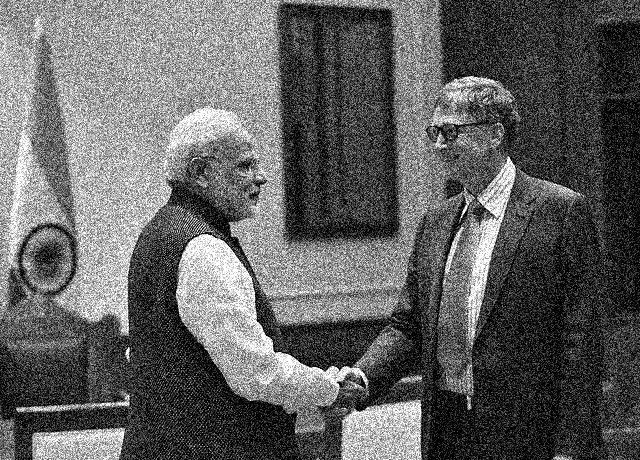

Bill Gates in India

Global public health interventions are used by philanthropic elites to promote their own favored technocratic disease fixes at the expense of both democracy and life.

A slightly-modified excerpt from The Givers That Take (2021), which can be downloaded here for free.

Global public health interventions are used by philanthropic elites to promote their own favored technocratic disease fixes at the expense of both democracy and life. One notable example is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s commitment to AIDS research and prevention. In 2002, the Gates Foundation decided to locate their first overseas office in India to help them combat the growing AIDS epidemic in the region. This followed on the heels of the World Bank’s own failing and destructive attempts to fight AIDS on the subcontinent. This new foundation-driven project, known in India as Avahan, ran from 2003 until 2010 at a total cost of around $300 million.

In this huge Gates-backed health project, no efforts were made to improve India’s increasingly privatized health infrastructure. Instead, the Gates Foundation pumped millions into creating a new layer of non-profit organizations that were given the goal of telling truck drivers, migrant laborers and sex workers that they should use condoms. Rather than seek institutional solutions that could minimize the death toll from India’s AIDS crisis, the Foundation focused their attention on individuals and their sexual choices in addition to attempting to developing new medical silver bullets.

Gates can point to the limited success of Avahan’s educational initiatives in preventing the spread of AIDS, but it’s recognized now to have been an overall failure. The long-term consequences of this intervention still need to be understood, especially as similar AIDS projects run by the Gates Foundation in Africa look to be failing. As Kim Yi Dionne states in her book Doomed Interventions: The Failure of Global Responses to AIDS in Africa,

Billions of dollars have been spent to curb the AIDS epidemic. Donor governments spent $8.6 billion in 2014 alone on anti-AIDS initiatives. While this outpouring has had a tremendous impact—particularly in increasing treatment access in resource-poor countries—many donor-supported AIDS interventions have shown little objective impact on stemming the spread of HIV and bettering the lives of those affected by AIDS. For example, between 1997 and 2006, only 18% of projects in the World Bank’s African Multicountry AIDS Program had satisfactory outcomes according to internal evaluations. When a mobilized international community commits billions of dollars to fight a disease, what impedes its efforts to improve outcomes for intended beneficiaries?

It should also be borne in mind that, for obvious reasons relating to funding pressures, critical reviews of Gates’ philanthropic initiatives remain few and far between. One particularly scathing commentary that was published in Forbes India (in 2009) nonetheless had this to say:

When it started on the ground in 2003, Avahan set for itself three goals: Arrest the spread of HIV/AIDS in India, expand the programme from the initial six states to across the nation, and develop a model that the government can adopt and sustain so that the project could be passed on to it. More than five years later, Avahan hasn’t achieved any of these goals. Doubtless, the initiative has made a dent into the HIV/AIDS problem, but the impact is marginal for a bill of $258 million. And now Avahan is leaving, handing over the reins to the government-run National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO), which doesn’t want to inherit it. It is too expensive for the budget-starved establishment that is as nimble as a sloth.

The bigger picture here is that billionaire philanthropists like Bill Gates are unwilling to adopt the necessary political tools that have a chance of resolving the global AIDS crisis. As one writer recently put it: “The World Bank and the Gates Foundation—the biggest funders of AIDS prevention” simply “cannot be entrusted” with the task of resolving the AIDS crisis because “they have clear interests in the very policies (debt service, structural adjustment and patent laws) that have created the problem in the first place.”

Likewise, speaking in 2006 at the XVI International AIDS Conference in Toronto, Canada, Gregg Gonsalves called for the “need to re-politicize AIDS.” He made it clear that the so-called humanitarian interventions being orchestrated by the philanthropies of the super-rich are failing the world because their aid is organized in a way that is both unaccountable and undemocratic. “No wonder things arenʼt getting better,” he stated.

Weʼve created a system designed to fail. Yet in the margins of this system, there remain men and women, true heroes, who are largely forgotten, unknown, ignored or reviled by those who make this machine run. Itʼs not Bill Gates or Bill Clinton who have made a difference in this [AIDS] epidemic despite their being treated at this conference as some sort of royalty—the seduction of the money and power they represent have blinded us to what theyʼve really delivered…

We are at a terrible anti-political moment right now, where the powers-that-be have taken our rhetoric and told us that everything is fine—weʼre on your side; you can demobilize and leave the epidemic to us.” That is the pernicious message of this conference. Donʼt believe a word they say.

It is worth reiterating that the drugs needed to treat AIDS have been available since the mid-1990s, but the corporations producing them have refused to make them affordable. Worse still, corporate giants, including Microsoft, had lobbied hard to introduce TRIPS (which came into effect in 1995), a legal precedent which effectively made it illegal for poorer nations to produce generic versions of life-saving drugs. Gates and his like ultimately believe that Big Pharma has a God-given right to profiteer from AIDS, or any other disease for that matter.

It’s not easy to walk a fine line between amassing immense profits from Microsoft and presenting oneself as a global health savior. Just the day after Gates launched his $100 million contribution to fighting HIV/AIDS in India, he merrily donned “his Microsoft hat” and announced that his company was investing $400 million into expanding their corporate operations in India. The person selected to manage the HIV initiative was a former director of the global management firm McKinsey & Company.

The links between Gates’ corporate friends and his powerful philanthropic health predecessors can be seen in the fact that the former chairman of Microsoft India, Ravi Venkatesan, has now spent the best part of the last decade serving on the board of trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation. In fact, the year that Venkatesan joined Rockefeller was also the year that Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP first gained a parliamentary majority. And Venkatesan, in his excitement of this rise to power of the far-right, wrote: “Almost every CEO I’ve talked to, before and after the polls, believes that Modi is a shrewd, pragmatic, and decisive leader, who can kick-start economic growth and development in India by fostering a more business-friendly policy environment.” In September 2019, the Gates Foundation honored Modi with a “Global Goalkeeper Award” for the “successes” of his anti-corruption initiative—the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan project.

Every year millions of Indian women are forced to choose to be sterilized in lieu of having access, or being able to afford access, to any form of meaningful public healthcare. Billionaire philanthropists have of course ruled out the possibility of supporting socialized health provision, and instead continue to push forward new technocratic solutions to limit the reproduction of those deemed by the state to be unfit to reproduce.

Thus, on November 13, 2014, to much international fanfare, the Gates Foundation, working in collaboration with Pfizer, announced in the pages of the New York Times that they were rolling out, for wider use, a product called the Sayana Press—a product whose main selling-point was that it provided a more reliable means of delivering Pfizer’s already controversial Depo-Provera contraceptive to the rural poor. The numerous critics of this contraceptive quickly pointed out that in addition to the many problematic known side effects of using Depo-Provera, another issue was that its use was associated with increased risk of spreading HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, it was not coincidental that the day before the New York Times ran their 2014 Sayana Press puff-piece, they had featured an article exposing the deadly nature of India’s “sterilization camps”. Hence Pfizer’s Sayana Press was, not so subtly, presented as the latest technocratic solution to India’s violent sterilization problem.

Under friendly pressure to act from billionaires like Bill Gates, in 2016 Modi announced that the Sayana Press injectable contraceptives were going to be delivered to the poor for no cost. The New York Times, in reporting on these “modernizing” changes, remained perplexed that “the keenest opposition to these newer methods of birth control” originated “from some women’s activist groups that distrust the safety of these methods and believe that profit-hungry Western pharmaceutical companies are pushing them.” They added that these activist groups, many of whom had also opposed the use of such contraceptive drugs when the country was run by the Congress Party, were concerned that the drugs “had not been proved safe and could be used coercively”. But the reporters didn’t give any serious credence to the fact that these remain very legitimate fears, especially given the anti-Muslim sentiments of Modi’s far-right regime.

Writing in 2015, Betsy Hartmann and Mohan Rao drew attention to the Gates Foundation’s role in helping the Indian state reverse all the gains that had been made possible by the “sustained and courageous efforts of feminist, health and human rights activists” who “have taken a leading role in exposing sterilisation abuse, pushing for contraceptive safety, and demanding systemic reforms.” They wrote:

The top-down, neo-Malthusian prerogatives of the [Gates-initiated Family Planning 2020] FP2020 mesh well with other features of today’s international development industry, including its managerial ethos, obsession with measurable outcomes and technical fixes, and the privileging of the private sector. Add to this the immense power of wealthy philanthropic interests, such as the BMGF [Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation], that wed technocracy with plutocracy.

India’s efforts to limit population growth do not stop there. The subcontinent has one of the largest and most pervasive state-operated surveillance systems in the world. Known as Aadhaar, this Unique Identity (UID) surveillance project was initially rolled out in 2010 and overseen by Nandan Nilekani, the cofounder of India’s powerful IT giant Infosys. To minimize public opposition to this Orwellian scheme, at first the project was deceptively sold to the public as a voluntary initiative that would give the poor and the undocumented a digital identity that would not only help them access state benefits but would also prevent fraud. This marketing fiction, however, didn’t last long, and by 2012 it had become clear that coercion was to play a central role in the push-out of Aadhaar. Indian citizens soon found out that they would be denied benefits if they refused to allow the state to digitize their biometric data through fingerprint and retina scans.

It is interesting to note that during Aadhaar’s early days, the BJP had stood opposed to the Congress Party’s intrusive intervention into public life. In fact, in 2014, just prior to his becoming Prime Minister, Narendra Modi had characterized the project as a “political gimmick” and as a potential threat to India’s national security (owing to the scheme’s origin in foreign surveillance corporations). Nevertheless, upon riding to power in the 2014 national elections, Modi and the BJP quickly became devout advocates of the surveillance project, which “emerged as a foundational component of the BJP’s governance plans”. All pretence of voluntary compliance with the scheme were now dropped, with registration strictly enforced by the state.

The Digital Empowerment Foundation has regularly exposed the failures of Aadhaar, and in early 2018 they pointed out that rather than help the poor, over the “last two years we have seen that Aadhaar has only made access to schemes and entitlements more difficult.” Legal researcher and activist Usha Ramanathan says Aadhaar has “innovatively violate[d] norms of privacy” and created a structure that can be utilized as a tool of mass surveillance. Nearly the entire nation’s biometric data is now stored by the government, and the immense power that such data yields in the hands of Modi should rightly concern the political targets of his regime.

This is not a concern, however, that is shared by Bill Gates, who remains an enthusiastic supporter of Modi’s surveillance system. Ever the techno-optimistic, Gates says:

Thanks to the work Nandan [the head of Aadhaar] is doing, the world is moving closer to the day when everyone will have access to an official ID. The sooner we can achieve this goal, the sooner the world’s poorest residents will not only be able to prove who they are, but also realize their aspirations for better lives.

For capitalist oppressors like Gates, surveillance of the global polity is essential in their ongoing efforts to help members of the billionaire class realize their own “aspirations for better lives”, or at least lives in which they gain even more power over the rest of us. But access to a biometric ID card is not solving the deeply inequitable distribution of wealth and power in India, and nor will it do so for the rest of the world. For anyone serious about helping the global working class actually improve their lives, it should be clear that a starting point for enabling such dreams is to expand their democratic rights, not restrict them by forcibly incorporating them in a global surveillance network.

■

Michael Barker is a support worker at a school where he also acts as a Union rep, and is an Assistant Secretary to the Leicester and District Trades Union Council. He is the author of Under the Mask of Philanthropy and The Givers That Take.