baked into the proposal—a profound difference from the original CCC.

Building the wrong coalitions

Because the climate Left is not grasping the class struggle component of what they’re proposing, and because they’re so fixated on fighting climate change, they will likely paint any opposition to this program as insufficient concern about the climate crisis. “Rep. Joe Bob (D) opposes the CCC 2.0! He doesn’t believe in climate change! He’s a climate denier!” To which Rep. Joe Bob can respond with various policies that are in the works that do address carbon emissions, etc., thereby proving that the accusation is unfounded activist nonsense. He might even point to already-existing public-private imitations of the CCC focused on climate resilience at both national and state levels, all folded into the same federal apparatus.

For further proof that the bill and its supporters don’t realize its aggressive class dimension, one can check out the CCC 2.0’s legislative announcement from Markey and Ocasio-Cortez back in April—specifically, the fact that the laundry list of endorsers at the bottom is composed of Green and “___ justice” NGOs with a near total absence of labor organizations. NGOs are good at managing popular demands by channeling them into easy technocratic fixes that do not challenge capitalist class power; they’re less useful in cases where that challenge exists. The only union endorsers are those whose leadership has formed brokerage relationships with the Squad and related progressives: the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), whose PAC donated $200,000 to Sunrise last year; the Communication Workers of America (CWA), who have a long relationship to fellow endorsers and increasingly NGOist Working Families Party; and CWA-Flight Attendants, the union led by leftwing champion Sara Nelson, a vocal advocate of Sunrise, the Green New Deal, and even the Democratic Socialists of America. All are wrapped up in Green NGO activist networks like the People’s Climate Movement and the Green New Deal Network.

Beyond flight attendants, would a CCC 2.0 win over the unions that would ostensibly represent the workers doing the (skilled) project work, like weatherizing homes and installing solar panels, and that already lament the low wages in the renewable energy sector? As with the original CCC, which unions initially worried would cement the program’s subsistence wage in the federal government, there is plenty here to attract them—but only if they’re manifestly included in the political coalition. (Roosevelt wisely appointed a Machinists and American Federation of Labor leader as the director of the CCC.)

The exact same flaw drags down the similarly NGO-laden proposal for public power from fellow Squad members Rep. Cori Bush and Rep. Jamaal Bowman. Despite the potential (and need) for a coalition with unions in utilities and power, their legislation’s endorsers include a few dozen NGOs but only a single union—public utility workers for the tiny and fundamentally distinct Puerto Rican electrical grid.

Unfortunately the track record for working with those unions from the get-go on a Green New Deal, led by the same progressive legislators and NGOs, is notoriously bad. Without more backing of unions and their memberships, and without an organized campaign outside the professional-leaning ranks of Sunrise volunteers, the CCC 2.0 proposal lacks the working-class force needed to see it through.

In an interview with Evan Weber of the Sunrise Movement, The American Prospect’s David Dayen seems to conclude that the CCC 2.0 proposal is an unnecessary sideshow in the broader fights over infrastructure, but he doesn’t nail the precise reason—that the CCC proposal is doomed to failure because of the NGOist political orientation behind it.

What’s worth fighting for

The CCC 2.0 might nonetheless see the light of day, but in what form? At an event in Colorado earlier this week, Biden said plainly that he wants to create a Civilian Climate Corps and put young people to work fighting forest fires and conserving public lands. But he could make good on that vague promise in various ways that fall well short of the CCC 2.0 proposal championed by Sen. Markey, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez, and Sunrise.

A new CCC could slip through just like existing Corps programs nobody’s heard of, with AmeriCorps’ public-private organization and no connections to unions, and largely devolved to disjointed state Corps programs. Just a week before Biden’s Colorado speech, the state unveiled its own AmeriCorps-based Colorado Climate Corps, for example. Or maybe a CCC 2.0 would simply be woefully tiny so as not to pose a threat to business. Though its progressive supporters have called for $20 billion a year, Biden’s proposed $1.25 billion is only enough to employ 25,000 workers annually—roughly the size of AmeriCorps today, and a tenth of what the original CCC employed in its first three months alone. A cynic might say that this was the endgame all along: organize around a radical program to attract activists, and then claim victory when a severely watered-down imitation gets included to little fanfare. When Sunrise snags the enthusiastic support of Chuck Schumer but not of any relevant labor unions, one has to wonder.

Biden’s broader infrastructure package, on the other hand, harkens back to a different New Deal program: the Public Works Administration from 1933 to 1944—though mostly in appropriations, not in the highly standardized, controlled, deliberate project management to weed out graft and to ensure quality construction. Sadly, unlike the PWA, the Biden infrastructure money that would be shooting off into various pursuits will not be formed into people’s minds as an explicit program by explicit politics that should be rewarded with more votes. Damage contributor John Terese recently called this federal spigot “the invisible hand of the state: a referee who will occasionally assist the players but never partake in the game itself.”

The Left should focus its energy on demanding improvements in the infrastructure package, rather than a quixotic attempt to win an aggressive program under the CCC brand without an aggressive political coalition to match. Nostalgia among highly-educated liberals for the ecological dimension of the original CCC in this case only veils the political economy that enabled it, and in turn what is possible in our current state of working-class demobilization.

■

Fred Stafford is a STEM professional on the Left. His writing on public power and infrastructure has appeared in Jacobin.