Going Beyond the Politics of Institutional Racism

“Institutional racism” was a flawed framework for understanding inequality when it was first introduced by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in 1967. Today, as a synonym for “racial disparities,” it is even more obfuscating.

“Institutional racism” is now mainstream. Or at least talking about it is. What was once a term heard mostly in academic lecture halls is now commonly uttered by anyone with a daytime talk show or social media account. While the phrase seems to add intellectual heft to an argument, in reality it usually acts as a placeholder for a variety of interpretations that obfuscate the root causes of contemporary racial inequality, while also lending credibility to neoliberal policy agendas.

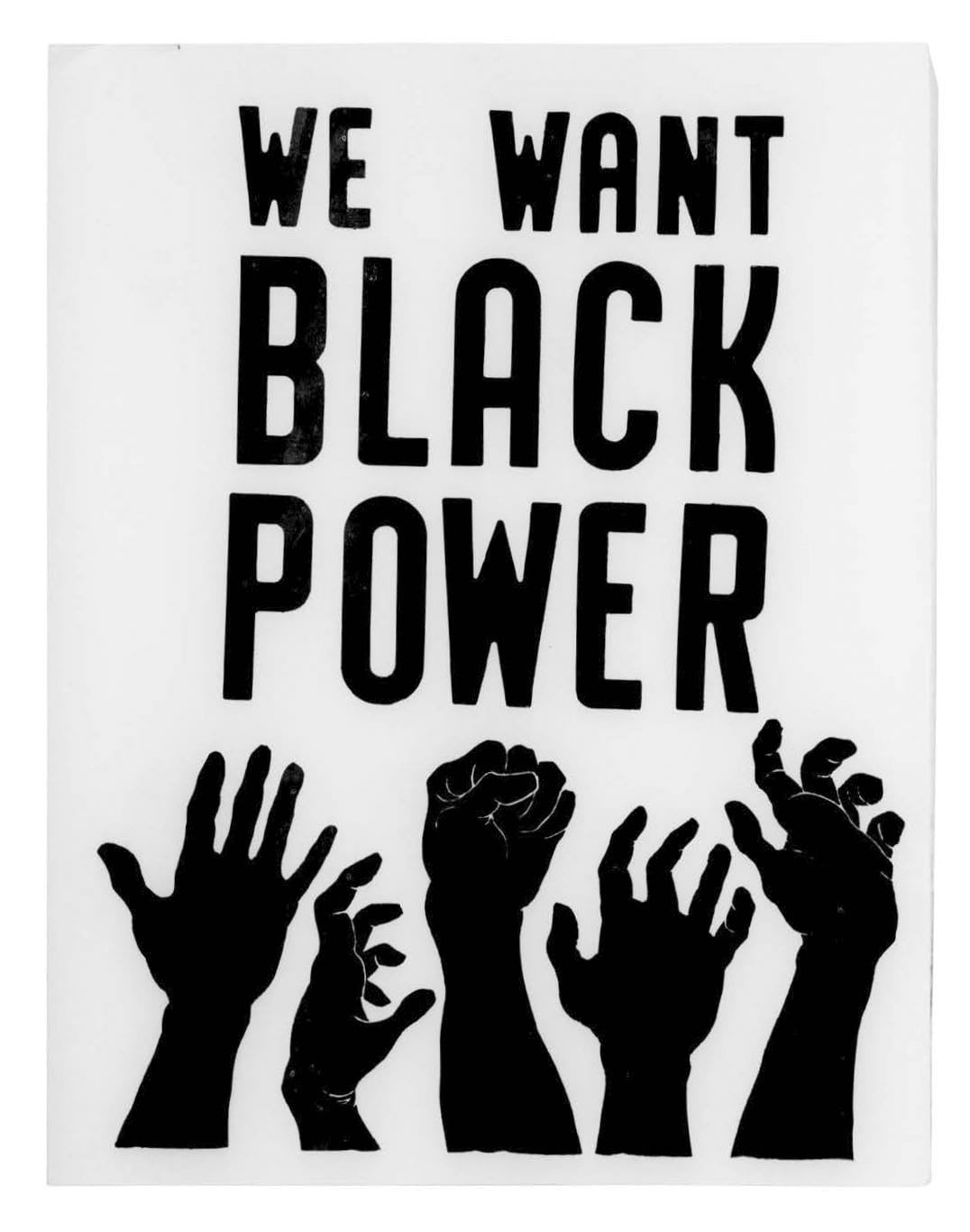

Part of the issue is the lack of clarity on what the term even means today. What are the roots of the institutional racism framework, and how have the conditions that produce racial inequalities changed over time? One of the earliest and clearest explanations of institutional racism came from Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely Carmichael and political scientist Charles V. Hamilton in their seminal 1967 work, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation.

Black Power cannot be separated from its context. Written after a feverish period of civil rights activity culminating in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the authors sought to analyze the enduring forms of racism that the movement still seemed unable to address. They distinguished institutional racism from “overt acts by individuals, which cause death, injury, or the violent destruction of property.”

Institutional racism was “less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing the acts.” Instead of locating its cause in the individual, Carmichael and Hamilton claimed it “originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society, and thus receives far less public condemnation than the first type.”

This analysis seems to align perfectly with a Left critique that emphasizes structural and systemic issues rather than the choices of individual people. This framework stresses material concerns such as jobs, housing and education.

They further elaborate, “When white terrorists bomb a black church and kill five black children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of society. But when in that same city—Birmingham, Alabama—five hundred black babies die each year because of the lack of proper food, shelter and medical facilities… that is a function of institutional racism.”

Carmichael and Hamilton use the term “white power structure” to describe the complex web of domination that upholds and reproduces institutional racism. Again, to their credit, they attempt to explain how this power structure operates in concrete material terms. The “white landlords who come only to collect exorbitant rents and fail to make necessary repairs,” the white cop who will “brutally manhandle a black drunkard in a doorway, and at the same time accept a pay-off from one of the agents of the white-controlled rackets,” and the city department that oversees “the streets in the ghetto lined with uncollected garbage” are all examples of this white power structure in action.

While this analysis of racial inequality is much more grounded in material reality than a lot of the discussion in our time, there were fundamental problems with this framework even in their time. Labeling persistent social inequalities as expressions of an “institutional racism” is a misdiagnosis of what are structural features of capitalism, and doing so produces an incomplete picture of the other groups in society who may be experiencing similar problems.

This may seem like a quibble over terminology, but it’s of fundamental importance in determining the strategies and programs for combating racial inequality. While the language of institutional racism sounds like it articulates a systemic approach, it lends itself to a more limited policy agenda that focuses on effects rather than causes, and prioritizes (ironically) individualistic efforts as solutions.

These dynamics come out clearly when Carmichael and Hamilton discuss various programs of action. Their first call to arms focuses on an appreciation of black culture: as they write, “Our basic need is to reclaim our history and our identity from what must be called cultural terrorism, from the depredation of self-justifying white guilt.” While cultural pride is not necessarily a bad thing in itself, this type of inward-looking redemption evades the work of challenging and reforming institutions. Black cultural expression can flower while the jobs, education, housing, and healthcare for the majority of black working people continue to decline.

On the issue of education, the authors advocate for local black community control of schools. While more parental input and more black teachers are also not bad things, this project misses the institutional dynamics that produce educational inequality. Black parents can control the School District of Philadelphia, but without the ability to attain more resources from the state and federal government, the persistent problems of dilapidated buildings, overcrowding, teacher turnover, lack of support staff, and dwindling after school programs will continue.

Black Power attempts to tackle the question of political institutions as well, but the prescriptions here are even murkier. They declare that “Black people will choose their own leaders and hold those leaders responsible to them,” but the leaders will be different from the black politicians already in place because they will embody “the power… of a community, and emanate from there.”

This analysis suffers from a failure to appreciate the way local political institutions are impacted by national economic factors. Many of the urban black mayors and city council members who took office throughout the late 1960’s and 1970’s came out of local struggles for civil rights and could be said broadly to represent the aspirations of the black voters who elected them. However, they came to power just as manufacturing jobs were deserting urban centers and federal revenue for cities was drying up. As political scientist Cedric Johnson says of this political class in his recent book, After Black Lives Matter, “Governing through the compounded fiscal and social crises of the seventies and eighties meant making difficult choices with unforeseen and often regrettable consequences.”

When analyzing the theory of institutional racism today, we first must look at what has changed and what has not since Black Power was published in 1967. Certainly racial inequalities persist in all the major social welfare indicators, and the black unemployment rate continues to be double that of white workers. However, this reality can mask the other ways racial politics has profoundly changed over the last sixty years.

The major legislative gains of the civil rights movement created the basis for the emergence and reproduction of an entrenched black political class in urban black population centers throughout the country. It also opened up important educational and employment opportunities for a more middle-class stratum of black professionals, creating a class divide that today is bigger among blacks than whites.

The important progress made by civil rights legislation came at the dawn of an era of profound structural economic changes that would render these gains increasingly hollow. Anti-discrimination laws could not meaningfully counter the devastating effects of developments like the mechanization of Southern agriculture, automation, or the flight of unionized industry to the (mostly white) suburbs. This reality was summed up by A. Philip Randolph at the 1963 March on Washington: “Yes, we want a Fair Employment Practice Act, but what good will it do if profit-generated automation destroys the jobs of millions of workers, black and white?”

Today, the term institutional racism is often used as a shorthand or synonym for racial disparities. While these disparities are indeed real, the deployment of institutional racism as a rhetorical framework does not illuminate the causal factors of these inequalities in the modern neoliberal era, and doesn’t adequately take into account the changes in black social and political life that have taken place since the civil rights movement.

The focus of institutional racism discourse today is still the institutions of education, housing, etc. But the emphasis is on eliminating disparities within these institutions rather than changing or replacing them. This all-consuming disparities drum-beat produces policy ideas very much in line with the neoliberal order. Instead of making higher education free and accessible to all, the aim becomes ensuring the proportionate number of minority students are enrolled. Instead of fighting to turn bad, low-paying jobs into good jobs, the idea is to make sure these bad jobs are held by the correct proportion of black people.

Perhaps the real tell that the institutional racism framework is often at odds with an egalitarian agenda is how its proponents react when confronted with a real-life movement that challenges the major institutions in society. The Bernie Sanders campaigns of 2016 and 2020 represented such a movement. His policy platform, if realized, would’ve nearly revolutionized the education, healthcare, housing, and employment systems as they currently exist. Though framed as universal, these policies would have done more to combat racial inequality than anything in the country’s history.

But more often than not, those who use the rhetoric of institutional racism in academic conferences or on social media met the Sanders campaigns with deep skepticism, if not downright hostility. If a small decrease in a local police budget or the growth of small black business can be deemed more consequential for black lives than free healthcare for all, then perhaps there is nothing institutional at all about the theory of institutional racism.

In Black Power, Carmichael and Hamilton lament the fact that during the civil rights movement, the “objective day-to-day condition worsened” for most ordinary black people. Here these black nationalists were in agreement with socialists like Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, who consistently pointed out that civil rights laws did not touch the lives of black people in the urban north.

But Rustin and Randolph recognized that these worsening conditions were not caused by racism alone and could not be addressed by focusing on race alone. They also saw that what black people were experiencing was the worst edge of a broader assault on all working people. From this perspective, and during the same time period that Black Power was being written, they launched the Freedom Budget for All Americans to win national healthcare, universal housing, full employment, expanded social security, and more.

While this effort clearly failed, it should serve as a guidepost for how we can truly challenge institutional inequalities in all areas of social life.

■

Paul Prescod is a contributing editor for Jacobin Magazine and a labor organizer.