The Left Did A No Growth

Degrowth isn’t just political poison, it is also based on faulty economics. The sooner we abandon it the better.

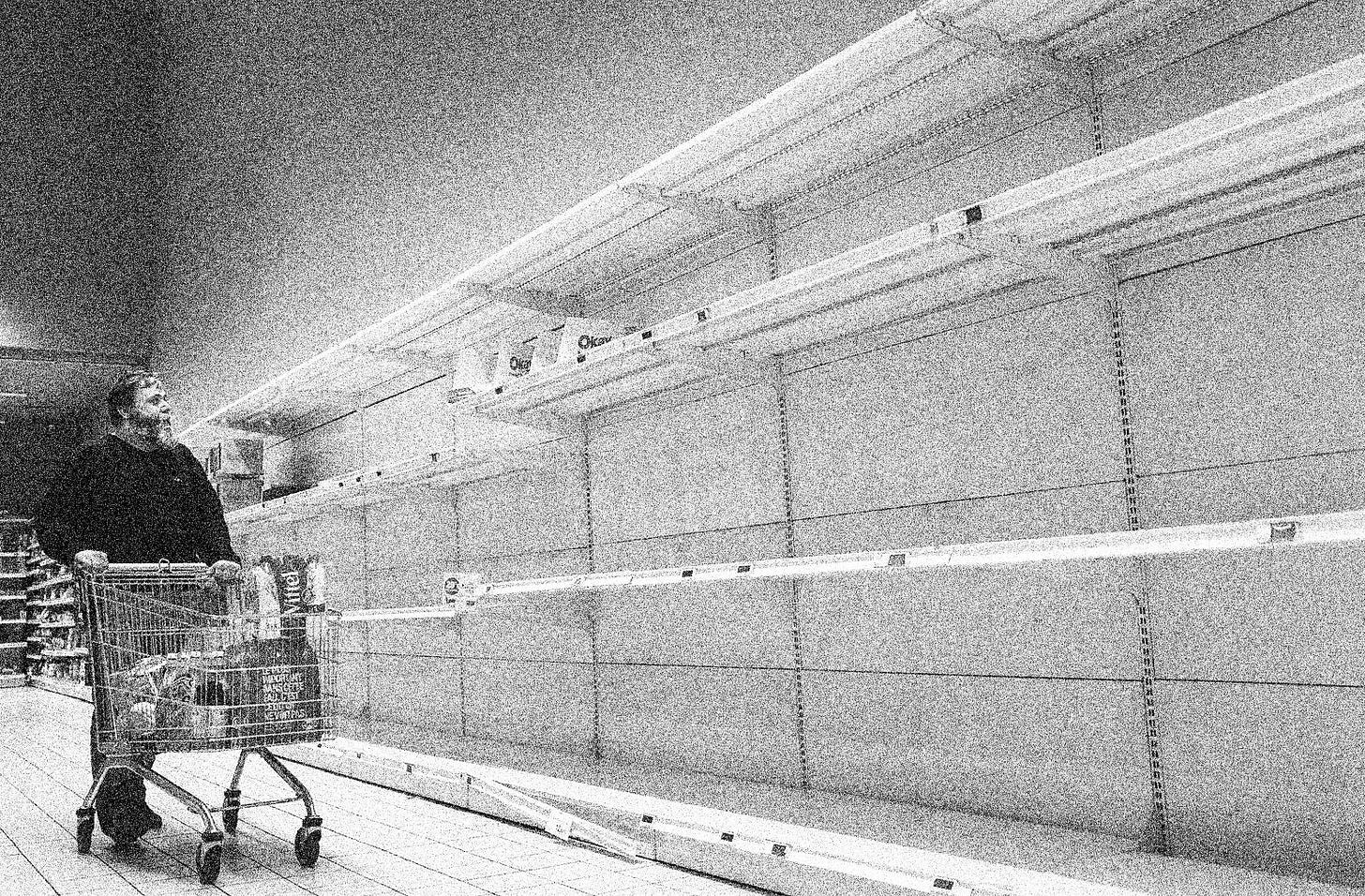

It used to be radical to claim that capitalism couldn’t produce enough stuff. Now it seems all too obvious that capitalism produces far too much. From mounting pollution to unfathomable stockpiles of weapons, our earth is practically collapsing under the growth of stuff that clearly serves no social good. It’s only a short jump from this fact to the com…