What was Psychiatric Deinstitutionalization?

An interview with sociologist and historian of psychiatry Andrew Scull about the history and legacy of psychiatric deinstitutionalization.

Damage Magazine: What did care for the mentally ill look like before the rise of the asylums?

Andrew Scull: Well, that's going back a very long way. The asylum becomes the primary response to serious forms of mental illness beginning in the early nineteenth century, and as far as America's concerned, 1820’s, '30s, '40s. Before that, it depends a bit on where you are geographically. If you're talking about the United States, as far as we know, virtually everything revolved around the family. It was the family's responsibility to somehow cope, as best they could, with a deranged member. If there were no family members, then communities often intervened in an ad hoc fashion, often simply by locking them up in some informal fashion, as best they could, particularly if somebody were considered to be a dangerous person because of their mental distress.

That had been the case for many centuries in England. Beginning, even in the late seventeenth century, we see a handful of small, private madhouses operated for profit beginning to emerge, and a few charity asylums, the most famous of which dates all the way back into the twelfth century. That's Bethlehem Hospital, or Bedlam, as it was called. But we're talking about a very, very tiny fraction of people institutionalized in such places. At the end of the eighteenth century in England, there were maybe a couple thousand in such institutions, and a very wide range of experiences for those who were confined in them.

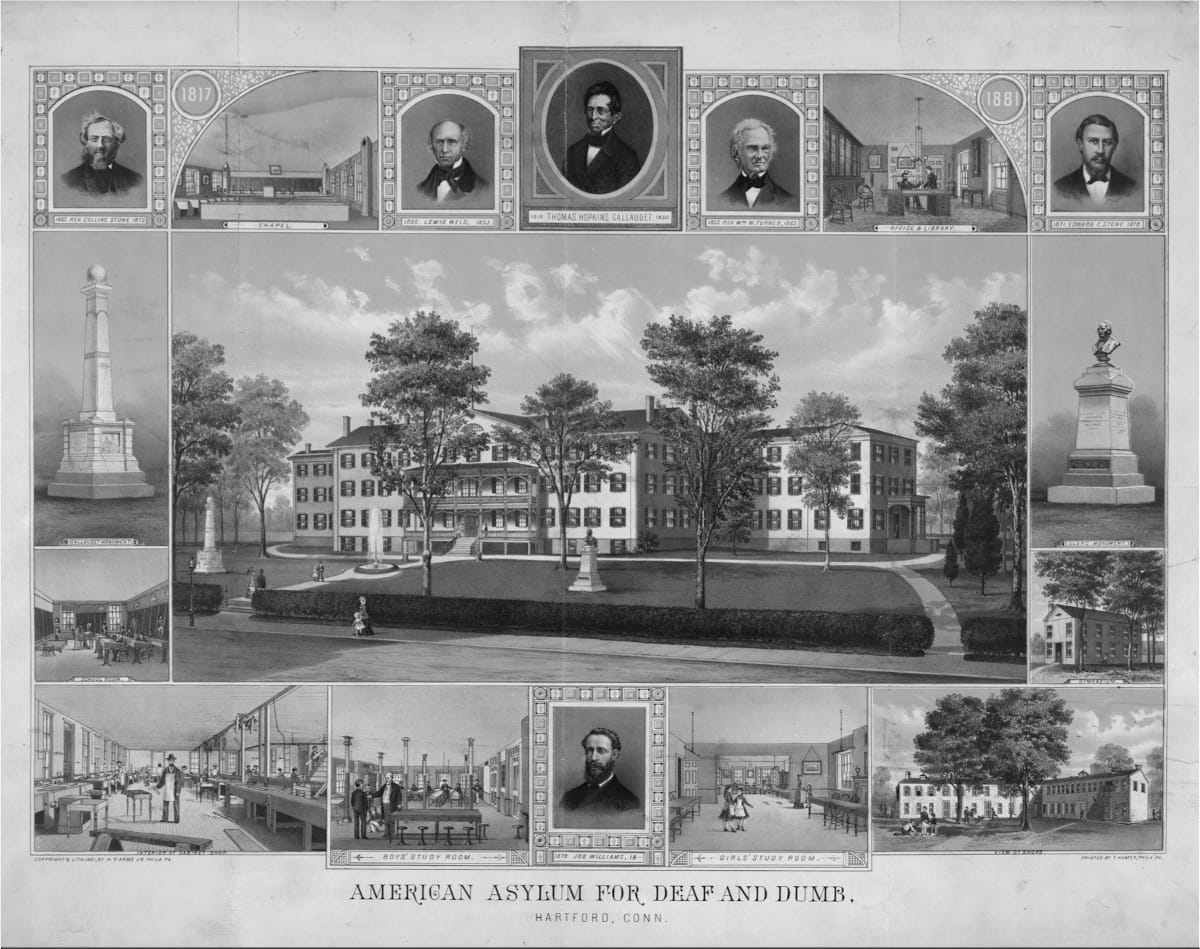

The asylum is essentially a nineteenth-century creation. It became apparent that mental illness bankrupts people, that it makes them unable to provide for themselves, and because its victims are incapable of work, mental illness tends to crash household resources. So whereas medical care remains a commodity you have to pay for, increasingly in the nineteenth century, on a state by state basis in the United States, state asylums begin to emerge, paid for by the public. The lunatics, as they're then called, are confined largely at public expense, sometimes with subventions from the family if they have some money.

There is a small private sector that emerges in the United States and some of those hospitals persist all the way down to today. The McLean Hospital, in the Boston area, being one example. Others of them have changed location, or names. There was one called the Hartford Retreat, set up in Connecticut at a time when Hartford was a very affluent part of the country. That, now, is called the Institute of Living—an attempt, I think, to disguise what it's about. Unfortunately, its address is “Asylum Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut,” so it doesn't quite work.

So, asylums begin in America. Once the notion has arisen that asylums might be able to cure mental illness, in a time of extreme optimism about what they can do, the main driving force spreading that notion and getting states to sign on to the expense of building these places is a woman named Dorothea Dix from Boston. At a time when women had no vote and were largely excluded from public life, this single, moral entrepreneur travels the length and breadth of the United States persuading good ol’ boy politicians that they need to spend money on this project.

Thanks to Dix and others, asylums grow rapidly in both number and size. So by the end of the nineteenth century, asylums of 1000, 5000, and even, in the case of Milledgeville, 10 or 12,000 patients, had arrived on the scene. From then forward until at least the middle of the twentieth century, the major official response to serious mental illness is to put people in institutions. Not everybody ends up there, of course, but we're talking by 1950, half a million people, on any given day, in state and county mental hospitals across the US.

DM: In accounting for the rise of the asylums you talk about moral entrepreneurs like Dix, and about the economic burden of caring for the mentally ill on individual families, but were there broader political economic shifts that gave rise to what you call the “empire of asylumdom”?

AS: Yes. I think there were. Geographical mobility, urbanization, the separation of work from the home, all of these things multiplied problems for families. They often broke extended families down. They made it much more difficult for families to use traditional expedience to cope with people at home.

This is also a time when states, including the United States, start to invest in institutional solutions to all sorts of social problems: poverty in the form of workhouses, prisons in the form of penitentiaries, and much more elaborate prison regimes, even institutions for other kinds of people who are seen as socially problematic, or have problems that are hard to cope with—institutions for the blind, institutions for juvenile delinquents. The nineteenth century sees the rise of that whole enterprise. Of course, it's dependent upon the expanding power of the state, its ability to tax, but also on an ideological shift that sees these kinds of institutions as a solution to the problems of crime, mental illness, or poverty.

DM: What was the “moral treatment”? Where did it come from? And how did it influence asylum practices?

AS: In the late eighteenth century, in France, in England, in Italy to some degree, you have the rise of institutions trying to cope with people rather than keep them scattered among families. In those institutions, there's very little in the way of external control, at that time. There's a wide variety of things tried out. Almost by trial and error, some of the people managing mental patients develop a technique, which is known in France as traitement moral and in England as moral treatment.

Fundamental to this moral treatment approach, to its early successes, and to the optimism that it generates is the idea that human nature is malleable; that it's a product of environmental influences, that people can be coaxed back to sanity, or to the common sense that the rest of us think we share. That's done partly through the physical environment. This is why asylums are so central, early on, because in those institutions you can control things much more, but you also create a moral architecture. Moral treatment wants to do away with straightforward imprisonment as much as possible, to substitute for it incentives for people to behave themselves, coax them into reasserting their own powers of self-control over their behavior. Reward them when they do that, and penalize them, but not through harsh punishments, when they don't.

So all aspects of the environment are terribly important. You locate asylums in pleasant surroundings. You disguise the fact there are bars on the windows by painting them to look as though they're the usual wood dividers of windows. You allow people who behave themselves to take tea with you in the English ritual, at four o’clock in the afternoon. You encourage them to take pets because that brings them out of themselves.

To be clear, the point was not to reason with people about their madness. Moral treatment proponents are very clear that you can't do that. This is not Freudianism. This is not getting people to talk about their mind, it's getting them to suppress it. When I say “suppress,” that highlights the other side of moral treatment, which is that it becomes a series of techniques for controlling people's behavior and evolves eventually into a ward system, which the Canadian American sociologist, Erving Goffman, analyzes in the mid-twentieth century.

So if you act out, if you behave badly, you move down the hierarchy to an ever more impoverished environment until you are with people who are demented and otherwise incapable of normal communication. The basic message is, “If you behave yourself, we'll start to improve your surroundings. If you want to see the outside world at all, you better control yourself.” Eventually it becomes this organized routine, this set of rules, that really is no longer the kind of individualized moral therapy that it started out being in the early nineteenth century. Over time, patients lose their autonomy, they lose their ability to make choices in their lives. From the point of view of those running the institutions, that makes it easier for them to cope. But from the patient's point of view, it kind of exacerbates whatever pathology already exists.

DM: You have written in Madness in Civilization: "Few would dispute the claim that asylums operated along moral treatment lines provided a more humane environment than the worst of the traditional madhouses. Well, actually the French philosopher Michel Foucault and his followers would." What was Foucault's characterization, and why is it wrong?

AS: I have a lot of quarrels with Foucault as a historian, which he really wasn't. He was a philosopher and social thinker. I would say I see a more complicated, more nuanced picture than Foucault does. There was a Roman god named Janus, who had a face facing forward and a face facing backward, two-sided. Foucault, for me, is too one-sided. He sees the defects, but fails to acknowledge anything on the other side of the equation. It's all oppressive. It's all hopeless. I'm, by no means, a naive optimist about the situation. I don’t subscribe to the meliorist notion that these asylums were wonderful places. They clearly were not, in many, many ways, particularly as time passed. The thing they did provide was a roof over people's heads, food (which was often pretty awful, but nonetheless was food), clothing, and some attempts at social stimulation, for at least a fraction of the patients.

But it’s certainly true that asylums did become awful places over time. When patients were locked away like this, out of sight and out of mind, there was a lot of hidden violence. You were asking ill-educated, ill-trained attendants, who were the people most of the patients saw most of the time, to turn the other cheek when patients exhibited no gratitude, when they were violent, when they would throw feces at you. So, the subculture of a certain degree of violence was certainly there, no matter how hard anybody tried to eliminate it.

Patients also came increasingly to be blamed for their own status. They were seen as lacking some of the central qualities of humanness, if you like. When you look at the writings of alienists, or psychiatrists, as they came to call themselves at the end of the nineteenth century, they start talking about these people as defective, as people who have the sort of pedigree of mongrel dogs, as if they'd be wrapped up in a sack and thrown into a pond and drowned. So there's this very harsh language that then mutates into an untrammeled willingness to experiment on patients, in ways that in retrospect look quite horrific. It's the isolation of these institutions, and the stigma attached to mental illness, and the powerlessness of the patients, that permits this kind of thing to happen over and over again.

By the last third of the nineteenth century, mental hospitals had lost their luster. They had lost much of their claim to be therapeutic institutions. In part, it was an over-exaggeration, but they're seen as places where once you enter, the only way you're going to come out is in a pine box. Now, that's not actually true. Even in the depths of late nineteenth-century pessimism, perhaps a third or a little more of each year's intake would leave within a year. The thing is, if you didn't leave within a year to eighteen months, you were unlikely to leave, except when you were dead.

So, the institution's reputation becomes one of a kind of warehouse, if you like. Then in the early twentieth century, faced with that reputation, we see the emergence of attempts to break with that pessimism. These often move social policy in directions that, looking back, seem rather pernicious. So we have, for example, the connections of mental illness to eugenics, to the fact that it appears to be to some degree a hereditary disorder, as it still is thought to be. This is when we see the rise of involuntary sterilization and other interventions increasingly directed at the body. Attempts to shock people back into sanity, attempts to operate on their brains, to operate on other body parts, assuming that infections elsewhere in the body are poisoning the brain. In a pre-antibiotic era, you've got to rip out the bits that are infected, whether it be teeth, tonsils, stomachs, or colons. So, there are a lot of interventions of that sort: insulin coma therapy, ECT, lobotomy, and a lot more besides.

The mentally ill become shut up in a double sense. They're obviously locked away, but they also lose all their civil rights, and their voices are not listened to. They're seen as the product of their mental illness, and therefore, to be disregarded.

DM: Aside from the bad reputation that the asylums had gained, and the obvious inhumanity of the new methods adopted in the twentieth century, what else drove deinstitutionalization?

AS: The nineteenth century solution to the problems of criminality, poverty, and mental illness was to build big institutions, and that persisted well into the middle of the twentieth century. In New York state in 1950, if you looked at the state budget, 30% of it went to New York state's mental hospitals. They were a huge expense. There were conferences of governors in the late '40s and '50s, where they all asked, “What are we going to do? This is a huge problem.”

It was becoming more expensive, and thus a more pressing problem, for a couple of reasons. First of all, many of these institutions had been built 50, 100 years before and were decaying, particularly because they hadn't been invested in during both the Great Depression and World War II. Also, after World War II, union strength was growing. The attendants in the mental hospitals were unionizing. Work weeks had been 80 or 90 hours a week, and you lived on the premises. If you were an employee, you were trapped every bit as much as the patients. But now work weeks became 50 or 55 hours. That added to the expense of things.

There were also a lot of journalistic exposés of the mental hospital, later supplemented by the work of sociologists and anthropologists. Right after the war, a number of American journalists had been to the death camps in Germany and in what's now Poland. These returning journalists came back and visited America's mental hospitals and said, “These are America's death camps.” Due to the wartime shortages of food, attendants, and physicians, the hospitals were probably at the nadir of their status in those years. So Albert Deutsch, for example, was a journalist who'd written the first positive history of mental illness in America. He went around and produced a series of newspaper articles that were published in a book called The Shame of the States, where he explicitly compared what he'd seen to Belsen and Buchenwald. He wasn't alone in making that comparison.

So the reputation of the mental hospital was plummeting. It was in a very bad way. And yet, by 1955, on any given day, there were 500,000+ patients in these hospitals. Today, it’s less than 40,000, and our overall population has doubled. If we still institutionalized at the rate we did in the mid-'50s, there'd be over a million people in mental hospitals. Obviously, there aren't. A lot of them, however, are back in the jails. Dorothea Dix's campaign, in part, was to rescue mental patients who were confined in colonial and early national jails, and put them in reformed asylums. Now, the three largest institutions coping with the mentally ill in America are LA County Jail, Cook County Jail in Chicago, and Rikers Island in New York—all of them hellholes, without exception.

Of course, another side effect of the relatively abrupt discontinuation of the asylum system, and its non-replacement by anything substantial, is the homeless problem that confronts cities all across the United States, and particularly along the west coast.

DM: I want to provide a summary judgment of the asylum as an institution, and maybe you can say why it's wrong, or how it needs to be complicated. In brief, it’s an institution that started off with good intentions, under the belief that through the moral treatment people could be brought back to some kind of common sense. But over time, through an increasing emphasis on biological factors, they became more inhumane towards asylees' individual subjectivity, and at the same time institutions that, because of a lack of funding and being overstretched for the populations they were trying to deal with, just sort of fell into ruin. Is that a fair summary judgment of the asylums?

AS: I think it's not far off the mark. The early moral treatment institutions, when they began, had 50, 100, 120 patients. On Long Island, in the 1930s and '40s, you had institutions of 10, 15, 20,000, and any chance of individual attention to a patient simply vanished in the face of that kind of growth. It really, in part, was a function of simple mathematics. The early people thought they could cure 60, 70, 80% of patients in the asylums. In fact, maybe 40% would leave within the year, and then the rest would accumulate. Of course, some died. But over time, that inevitably created a situation where a larger and larger fraction of the whole were the chronic patients, and the new incomers, as a fraction of the whole, were less and less. That fed into the sense that these were places that didn't work and didn't cure. Once that perception spread, getting states to allocate substantial sums of money to keep these places running, at a reasonable level, became almost impossible.

The old phrase, "Out of sight, out of mind," really did apply. Patients were isolated. Except for the occasional journalists penetrating the scene, patients were largely invisible, and families lost hope. Connections to families, over time, attenuated and disappeared. So it really was a very difficult situation. That said, it's still important to recognize that even in fairly horrible conditions, patients had a roof over their head. They had some kind of food and some kind of clothing, and occasionally some social activities. It's, on the whole, a negative picture, but something where you have to bear in mind what the alternatives might've been and have proved to be, I think, since we've abandoned this system.

DM: There were two books that appeared in 1961. You've mentioned one already, Erving Goffman's Asylums, and then Thomas Szasz's The Myth of Mental Illness. Together they comprise something like a foundational critique of, not just the asylum as an institution, but the entire paradigm that informs the asylum as an institution. What do you make of these two works today? Were they accurate in their critiques? Were they overblown?

AS: Well, they were part of a broader movement in the '60s to criticize the psychiatric enterprise. They're rather different, I think. But overall, both of them contributed to delegitimizing the asylum system and did so by pointing out, often quite powerfully, its drawbacks and its defects, without really talking about what the alternatives were likely to be, if indeed they existed. Goffman tended to imply that the institution was the problem itself, that it tended to create the very behaviors that legitimized its existence in a kind of paradoxical fashion. It undermined patient autonomy. It created behaviors that to outsiders looked bizarre. But he had very little sense, other than talking about a certain “betrayal funnel,” about why it was that people ended up in these places. I think that was a huge failing in the book.

Szasz was... how to put it? He was an extreme libertarian in his politics. The Left often, in the '60s, adopted him, but they didn't realize what they were adopting. Szasz was a violent opponent of any state support for anything and considered that the mental hospitals were equivalent to concentration camps or prisons. He thought the people running them, his fellow psychiatrists, were acting in the interest of the state, not the patient. This condition called mental illness was, in his view, a myth because there was no physical cause of the condition. It wasn't an illness like pneumonia or tuberculosis. It was a socially constructed thing, a way of coping with people whose behavior we didn't like, and we couldn't abide. Under the guise of helping them, Szasz claimed, people were railroaded into these institutions that were nothing better than holding pens, prisons.

In the late 1960s, the purview of public interest law, which had emerged mainly around the Civil Rights Movement, began to expand. Some of those lawyers began to move from civil rights to talking about gay rights, to talking about the rights of mental patients, to talking about feminism and the rights of women. So they often seized upon these critiques of the mental hospital, and the critiques of the whole concept of mental illness, to launch a legal attack on these institutions.

There was a very famous case in Alabama, where George Wallace was the governor. It's called Wyatt v. Stickney. Stickney was the mental health commissioner for the state of Alabama. He actually invited the lawsuit because he wasn't getting any money out of Wallace to run his mental hospitals. He thought this lawsuit might help. So the lawsuit was launched, and it was heard by Judge Frank Johnson. He was a federal judge who'd been in law school with Wallace and loathed Wallace. He had testimony about what the minimum American psychiatric standards for a mental hospital would be, how many doctors per 100 patients, how many nurses, how many attendants, what the budget should be like, etc.

He decided the case and said to Wallace, “You have to provide these conditions.” Wallace's response was to discharge about 4,500 of the 5,000 patients in Alabama’s hospitals. Then for the 500 remaining, why, then he met the rules. So it was kind of perverse, but I think the lawyers bringing that suit, in part, actually wanted to get the patients out. What happened in the 1960s was this odd convergence of the Left and the Right in the critique of institutional psychiatry.

On the Left, they'd been convinced by the stories of the abuses in mental hospitals, of the travails of the patients, the loss of civil rights that confronted somebody who was declared insane. On the Right, for people like Szasz, these were examples of the state spending money it shouldn't have. I shared a lecture platform with him a couple of times. Once up in Canada, for example, two topics came up that kind of shocked the left-wing audience that assembled to hear him. This was a time when there were a series of murders in New York by somebody called the Son of Sam, who had gone around shooting courting couples in their cars and killing them. He'd finally been caught and pleaded insanity. The audience asked Szasz what he would do. He said, “Well, if he were my patient, I'd turn him into the police. Once he was convicted, I'd be happy to throw the switch and electrocute him.” There were gasps from the audience, but that was Szasz's position.

Then, the second thing that came up was about the safety net, social welfare, and social security, and Szasz said, “That should be abolished. People should provide for themselves, and if they can't, that's their tough luck.” So you had civil libertarians attacking the institution because of its failings. You had Szasz and people like Ronald Reagan, who became governor of California at the crucial moment, also wanting to abolish these places for a rather different reason. They didn't like the state intervention, but they also didn't like the amounts of money it was costing.

DM: How did deinstitutionalization proceed through different phases?

AS: Mental hospital populations peaked in 1955 in America. They begin to decline, somewhat slowly, for the first decade. Then from the late 1960s onwards, the pace of discharge picks up very sharply. Eventually, mental hospitals are largely emptied, and it becomes very hard to get into them. The psychiatrists often embrace the idea that this was all because of the advent of modern drug therapy, anti-psychotics, antidepressants. There's a lot of evidence that shows that's not the case, from a whole variety of perspectives. Some states adopted the drugs early, some adopted them later. Some state’s systems, like California’s, had hospitals that used drugs extensively, and others that didn't. When you look for patterns, you don't see what you'd expect to see. The hospitals that weren't using drugs were discharging patients more rapidly than the ones that were.

Yet when you look at the pattern of discharge, what you do see in the late 1960s is a massive discharge of old patients, patients over the age of 65. Then what you see from about 1972 forward is that that discharge pattern extends to younger patients. So what's going on at that point?

The first point, the '60s discharges among the elderly, that's Johnson's Great Society program. It's the passage of Medicare and Medicaid. Those old patients, if they're in the state hospitals or on the state budget, if they're discharged and go to nursing homes and board and care homes, they're on Uncle Sam's budget. So there's an incentive to move the patients out. You can see, as the elderly population in the mental hospitals goes down, the elderly population in the nursing homes goes up. It's a parallel development. What happens in 1972, under Richard Nixon of all people? Supplemental Security Income, in addition to social security, which provides a stipend to people who are disabled, including those who are mentally disabled.

You get the emergence of what I call a new trade in lunacy, another one of these things where entrepreneurs batten onto a new source of income. Problems emerge here because they're only lightly regulated, if they're regulated at all, these alternatives to the mental hospital. And the amount of profit you make is inversely proportional to how much you spend on the patient. So the patient brings in a check for $300. If you spend $290 of that on the patient, they probably get better living conditions, but you only make a tiny amount of money. If you spend $180 on them, well, you make a lot more money. So the logic of the marketplace dictated that these places did not provide great care. Then when we get into the 1990s, there’s welfare reform, which is one of Bill Clinton's great initiatives, and before that we have Reagan and Bush. So the safety net, which was never terribly strong, gets weakened and weakened and weakened. Now the states aren't providing, and the feds aren't providing, and you have a festering problem.

DM: What is needed for the care of the mentally ill today? Is it too much to say that we need to re-institutionalize in some way?

AS: Well, that's an enormously complicated question. What's happened over the last 50, 75 years is much more complicated than I've been able to talk about here. One of the great changes, of course, has been the psychopharmacological revolution, the arrival of drugs. Those have become American psychiatry's almost sole and singular remedy for serious mental illness. If you look at patterns, very few MD psychiatrists offer psychological counseling of any sort anymore. Yet when we look at mental illness, we see a problem that may well have not only biological roots, but also environmental, social, and psychological roots, and certainly environmental, social, and psychological impacts that have to be addressed.

So to the extent we narrow our focus to simply medication, and medication which is a band-aid rather than a cure anyway, we’re only addressing the symptoms of some fraction of patients. Half of all patients with depression aren't helped by antidepressants, and a large fraction of people with psychosis aren't helped, or only helped a bit, by these drugs, which have powerful side effects as well. So we've got to move away from biology as the sole solution to the problem.

We are also going to have to provide, but I don't think the political will is there to do it, some sheltered housing. This is going to be very controversial, but we also have to ask: to what degree are we going to involve compulsion in the system, and to what degree are the courts going to even allow that to happen? Both commitment statutes and court rulings about what you're allowed to do to somebody against their will have made it a very fraught legal situation to actually introduce an element of compulsion. It depends on whether you buy Szasz's view that this is all a myth, or you accept that there's a reality to psychotic illnesses, whether you accept the proposition that some people lose the ability to make appropriate choices about their lives. If you take the position that the state should not be able to compel somebody to get treatment, then I think you're facing a massive problem. But if you allow that compulsion, first of all, are you going to get it past the courts? Assuming you do, how are you going to guard against the kinds of abuses that existed back in the past? We would need to invest very substantial resources in this problem.

The difficulty is that this is a very unappealing population. Mental illness carries with it stigma. It always has. In every society I know, people recoil from it. Many people with serious mental illness are not going to get better. It's one thing to invest money where you're going to see a return, if you like, in the form of somebody being rescued. I don't want to imply that people never recover. Of course, that's not true. But with patients who were chronic in the asylum, patients who at best are going to improve a bit but are still going to be probably incapable of providing for much of their daily living, they're a burden. How do you persuade a public that has been sold on the idea that we're all individually responsible for ourselves that there is a collective obligation to provide a minimum level for all citizens? It's a hard sell. When you see budgets being cut over the last 70 years, programs for the mentally ill are always among the easiest to cut, and the hardest to increase.

Then the further problem is, "Do we have effective treatments?" The answer is, "Well, for some fraction of patients, yes. We have things that will make their lives significantly better." So, it's not a completely hopeless situation. But for many mental patients, what's going to happen to them with the best tools we have at hand? Drugs, cognitive behavioral therapy, whatever interventions we're talking about here. We can control their symptoms a bit. We can get them back, to some degree, in control over their lives. But being able to abolish their problems completely, we don't have that magic bullet. We simply don't possess it. I wish we did, but the honest answer to that situation is that we have, at the best, palliative measures.

Right now mayors across the United States, in New York, in Portland, in Seattle, in LA, in San Francisco, they’re all realizing they've got a huge problem on their hands. The public, which is increasingly seeing how having our streets full of people, some of whom are seriously mentally ill, is damaging the very social fabric of daily life. So there's some pressure on the other side. Whether that will result in punitive responses, or more caring and effective responses, remains to be seen.

■

Andrew Scull is Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Science Studies at the University of California-San Diego and author of Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity, from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine.