Odd Man Out

The Odd Fellows were once the largest fraternal organization in the United States. Much like other such associations, their decline has been rapid and devastating, but remarkably, some still bear great faith in the future of Odd Fellowship.

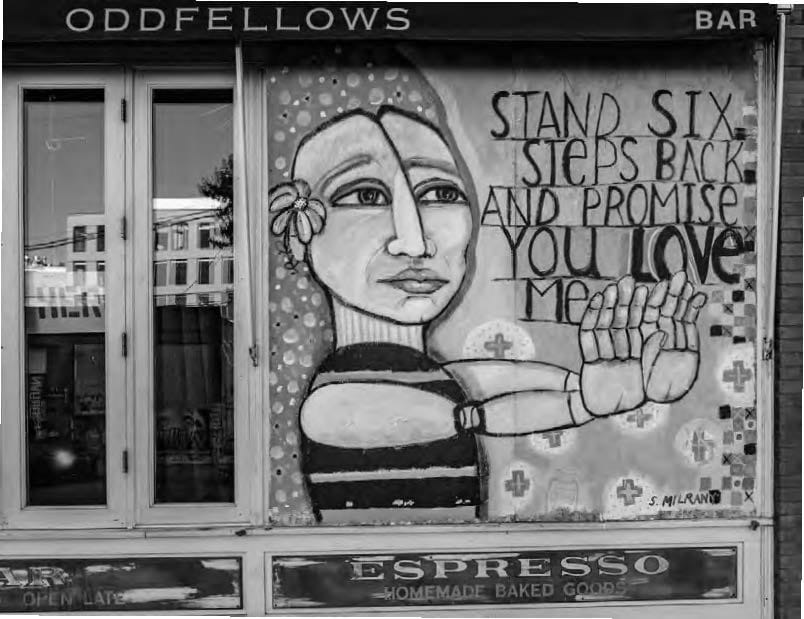

Oddfellows Café + Bar is a popular brunch spot in Seattle where you can get a salmon benedict for $29 ($34 with avocado). For seating, it has pews, procured from the nearby St. Joseph Church. Oddfellows’ founder and previous owner, Linda Derschang, bought them for their “history”—not their actual history but for “evoking the feeling” of history. Oddfellows was also part of the area occupied in the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or CHAZ. During this period, a mural hung in front that read: “STAND SIX STEPS BACK AND PROMISE YOU LOVE ME.”

Oddfellows employees believe that the place is haunted by ghosts. They’ve seen them and heard them, or at least they’ve told their boss Derschang (who has a penchant for the supernatural) that they have. Designed to conjure an air of history without any particular content, plopped at the intersection of wealth and anarchy, it’s no great surprise that specters might inhabit this dizzying array of cultural contradictions. And we don’t need to go very far to find them. They’re right there in the name.

The restaurant shares that name with the building it occupies, the Odd Fellows Building, constructed in 1908 by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. The Order owned the building until 1995, when it was discovered that a neo-Nazi separatist movement had infiltrated the Lodge. The national organization quickly disbanded the group and sold the building to a local real estate investor, who maintained the space as a home to many arts organizations in a self-consciously bohemian neighborhood. In 2007, the building was sold again, and most artists were forced to leave. The dance studio Century Ballroom is all that remains of a once vibrant arts space; now its occupants sell running shoes, sustainable apparel, and protective cases for laptops and tablets. This transformation represents in condensed form the broader “Amazon-ification” of a once sleepy Pacific Northwest hub.

In the eighteenth century, the Odd Fellows were “friendly societies” in Britain that got together to socialize and help one another out; “mutual aid networks” might be a more contemporary designation. As it is today, this was considered “odd” at the time, and it’s appropriate that the organization’s titular “oddness,” in one theory, refers specifically to the audacity of associational life that was budding at the time. In 1843, American Odd Fellows lodges separated themselves officially from the British, forming the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. It’s counted amongst its members Ulysses S. Grant, Wyatt Earp, William Jennings Bryan, Charlie Chaplin, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1851, the IOOF was the first fraternal organization in the country to make a place for women through the creation of the “Beautiful Rebekah Degree,” though it took another 150 years for the organization to become co-ed. Today both men and women can be Odd Fellows, and both can also attain the degree of Rebekah.

During the so-called “Golden Age of Fraternalism” (the late nineteenth/early twentieth century), the IOOF was the largest fraternal group in the country, even larger than the Freemasons. It also bore a more working-class membership than did the more elite Masons. No surprise then that the Great Depression and subsequent New Deal hit the Odd Fellows hard: with members struggling to keep up with dues and the state increasingly taking on the function of social provisioning, the IOOF began a steady decline. Its membership has since dropped by roughly 40-50% every decade as a proportion of the total population; today it has just more than 25,000 members.

The IOOF is one of the more dramatic examples of the decline of associational life in the United States more generally. In the 1990s, Theda Skocpol and researchers at Harvard’s Civic Engagement Project made a list of all US membership associations that enrolled at least one percent of American men, women, or both in 1955. Virtually all of these organizations had experienced severe decline by 1995, most notably the AFL-CIO, and with dire consequences for American politics. Skocpol offers a helpful example of how this transformation in associational life in the United States plays out in the political sphere:

Imagine for a moment what might have happened if the GI Bill of 1944 had been debated and legislated in a civic world configured more like the one that prevailed during the 1993-94 debates about the proposal for national health insurance put forward by the first administration of President Bill Clinton…. In the actual civic circumstances of the 1940s, elites did not keep control of public debates or legislative initiatives. Instead, a vast voluntary membership federation, the American Legion, stepped in and drafted a bill to guarantee every one of the returning veterans up to four years of post-high-school education, along with family and employment benefits, business loans, and home mortgages. Not only did the Legion draft one of the most generous pieces of social legislation in American history; in addition, thousands of local Legion posts and dozens of state organizations mounted a massive public education and lobbying campaign to ensure that even conservative congressional representatives would vote for the new legislation.

Half a century later, the 1990s health security episode played out in a transformed civic universe dominated by advocacy groups, pollsters, and big-money media campaigns. Top-heavy advocacy groups did not mobilize mass support for a sensible reform plan. Hundreds of business and professional groups influenced the Clinton administration’s complex policy schemes and then used a combination of congressional lobbying and media campaigns to block new legislation. The American people, especially low-income families, ended up without the desired extension of health coverage. American citizens recoiled in disgust at the expense and gridlock of the whole episode.

A polity without membership-based civic organizations is one insulated from popular pressure. A whole representative infrastructure once existed to tie individual and local concerns to state and national ones; today nonprofits and foundations provide a “protective layer” (to use political scientist Joan Roelofs’ term) insulating the DC blob from the frustrated masses.

Fraternal Organizations in the United States with Membership Totalling at Least 1% of Men (18+) in 1955 (not including Freemason suborganizations)

Fraternal Organization

1955 Membership

1995 Membership

2020 Membership

% Change

% Change as a Proportion of the Total Population of 18+ Men**

Ancient and Accepted Free Masons

4m

2.3m

1.02m

-75%

-89%

Fraternal Order of Eagles

760k

776k

800k

+5%

-55%

Loyal Order of Moose

844k

1.26m

650k

-23%

-68%

Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks

1.15m

1.36m

750k

-35%

-73%

Knights of Columbus

800k

1.26m

1.9m (1.4m*)

+138% (+75%*)

-0.5% (-26%*)

Independent Order of Odd Fellows

543k

97k

25.7k

-95%

-98%

*The Knights of Columbus appears at first to be doing much better than the other organizations listed here, but they were recently found to be “massively inflating” their membership numbers to bolster their insurance company.

**In 1955, all of these organizations exclusively accepted men. The Fraternal Order of Eagles began accepting women in 1998; The Independent Order of Odd Fellows in 2001; The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks in 2005; and The Loyal Order of Moose only in 2021. However, many of these organizations have long maintained women’s auxiliaries.

In the case of fraternal organizations, however, an even more basic social concern is at work—one once urgently raised in the work of political scientist Robert Putnam but now so taken for granted as to appear uninteresting. Temples, Aeries, and Halls used to be places where people gathered, where communal life was centered, and where you could go if you were traveling or recently relocated and find someone to have a beer with. In the post-war era, they were all of these things for men (and their families secondarily) and for certain groups of people rather than others, but there’s broad recognition in all of these organizations today that any hint of the old forms of discrimination and hierarchy ought to be eliminated. The exclusions are mostly gone, but then there’s much less to be excluded from.

Run DMC

Rick Boyles, past Grand Master of the California Grand Lodge of Odd Fellows (essentially, president of the state federation), is particularly concerned with continuing membership decline. For years, he has been closely tallying the Order’s membership numbers and, in 2010, he helped start Dedicated Members for Change (DMC), an internal organization attempting to revive Odd Fellowship. Despite the hope for transformation embodied in this small group, his diagnosis is near terminal: “The decline in numbers may be beyond resolution at a certain point, and we are quickly approaching that level.”

The key driver of membership loss is unsurprising: “It’s the mortality rate,” said Boyles, “and the fact that fraternal groups in general attract the elderly.” He also pointed to some inner turmoil between the national organization (the Sovereign Grand Lodge), state/regional federations (Grand Lodges), and individual Lodges, and the way in which some increasingly miniscule Lodges resist needed modernization: “People are protecting their little areas.” Dave Rosenberg, who started DMC with Boyles, agrees about the problem of little fiefdoms: “People become comfortable in their little niche, and bringing in a new member changes the status quo. Some of the old timers don’t like that.”

Unlike Boyles, however, Rosenberg doesn’t like pointing to the facts of life to explain Odd Fellowship decline: “We’re not diminishing because of mortality,” he told me. “It’s lack of involvement. It’s laziness. It’s complacency.” Like Boyles, Rosenberg is a past Grand Master and also past Noble Grand of the Davis, CA lodge, where he first became highly invested in the Order. As mayor of Davis from 1986-1988 and again from 1994-1996, he noticed a decrepit old Odd Fellows building taking up valuable downtown space. Quickly upon joining the lodge, he began making sweeping changes to both the lodge and the temple (Odd Fellows groups are called lodges, Odd Fellows buildings are called temples). The temple was modernized: a neon “IOOF” sign was shipped in from a temple out east, an elevator was installed, and long overdue repairs were undertaken. The culture of the lodge was also transformed: it started a classic film festival, a knitting group, a beer making group, and a now annual Zombie Bike Parade. Committees dedicated to individual member interests proliferated. “If members want to do something, we say go for it.” When Rosenberg joined in 2004, the Davis lodge had 25 members; today it has 400, and 70 some committees.

DMC holds up the example of Davis as pointing the way to Odd Fellowship rejuvenation. Rosenberg’s ironclad faith in the possibility of communal life in an increasingly atomized world is indeed rather exemplary. For him, it’s not decline; it’s a lack of effort. For all the invocations of “community” today, few people are concretely building it like Rosenberg has. He has devoted himself wholly to rehabilitating an old building in downtown Davis in order to cater to individual interests as expressed through committee structures, and even more remarkably, he’s had success at doing so. Which is all, well, odd.

The Archaic Stuff

DMC is about breaking down barriers, and that includes the traditional religious ones. Peter Sellers, another prominent DMC member from San Francisco, is vocal about wanting a non-sectarian, pluralist Odd Fellows that does not make faith a precondition to entry. It is typical that applicants are asked to profess faith in a Supreme Being, and the question of whether or not to allow in Odd Fellows who are explicitly atheistic or agnostic is probably the most contentious issue within the Order at present. For Sellers, the choice is clear: “In my Lodge, we don’t bar you if you’re an atheist.” He joined to be in a fraternal organization, not a church: “I didn’t come to say prayers.” While treading lightly around what they all admit is a “heated topic,” Rosenberg and Boyles seem to share a desire to prioritize the social life of the Odd Fellows over traditional adherence to the faith requirement and degree rituals.

Michael Douglas disagrees. “Taking all the archaic stuff out of it and trying to be a normal community group, that’s slitting our own throats.” Like DMC members, Douglas thinks “the fraternal manner of organization has legs to move into the future,” but also believes that the old rituals and structures are part of the Order’s strength. “The rituals and the lessons are timeless. [They provide] an education in a sustainable society.”

Douglas is an interfaith minister and has worked for a few different Sufi orders. He first found out about the Odd Fellows performing a Sufi ritual in their space. He fell in love with the building and signed up to be a member about 15 years ago. He’s one of about 50 members in the Ballard Odd Fellows, the last remaining Lodge in Seattle after the Odd Fellows building in Capitol Hill was sold.

Douglas is not against modernization: “We have to rewrite the rituals every so often to keep up with things.” But he is also highly committed to the older ways and doesn’t find much alienating about the requirement to believe in a “Supreme Being”: “We don’t care how you define it. We’ve had Buddhist priests who say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s Buddha-nature, or that’s dharmakaya.’ We ask the question because if you can’t say yes, you’re just not gonna be able to swing with all the nineteenth-century deist stuff. If you can’t swing with a theological metaphor, it’s not gonna be positive.”

The rituals, to be clear, aren’t very demanding. It used to be that many Lodges put you through the ringer: naked, blindfolded, flaming you with torches… but not anymore. After a simple initiatory ritual, one goes through three degree ceremonies on the way to becoming a full-fledged Odd Fellow. These degrees correspond with the three core values of Odd Fellowship: Friendship, Love, and Truth (it’s common to see F-L-T on Odd Fellow signage). Unlike the Masons, one doesn’t have to study for these degrees or memorize anything: you just go to the ritual and a few members do a dramatic reenactment that conveys some moral lesson. Some Lodges do all of the degree rituals in a single day. The Ballard Lodge schedules them as needed, and when I met Douglas, he was preparing to run the third degree ritual, devoted to Truth: “It takes about 30 minutes.” As a non-member, I couldn’t watch the ritual or even be told certain details about it, but Douglas assured me I could Google anything I might be curious about. I could even order Odd Fellow ritual garb online.

Non-Capitalist Enterprise

Douglas thinks there’s a bright future for Odd Fellowship, for the simple reason that capitalism is failing. Fraternal organizations are, in his words, “completely non-capitalist enterprises,” and the escalating crises of capitalism are only going to make such alternative modes of social organization more and more appealing to a wide range of people.

Douglas has, by his own account, “led a pretty nonstandard life,” and from the sounds of it so have the couple dozen people who are the core of the Ballard Lodge. That he and his fellow Lodge members control what I would guess is a $15-20 million dollar building in a hip area of Seattle is a pretty astonishing fact, and Douglas believes the dissonance between what’s happening at the Ballard Odd Fellows and what’s happening everywhere else in Seattle holds great promise.

Do you know Hakim Bey? He’s a very interesting Sufi anarchist. He developed this concept of temporary autonomous zones. One of the things that he said that really impacted me is that there’s a great power in people getting together for a non-commercial purpose, even if it’s just a quilting circle. A quilting circle in the current environment is a radical act. And us, we’re in this weird old building in a certain place that’s going in a different direction. And we’re trying to plant the seed of a social organization that’s very different from the shit that’s going on.

Douglas is an Odd Fellow through and through, but he’s a fan of fraternal organization more generally, and so is also a member of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Aerie just down the street. As a percentage of the population, Eagles’ membership is down, like every other fraternal organization, but for 60+ years it’s remained at about 800,000 members—a rather impressive achievement given the clear numerical decline of the Masons, Elks, Moose, and Odd Fellows.

Catie Beck is Worthy President of the Mother Aerie—the first Eagles group in the nation, founded in 1898. Her grandfather was in the Elks, and when she wanted to meet people and “get some grandparents in my life,” she too joined the Elks but found the experience lacking. The Eagles were more her speed; she joined the organization a decade ago and, at age 34, became Worthy President of the Aerie in 2017. A year later her partner, Jason, passed away.

It was sudden, surprising. I was sad, but everyone here knew I was sad. When you show up here, you don’t have to talk to people, but you’ll know people if you want to talk to them. If I wanted to not be home alone, I knew I could come in here. There’s always somebody here. They knew Jason, they cared about him, they pooled some money for me. It’s just a really good community.

Having grown up Catholic, Beck described it as a “church-type community but without the religion.” At the Eagles initiation (where you get a free drink), they do ask if you believe in a Supreme Being, but as Beck joked, “Diana Ross was in the Supremes, she’s a Supreme Being.” She’ll hear from time to time about how the appeal of the Eagles is that it’s a place to get “cheap, stiff drinks” (and the Eagles do embrace the self-description, “a drinking club with a charity problem”), but for Beck it’s much more than that.

$60/year to have a spot that always has seats. You could order your drink, and say, “Hey, I’m gonna go pick up my kid from school and close out later,” just that kind of environment. There’s always signs up there about PJ leaving a tab. You know, they’ll be back eventually. It’ll get settled at some point.

Douglas too lauded the Eagles for what they’ve built.

I started going to the Eagles when I traveled, there’s lots of Eagles all over rural Washington. And I dress like a Pakistani. If I’m not dressed like this, I look like something equally weird to people in eastern Washington. I’ve never been able to dress for the public very well. I gave up when I was about 40. But I can walk into any Eagles bar, anywhere in rural America, and I can say, “I’m an Eagle from Seattle,” and someone buys me a drink and everyone’s talking to me. That’s functional. To walk into a bar in any state of the Union and be adopted.

Belonging

Anyone reading this article could pretty easily become an Odd Fellow. Dues are $60/year. The rituals you need to go through to become a full-fledged member could all be done in a day. It’s not uncommon for small groups of friends to essentially take over a Lodge from an older generation. This is the dynamic that led to a white militia group taking over the Capitol Hill Odd Fellows, but it’s also played out in better ways. “It’s a common pattern that Lodges age out,” Douglas told me. “So a younger core moves in and takes over. Usually that’s a good thing.”

It’s been more than 20 years since Robert Putnam lamented the collapse of associational life in America in Bowling Alone, and yet today energized members of decimated fraternal organizations are quite hopeful. “The future of Odd Fellowship is unwritten,” said Rosenberg. Combine outright ownership over prime downtown real estate and with a willingness, nay, a desire to hang out with people you don’t know, and the results can still be quite inspiring. For a wide variety of reasons, Americans stopped being joiners, but remarkably there’s still plenty of opportunities to do so. Why “stand six steps back and promise you love me” when it could be “sit down and have a drink”?

One of the first things Douglas told me upon entering the Ballard temple was that the right hand signals would appease the Patriarchs Militant. The Patriarchs Militant are a subgroup of the Odd Fellows, a higher order that you can attain by going through further degree rituals. But since we were the only two people in the building at the time, I didn’t understand what he meant, and so at the end of the interview, I asked him about it.

“Oh, it’s the ghosts,” he said. Apparently it’s well-recognized that the ghosts of former Patriarchs Militant still hang about, as one might speculate they do at the former Capitol Hill temple. “You could call this a very haunted building. I actually do exorcisms. I did a complete cleansing of this building, which is something I do regularly. And usually it’s just opening a door. But the odd thing here, which is something I’ve never encountered before, is that there are a lot of people here who just seem to belong here. And I figured, they used to be members, who am I to say if they should be here or not.”

■

Benjamin Y. Fong is the author of Quick Fixes: Drugs in America from Prohibition to the 21st Century Binge (Verso, 2023) and the producer/host of Organize the Unorganized: The Rise of the CIO.